The word “whipping” in American history makes people think of a harsh and scary punishment from the past. It was a cruel thing to do that hurt a lot of people physically and emotionally.

Whipping is the act of hitting a person using particular tools such whips, rods, switches, the cat o’ nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, and so on.

During the early colonial period in America, whipping was a typical way to punish people. When the English colonists came to America, they brought with them a judicial system that included whipping as a way to punish wrongdoers.

People used it for a lot of different crimes, such as stealing, being intoxicated in public, and not following orders. The punishment was harsher or less harsh based on the crime and the laws in the area.

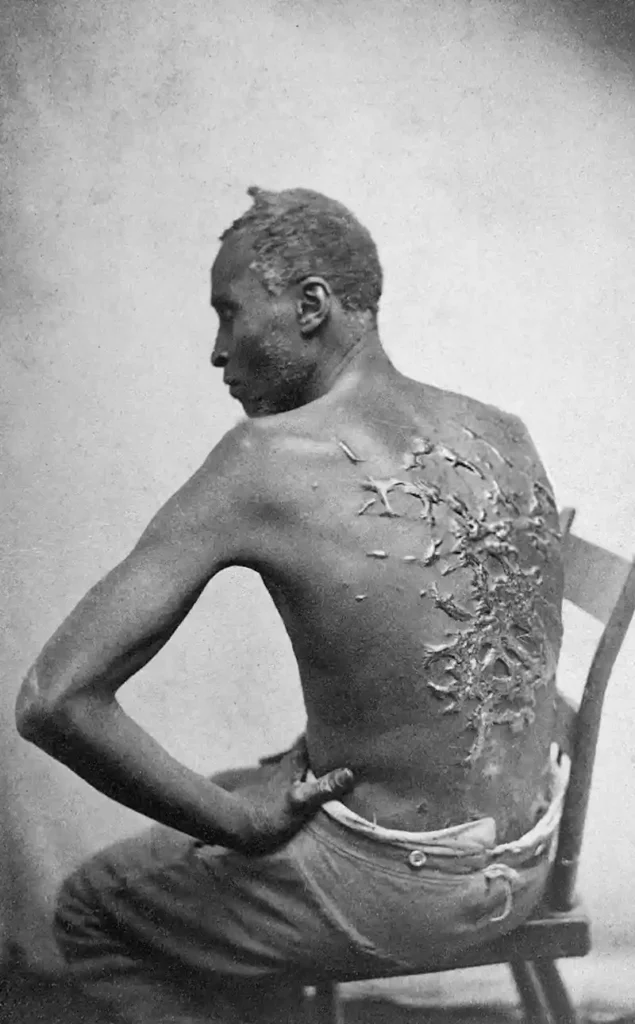

One of the most unsettling things about whipping in American history is that it was used a lot to control slaves.

People who were enslaved may be whipped brutally for even the smallest perceived mistakes or acts of defiance.

Whippings were not just a way to punish people physically; they were also a way to scare them mentally and keep them under control.

There were a lot of changes to the criminal justice system in the 19th century, such as moving away from corporal punishment.

Dorothea Dix and other important people pushed for better jails and better care of inmates.

Whipping as a public show slowly went out of style, but it was nevertheless practiced in some places, especially in the South, into the 20th century.

By the end of the 1800s, Maryland was the only state that still had a prohibition against flogging.

But Delaware joined it within a year, and in 1905, Oregon passed a similar law to Maryland’s, only to remove it six years later after a lot of public outcry.

