England ruled as the unquestionably dominant superpower in Queen Victoria’s lifetime. London, its heartbeat, throbbed with the vitality of a busy city.

Towering buildings and magnificent palaces were evidence of the riches acquired from a huge colonial empire.

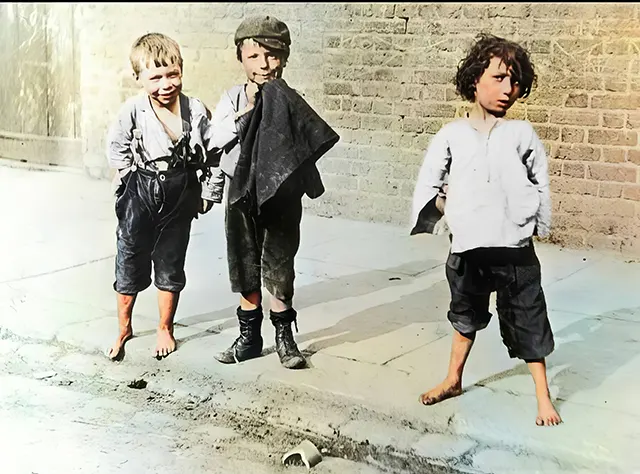

Beneft this bright surface, nevertheless, was a sober truth. A sharp contrast to the luxury above, poverty tore at the underbess of the city.

