The flight attendant occupation assumed permanent form in the 1930s as “women’s work,” that is, job characterized as embodying white, middle-class ideals of femininity but also mostly performed by women.

Together defining the new field of in-flight passenger service around the social ideal of the “hostess,” airline managers and stewardesses attempted to attract well-heeled travelers into the air.

Like middle-class, white women expected to treat guests in their own homes, a stewardess’s first responsibility was to mobilize the caring instincts and domestic abilities to serve passengers.

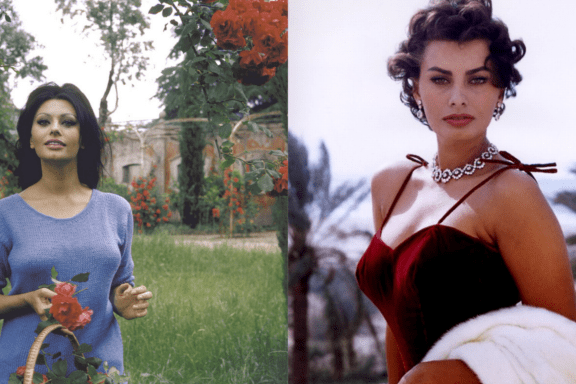

The early airlines’ crystallizing concept of the stewardess aloes demanded, however, was that the hostess must be as appealing as she was caring.

Stewardess work was limited from the beginning to white, young, single, thin, and beautiful women.

The girls who qualify for hostesses must be tiny; weight 100 to 118 pounds; height 5 feet to 5 feet 4 inches; age 20 to 26 years, per a 1936 New York Times story.

Add to that each must endure four times a year a rigorous physical checkup, and you are guaranteed the bloom corresponding with ideal health.

Millions of Americans began to fly on aircraft and the stewardess career grew as post-war II America underwent radical transformation.

Young working women might now enjoy fascinating lives, travel the globe, meet influential people, and not change bedpans or take dictation.

Originally paid well, prestigious, and adventurous, the stewardess post soon became the most sought-after career available to women in the country.

Airlines had their picture and could only hire the top crème de la crème as scores of deserving young women applied for every job.