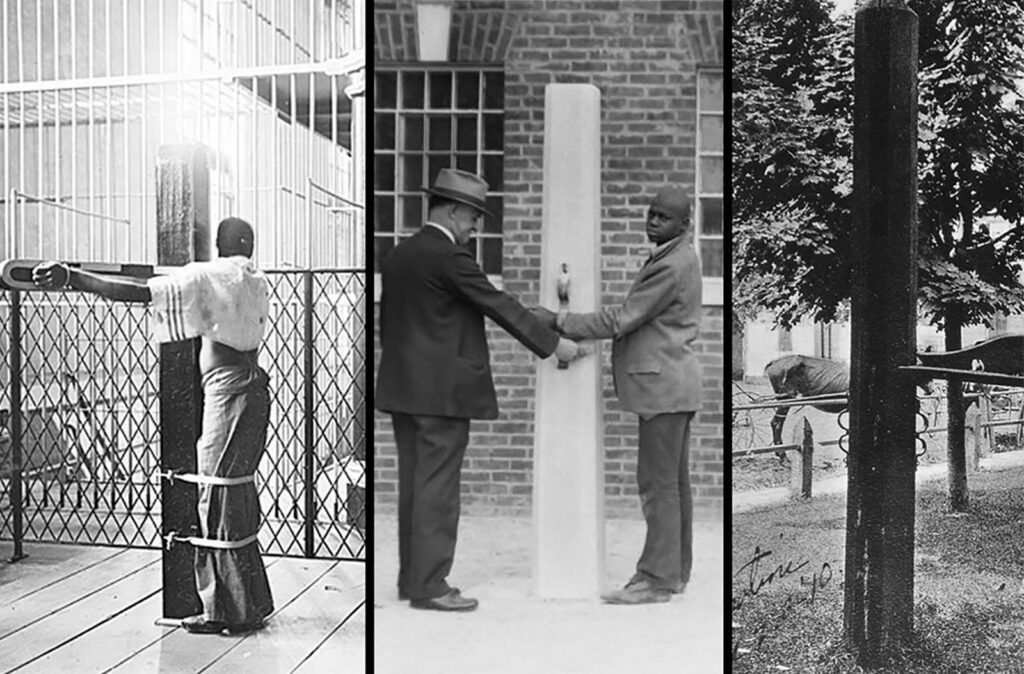

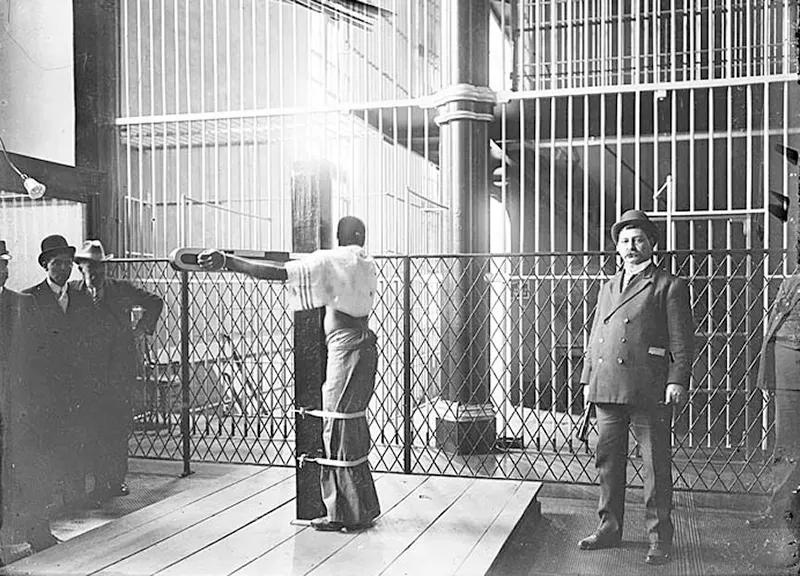

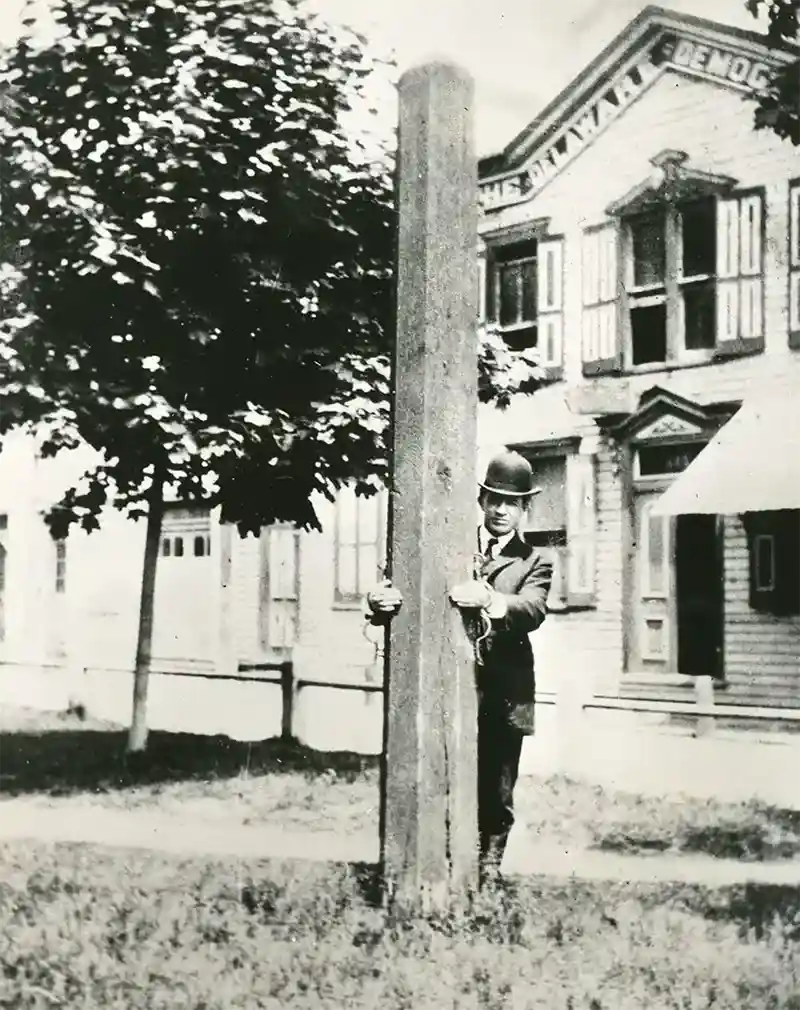

Baltimore’s Whipping Post

In the early 1900s, Baltimore was one of the few big American cities where flogging was still employed as a punishment by the courts.

This was primarily done in situations of assault and battery or other violent crimes.

In the Baltimore City Jail, a designated authority would whip people with a leather strap or whip.