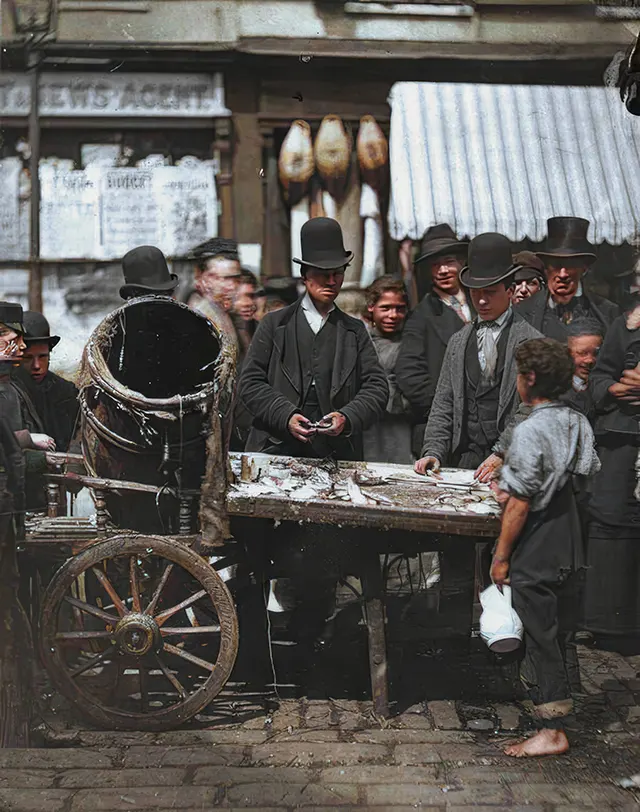

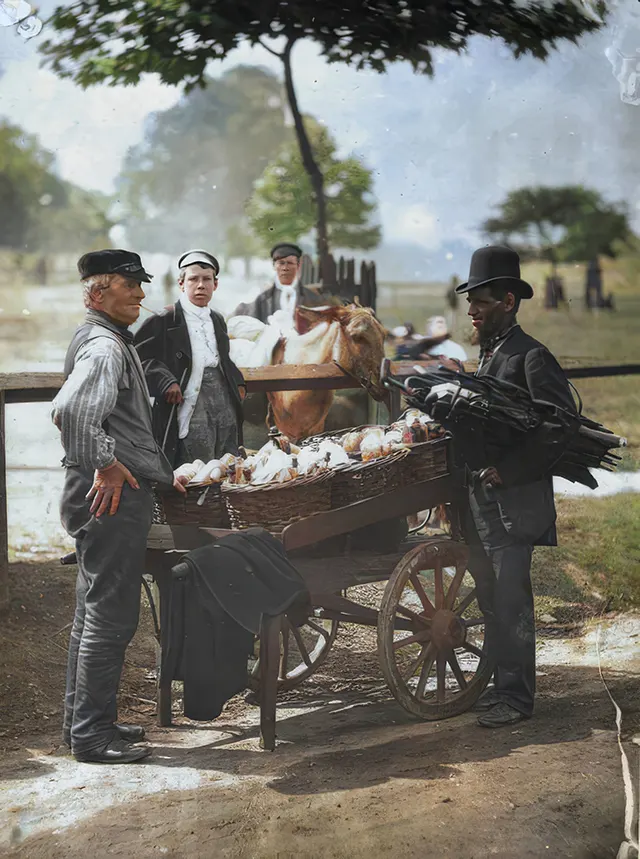

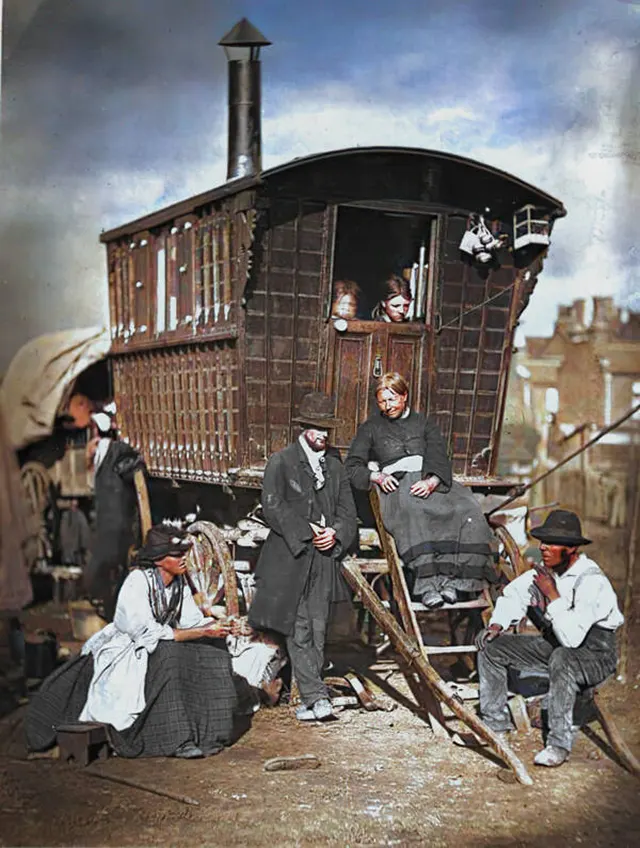

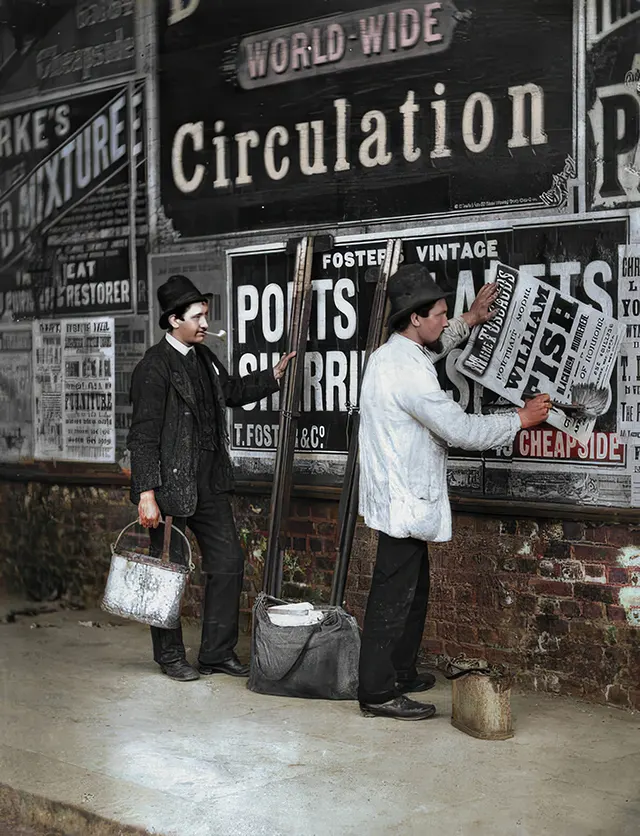

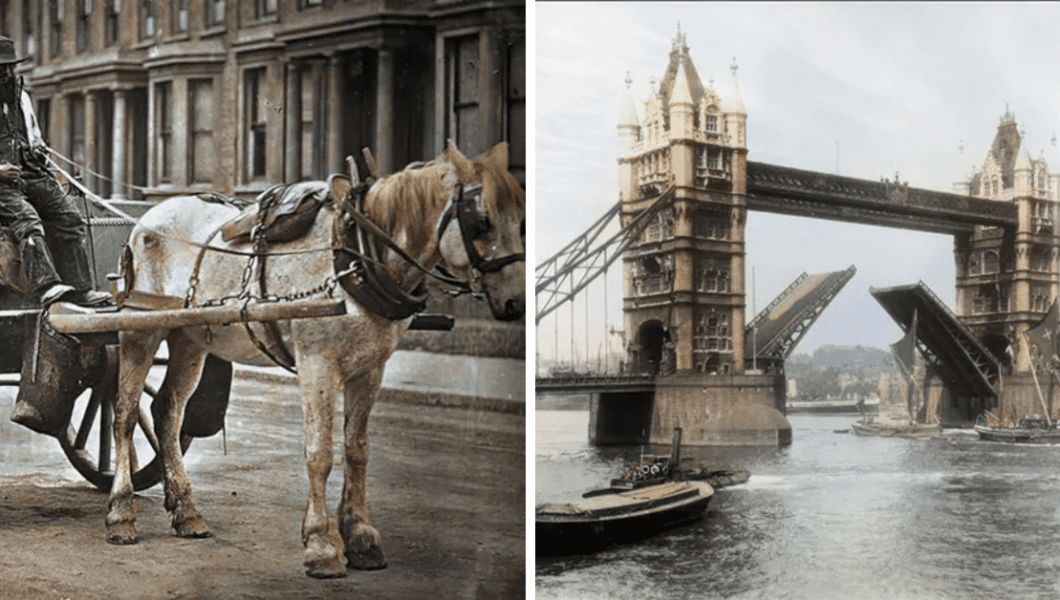

These amazing colourized images help to reveal this complex universe.

They provide a rare view into life at the end of the 19th and the turn of the 20th centuries, therefore transcending the boundaries of black and white.

From the famous, recently built Tower Bridge to the terrible hardships in London’s slums, these pictures reflect the whole range of Victorian life, flaws and all, including daily street scenes and the existence of ordinary people.

London changed during the 19th century to become the capital of the British Empire and the biggest city in the world.

From just over 1 million in 1801 to 5.567 million in 1891, the population surged.

Estimated at 6.292 million by 1897, “Greater London” comprised the Metropolitan Police District and the City of London.

London’s population by the 1860s was five times that of New York City, two-thirds bigger than Paris, and a quarter more than Beijing.

Unlike the ostentatious riches of London and Westminster, there existed a sizable underclass of extremely impoverished Londoners within a reasonable distance from the more wealthy regions.

Author George W. M. Reynolds noted the extreme income differences and suffering of London’s poorest in 1844:

“The most unrestrained prosperity is the neighbor of the most terrible poverty… For starving millions, the crumbs from the rich may seem appetizing, but yet these millions do not get them!

There are in that city five notable buildings: the church, where the devout worship; the gin-palace, where the impoverished seek to drown their griefs…

…the pawn-brokers, where pitiful creatures pledge their raiment and their children’s raiment, even unto the last rag, to get the means of purchasing food, and – sadly! too often – intoxicating drink

