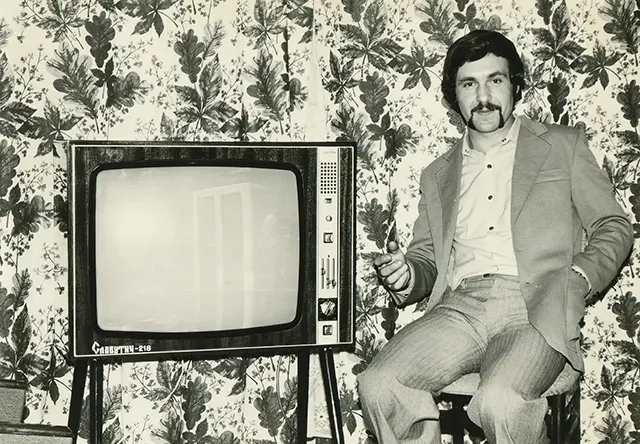

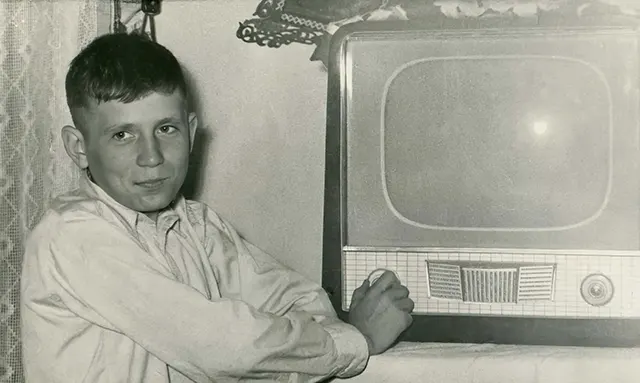

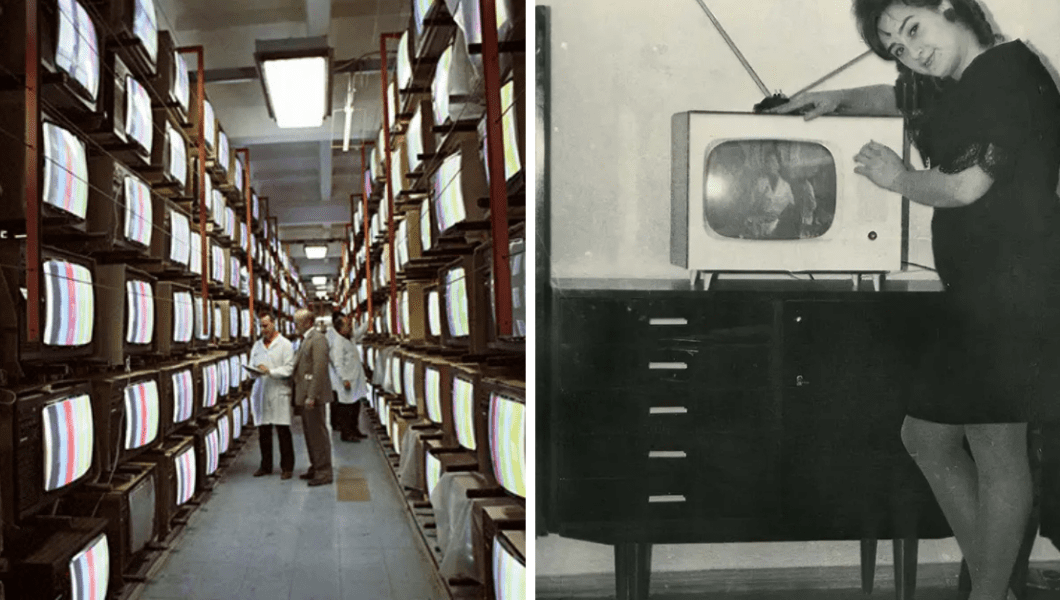

Once held in particular importance in Soviet society, television came to represent technological advancement and status.

Images from the post-World War II era via Perestroika show individuals proudly displaying their first TV sets, therefore expressing the enthusiasm and importance of this once-coveted item. These pictures provide a window into a time when for many families bringing a television home marked a turning point.

While the Soviet Union presented its own mechanical model in 1932, a mechanical device requiring connection to a radio for sound, television technology first surfaced in the United States in the late 1920s.