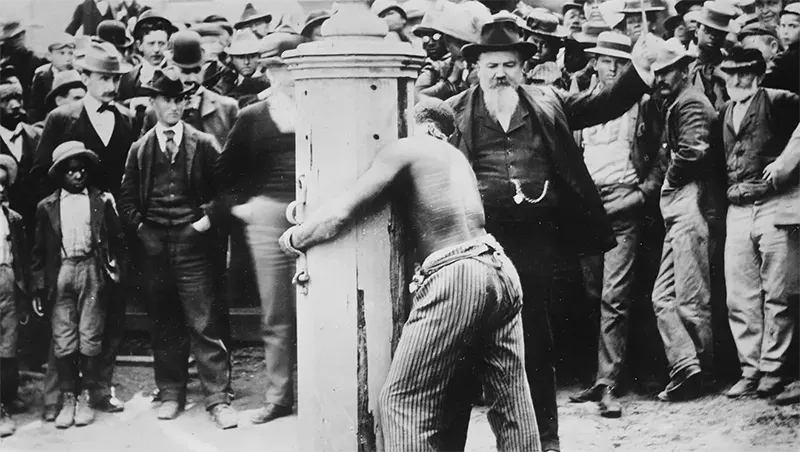

The picture above portrays a wife-beater who was found guilty and punished by being whipped. The Maryland Centre for History and Culture says that “on a cold March day, three blue-clad guards strapped Baltimore printer Clyde Miller to a cross-shaped wooden post in the Baltimore City Jail, arms outstretched and naked to the waist.”

