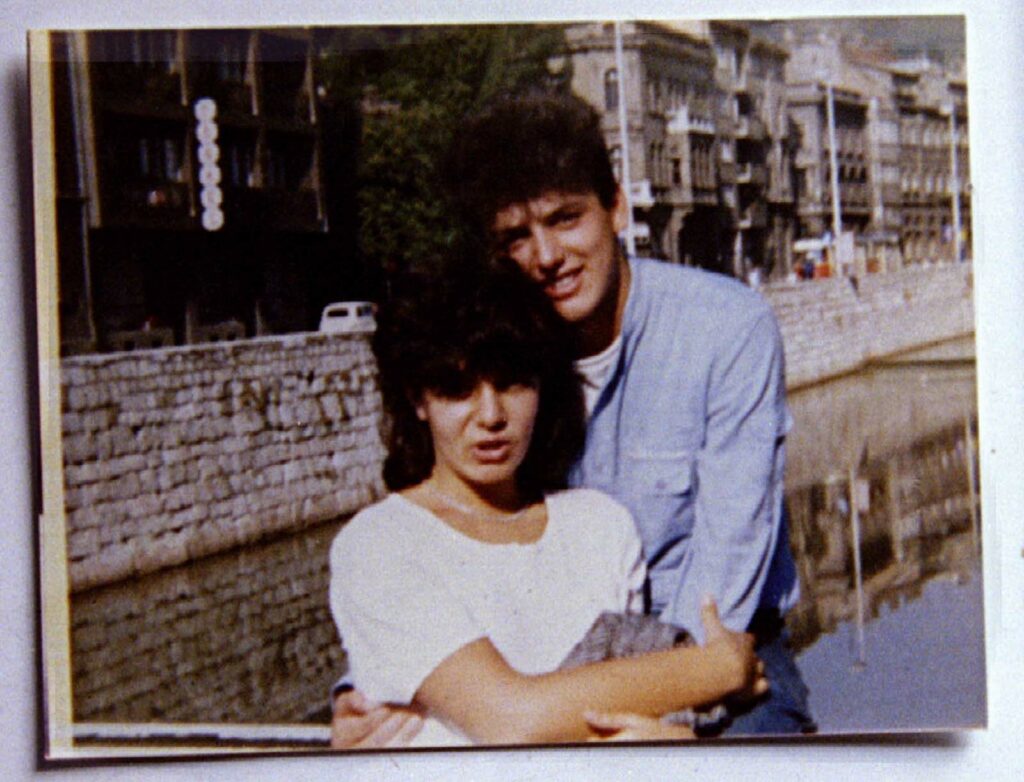

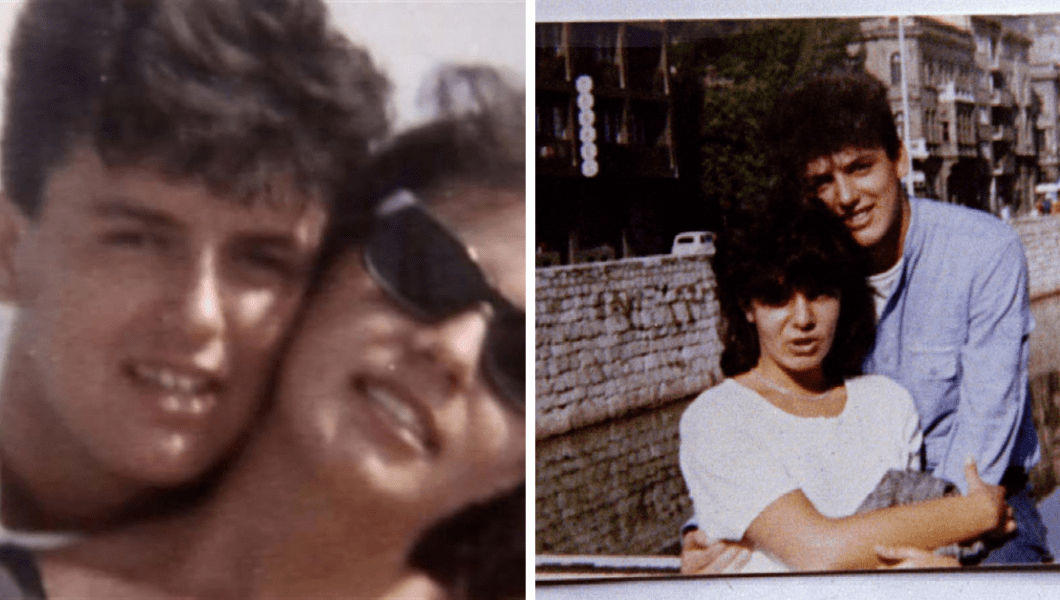

Few good things come out of war, and even the toughest of viewers from all sides of the fight is moved by the picture of the dead bodies of this young couple embracing on the street for days. The bodies of the childhood sweethearts lay in their last embrace for seven days, slain by bullets of snipers.