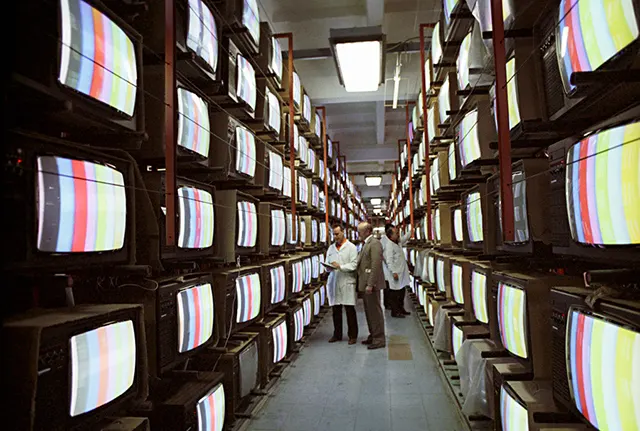

After World War II, mass production made televisions more available, therefore promoting widespread adoption.

Despite the expensive cost of 900 to 1,200 rubles, 61% of urban homes had a television by 1970; at a period when the typical monthly pay ran between 600 and 800 rubles.

Early Soviet televisions suffered frequent mechanical problems with displays no more than a postcard.

Programming was likewise limited; Moscow TV, the most active station in the nation, only ran four hours daily by late 1950s. Still, a New York Times writer observed early in 1954 that Muscovites were “frankly wild about television.”

Although most Soviet homes did not have a television until 1970, certain families bought sets far earlier regardless of their income level.

An American visitor was shocked in 1955 to find houses in ruins, sinking into the muck, yet still sporting television antennas.

Some cultural critics worried about the fast growth of television since they thought its impact may compromise Soviet values.

There were first arguments over how it affected viewers, but by the middle of the 1960s, as the novelty faded, the cultural elite mostly welcomed television’s arrival. Political officials, however, welcomed its ability as an effective propaganda tool.

Television had practically entered every Soviet home by the middle of the 1970s. Communist leaders considered it as a necessary tool for influencing public opinion, a truth that worried intellectuals who were dissident.

Believing Moscow’s tall Ostankino TV center shot propaganda straight into the heads of the public, many of them sarcastically referred to it as “the needle.”

Under close control, Soviet mass media guaranteed conformity with Party ideological guidelines.

From legislation controlling freedom of expression and outlawing “anti-Soviet agitation” to the thorough review process supervised by Glavlit, the main censorship authority, content was under several layers of legal and professional inspection.

Though many TV shows were first aired live, the turbulent political environment following 1968 resulted in more government control over editing and content development. Pre-recorded programming’s increasing popularity offered still another layer of protection against ideological errors.

Productions passed through several levels of verification before going on the radio, with severe penalties for those judged to have failed in their obligations. Negligent individuals could be disciplined, demoted, or even fired.

Like American PBS, Soviet television presented a wide spectrum of shows. News, instructional materials, documentaries, kids’ shows and sporadic films were among the broadcasts.

Live coverage of major athletic events including football and ice hockey games was common. Most programming came from other Warsaw Pact nations or was created here at home.

Tight self-censorship moulded Soviet television, with some subjects forbidden. Strongly forbidden were criticism of Soviet philosophy, erotica, nudity, too violent language, harsh language, and drug usage.

Presenters in news shows displayed perfect diction and a sophisticated mastery of the Russian tongue.

From 1970 until 1985, Sergey Georgyevich Lapin chairman of the USSR State Committee for Television and Radio set rigorous standards on presenters’ appearances.

Men were expected to dress in ties and coats; beards were off-limits. Pants were not let women wear. Lapin banned a close-up of Alla Pugacheva singing into the microphone since he thought it resembled oral sex.

Television became somewhat well-known despite these limitations quite quickly. From 1,673 in 1971 to 3,700 by 1985 daily broadcasting hours increased.

Built for the 1980 Moscow Olympics, PTRC—a modern television and radio complex—became one of the biggest facilities of its kind worldwide. The Ostankino Technical Centre in Moscow grew in prominence as well.

Late in the 1980s, Soviet television started to change. Western programming—mostly from Latin America and the United Kingdom—started showing up.

Often modelled after Western forms, talk shows and game shows were debuted. Soviet television had been completely devoid of advertising up to then.

The small number of businesses able to create commercials made them rare even when they were finally approved.

(Photo credit: TASS / VK / Enhanced and upscaled by RHP).

No Comments