Miller was beaten with a cat o’ nine tails, a whip with numerous knotted thongs, at a rate of one lash per second in front of 50 witnesses.

After the last strike, Miller was transported to the jail infirmary, where he cried, moaned, and “half-fainted from the pain.”

Sheriff Joe Deegan, who was in charge of carrying out the sentence, said afterwards that he didn’t enjoy the job but was “only the instrument of the law…” “[And] as long as that law is on the book, I have to follow it.”

This didn’t happen in Maryland in the 18th or 19th centuries; it happened in Baltimore in 1938.

Clyde Miller was the last person to be whipped on Baltimore’s old punishment system, which was based on a little-known 56-year-old legislation that said whipping was only for wife-beating.

Whipping in Baltimore got a lot of attention and sparked a lot of controversy.

People who didn’t like it said it was a cruel and old-fashioned way to punish people that went against the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment and the changing norms of human rights.

People who supported whipping, on the other hand, thought it stopped crime.

In the end, the practice of whipping in Baltimore was looked into and faced legal problems.

The criticism and legal pressure finally made the city stop using whipping as a punishment in the mid-1950s.

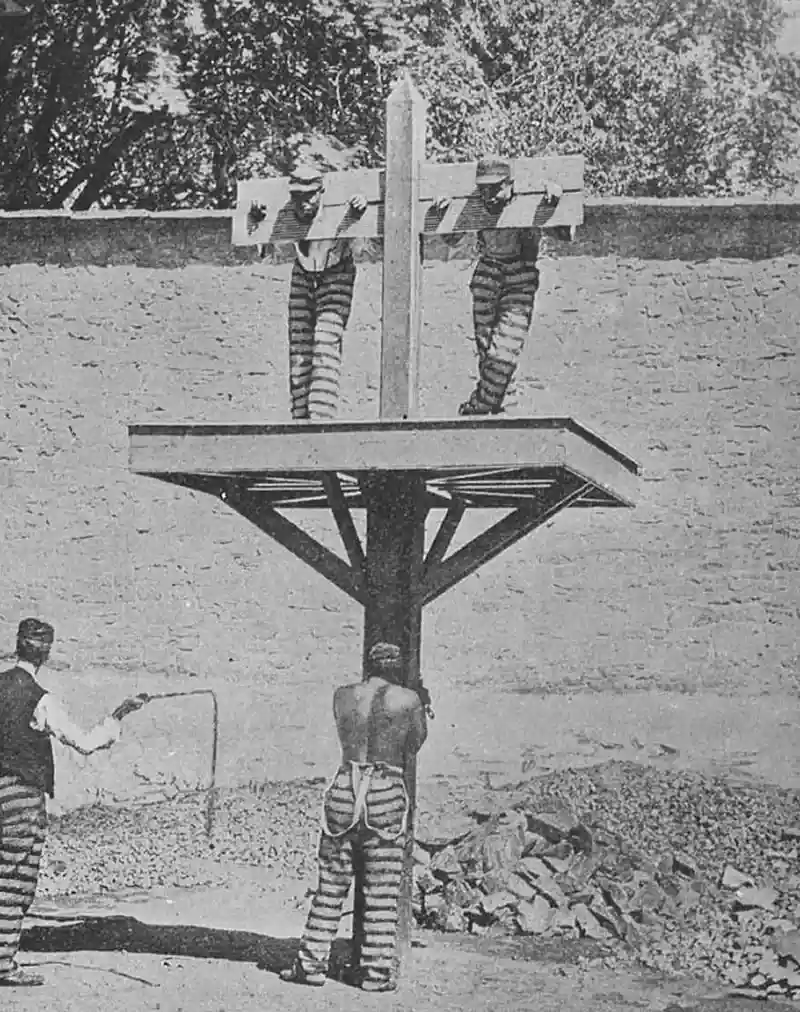

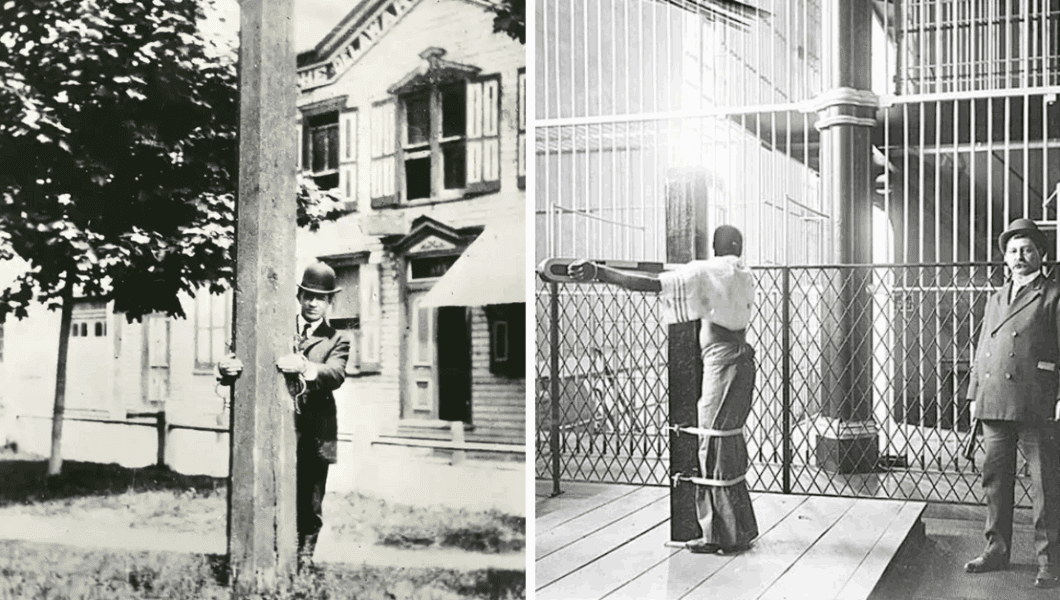

Whipping in Delaware

Delaware, like Maryland, had flogging as a punishment option long into the 20th century, especially in its prisons.

The number of lashes given would depend on how bad the crime was and what the jail authorities thought was best.

One historian thinks that between 1900 and 1940, more than 1,600 men may have been whipped in the state.

On one day in May 1904, sixteen men were punished on Delaware’s whipping post, which was known as “Red Hanna.”