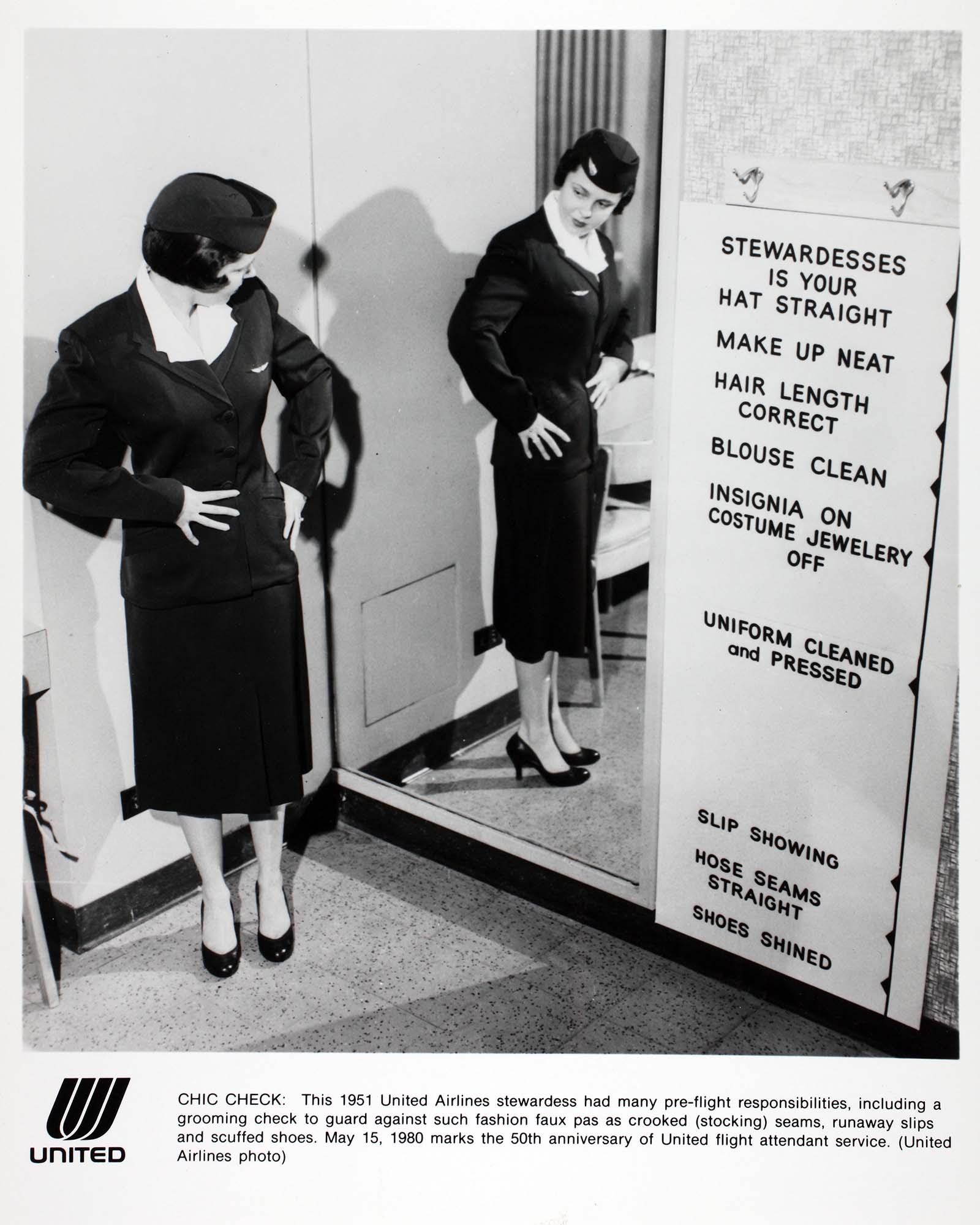

An applicant required to be young, pretty, single, well-groomed, slender, pleasant, intellectual, well educated, white, heterosexual, and doting to land a stewardess job.

Stated otherwise, the postwar stewardess represented the ideal lady of mainstream America.

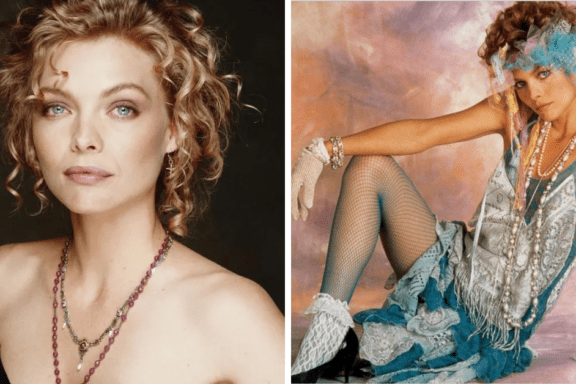

She evolved into an ambassador of felinity and the American way abroad as well as a role model for American girls.

One of the most crucial considerations for aspiring stewards was looks.