Still entangled, by the time they were eventually taken off Sarajevo’s Vrbanja Bridge, they had become emblems of enduring love caught in a pointless war. This is the Romeo and Juliet tale from Bosnia.

Part of Yugoslavia’s Wars, the Siege of Sarajevo (1992–1996) destroyed lives, families, and the future of many of the people. The narrative of childhood sweetheart Bosko Brkic and his nine-year girlfriend Admira Ismic is nothing less sad.

The fact that he was an Orthodox Christian or Bosnian Serb and she was a Bosniak Muslim distinguishes this love story. Among an ethnic war, the two 25-year-olds developed an unusual love in the centre.

Those who could flee did as the Siege got more harsher. Bosko’s father passed away; his family lived in Serbia. He could have left by himself. He stayed in Sarajevo with Admira until things become too difficult instead. Following one year of siege, the pair chose to flee to Bosko’s family.

Serbs from Bosnia enjoyed certain benefits. Muslims neglected. Gathering as much money as they could, they paid for their safe journey from Sarajevo to safety via Grbavica, the Serb-held area.

Named for the two anti-war activists who were the first casualties of the war on April 5, 1992, they would cross the Miljacka River via the Vrbanja Bridge, sometimes known as Sauda and Olga Bridge. Everyone agreed none would fire when they crossed the bridge at 5:00 p.m. on May 19, 1993.

Bosko and Admira were hopeful on that awful day. Dino Kapin, a Commander of a Croatian battalion affiliated at the time with Bosnian Army forces, said that about 17:00 hours a man and a woman were observed approaching the bridge.

A gunshot was heard as soon as they reached the foot of the bridge; all parties engaged in their passage claim that the bullet struck Boško Brkič and killed him right away.

Another shot was heard, and the woman shrieked, dropped injured but not dead. She died after crawling over to hug her boyfriend. She was clearly alive for at least fifteen minutes following the gunshot.

American photojournalist Mark H. Milstein, who created the eerie picture of Admira and Boško, stated in an interview that “the morning of May 19, 1993, had been pretty much a bust” for him as far as making pictures were concerned: “After lunch, I connected with a Washington Times writer and Japanese freelancing TV cameraman. We cruised the city together in search of something unique. Everywhere we went in Sarajevo, we arrived frustrated. Still, we opted to investigate the front-line surrounding the Vrbanja Bridge before calling it a day.

Bosnian forces were engaged in a little conflict firing at a gathering of Serb troops close to the Union Invest ruins. A Serb tank suddenly materialised 200 meters ahead of us and shot across our heads.

Hurrying to the next flat block, we discovered ourselves holed up with some Bosnian troops. One of the troops pointed at a small child and kid sprinting on the far side of the bridge and yelled at me to look out the window. Though it was too late, I grabbed my camera. Shot down were the boy and the girl. 25. Bosnian Admira Ismič and Bosnian Serb Boško Brkić both live.

It is not known with confidence who fired the rounds yet today. Days passed with the bodies of Admira and Boško laying on the bridge since no one ventured to retrieve them from the no man’s territory, Sniper Alley.

The Serbs and Bosnian troops debated over who killed the couple and who would finally bear responsibility as the remains rested on the bridge. Following eight days, Serb forces recovered the dead in the middle of the night and buried them in Lukavica.

Later on, nevertheless, it was discovered that the Serb army drove Bosnian POWs there in the middle of the night in order to retrieve the dead.

Following the end of the war, in 1996, Admira’s parents’ bones were moved to the cemetery Lav in Sarajevo and buried together on initiative and wish.

Although Brkic’s mother Radmilla described the couple as “a symbol of peace,” she objected to the analogy to Shakespeare’s masterwork. The two families always respected one another and their love was never outlawed. Bosko was greeted equally kindly by Admira’s parents.

Although her grandma was unsure that a mixed relationship might endure, the general reaction from both families captures the larger and historical picture of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

For 500 years, Sarajevo had been a cosmopolitan melting pot where Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Catholic, and Orthodox peoples coexisted at a crossroads of countries.

Many penned about them, songs, stories, articles, etc. Published by Reuters in May 1993, Kurt Shork’s piece among others is among the most well-known ones and has been across the globe.

A few years ago, Sarajevo’s group Zabranjeno Pusenje wrote a song called Bosko i Admira; also, Bil Maden under the name Bosko and Admira. Ismic and Brkic’s narrative reveals for many people living in contemporary Bosnia that only time will reveal if love or war will eventually prevail.

Picture credit: Reuters / Mark H. Milstein.

No Comments