The workhouse, to which the impoverished, the aged, and the friendless hasten to lay down their aching heads – and die; the prison, where the victims of a vitiated condition of society expiate the crimes to which they have been drove by poverty and despair!

With its economy based on the Docklands and the polluting factories grouped around the Thames and the River Lea, London’s East End had always been a center for the working poor.

By the late 19th century, nevertheless, it had acquired an especially bad reputation for crime, congestion, extreme poverty, and depravity.

With a third of East End residents living in poverty, the 1881 census noted over a million people residing there.

American writer Jack London noted in his 1903 book “The People of the Abyss,” the shock of Londoners upon learning of his intention to visit the East End: many had never gone there although living in the same city.

He was advised to see the police rather than given a guide when he visited Thomas Cook & Son’s tourist office.

When he at last identified a reluctant cabbie to accompany him into Stepney, he said:

“While five minutes’ walk from nearly any location will bring one to a slum, nowhere in the streets of London may one escape the sight of wretched poverty; but the area my hansom was now penetrating was one interminable slum.

Short of stature, of dismal or beer-sodden aspect, the streets were teeming with a new and unusual race of people.

From each cross street and alley, we rolled across miles of bricks and squalor, flashing sweeping views of bricks and suffering.

Here and there lurched a drunk man or woman, and the air was filthy with jangling and squabbling.

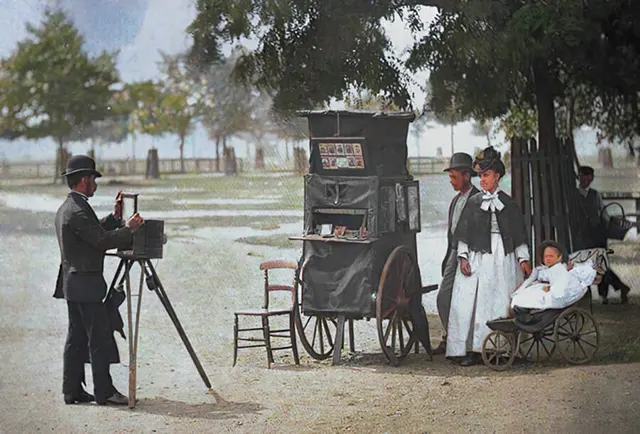

A street photographer snaps a family photo at Clapham Common

(Photo credit: Victorian London Street Life in Historic Photographs by John Thomson, Adolphe Smith 1994 / Colorized via DeepAI / Wikimedia Commons).

No Comments