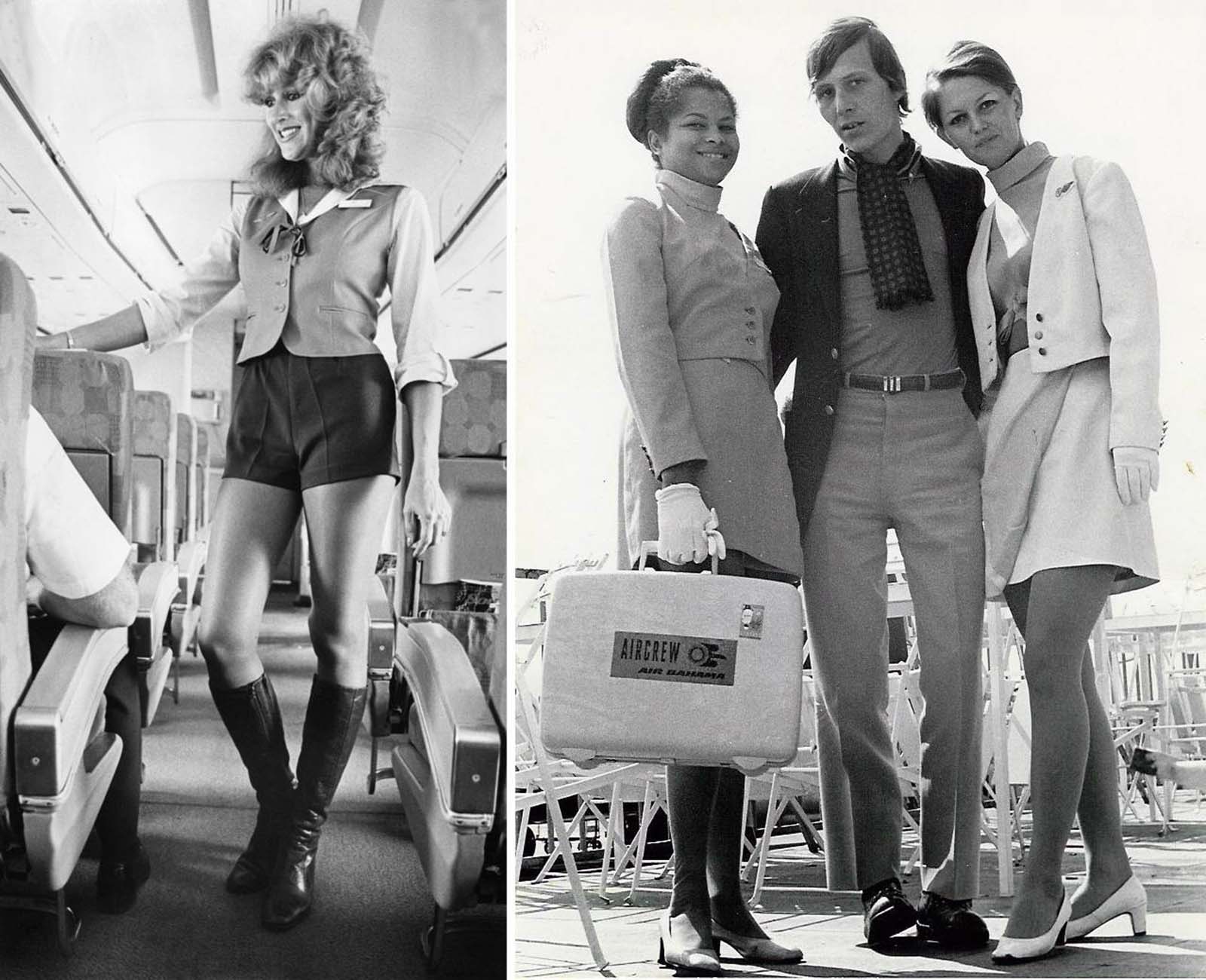

Airlines at the time thought that using female sexuality would boost their profitability; so, female flight attendants’ costumes were typically fitted and included white gloves and high heels.

They had to be single in the United States and would be let go should they choose to wed. A stewardess could not be pregnant. A stewardess could not go beyond her early thirty’s.