The high numbers were possibly because Delaware had 24 crimes for which a guilty person might be punished by being whipped.

These offences included: a cashier, servant, or clerk stealing money; lying under oath or persuading someone to lie; deliberately and illegally exhibiting false lights to sink a ship; and breaking into a structure with explosives while someone is inside at night.

Also, breaking into a building at night with explosives when no one is home, and finally, bringing a stolen horse, donkey, or mule into the state and trying to sell it or actually selling it.

As prison reforms gained root and the goal of rehabilitating offenders became more important, the use of flogging as a punishment began to decrease down.

The legislation stayed in effect in Delaware until 1972, and the final whipping happened in 1952.

Other Old Photos of Whipping Punishment

Whipping in Military

The American Congress upped the legal limit on lashing for troops who were found guilty by courts-martial from 39 to 100 during the American Revolutionary War. In general, officers were not whipped.

As more people spoke out against flogging on US Navy ships and vessels, the Department of the Navy started requiring yearly reports on discipline, including flogging, in 1846. They also limited the number of lashes to 12.

According to reports, there were 5,036 instances of flogging on sixty navy ships during 1846 and 1847. Senator John P. Hale from New Hampshire pushed for the U.S. Congress to make flogging illegal on all U.S. ships in September 1850. This was part of a controversial addition to a navy appropriations measure at the time.

Hale got the idea from Herman Melville’s “novelized memoir” White Jacket, which had “vivid descriptions of flogging, a brutal part of naval discipline in the 19th century.”

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Maryland Center for History and Culture).

No Comments