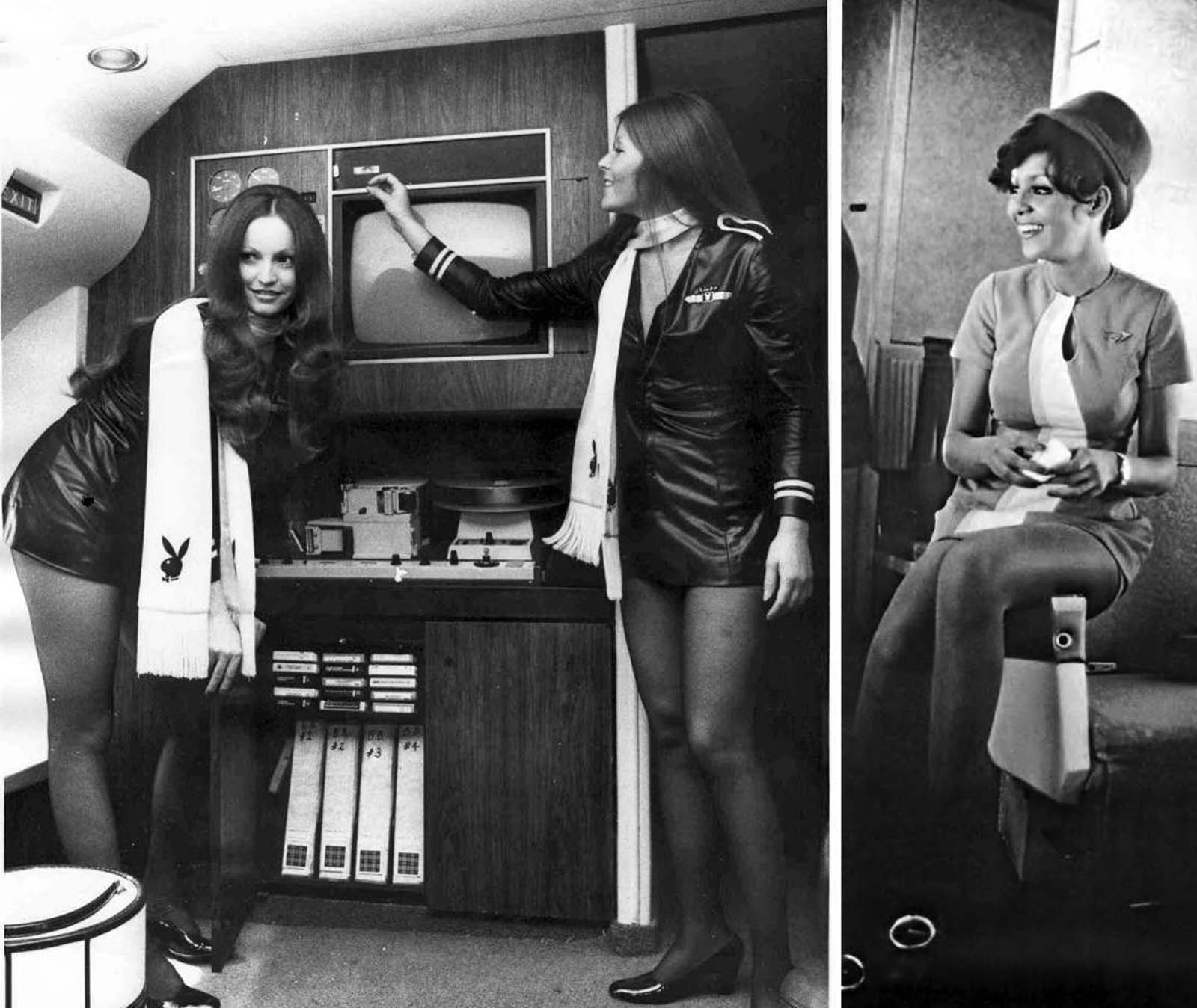

Big-named designers had a great time dressing them up and coming up with hot new gimmicks to promote air travel since no one tried to conceal the fact that flight attendants were there to be eye candy.

Jean Louis teamed a large, blocky kefi-type headgear with a basic, mod A-line dress with a broad stripe down the front and around the collar in 1968 for United Airlines stewardesses.

At its most sexualised, the stewardess image became a shared cultural vision that airlines blatantly pushed through their advertising.

According to Kathleen Barry’s Femininity in Flight: A History of Flight Attendants, the dark side of this stereotype was that women who attained this esteemed position were frequently harassed sexually by drunk passengers who might pinch, pat, and proposition the stewardesses while they worked.

Stewardesses were advocating changes inside the airline business, even if they served as both objects of sexual fantasy and mothering assistants.

Female flight attendants complaining about age discrimination, weight restrictions, and marriage bans were the first complainants of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Originally female flight attendants were fired if they surpassed weight restrictions, were required to be unmarried upon hire and fired if they were married, and depending on the airline, if they reached age 32 or 35.

Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the EEOC said in 1968 age limitations on flight attendants’ employment to be illegal sex discrimination.

At all airlines, the ban on hiring just women was repealed in 1971. By the 1980s, the no-marriage ban was dropped throughout US airlines.

Through lawsuits and agreements, the weight restrictions—the last such broad categorical discrimination—were loosened in the 1990s.

(Photo credit: SDASM Archives / The Life Picture Collection / San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives / The Jet Sex: Airline Stewardesses and the Making of an American Icon by Victoria Vantoch / Femininity in Flight: A History of Flight Attendants by Kathleen Barry).

No Comments