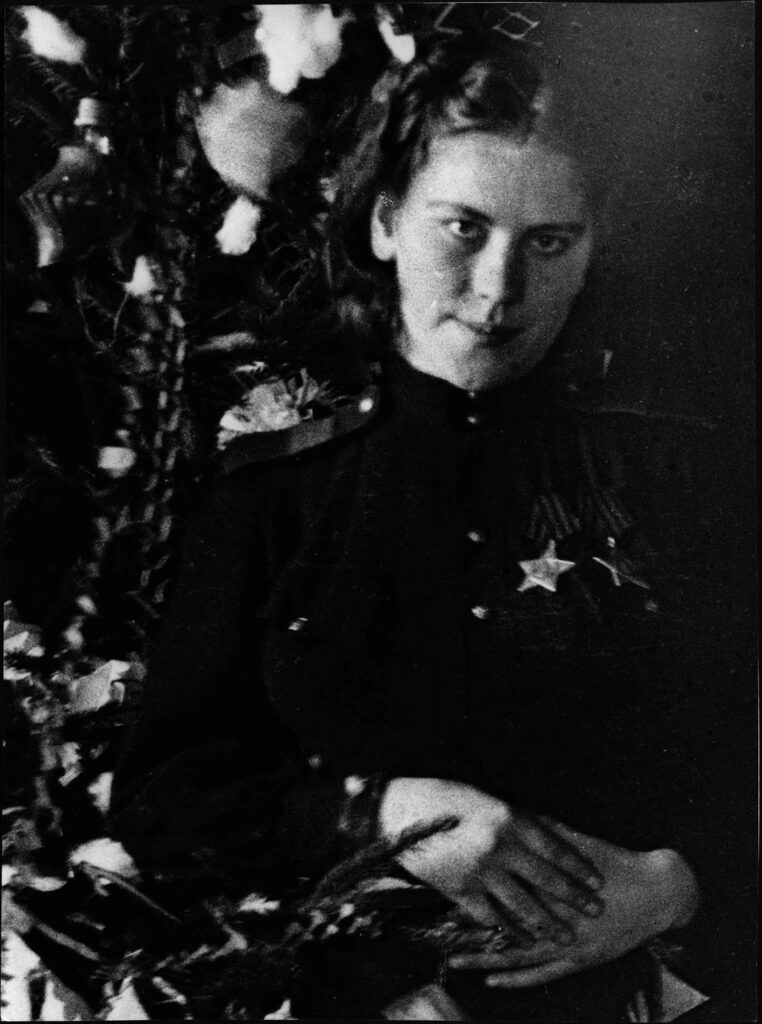

During World War II, Roza Shanina was a Soviet sniper who killed fifty-nine people, including twelve soldiers during the Battle of Vilnius.

Shanina joined the army after her brother died in 1941 and opted to be a marksman on the front line.

Praised for her shooting accuracy, Shanina was capable of precisely hitting enemy personnel and making doublets (two target hits by two rounds fired in quick succession).

A Canadian newspaper called Shanina “the unseen terror of East Prussia” in 1944. She was the first woman sniper in the Soviet Union to get the Order of Glory, and she was also the first woman in the 3rd Belorussian Front to get it.

Major Degtyarev, the commander of the 1138th Rifle Regiment, said in a report for the commendation list that Shanina killed 13 enemy soldiers between April 6 and 11 while being shot at by artillery and machine guns.

By May 1944, she had killed 17 verified enemy soldiers as a sniper, and Shanina was regarded as a brave and accurate soldier.

On June 9 of the same year, the Soviet daily Unichtozhim Vraga published a picture of Shanina on its top page.

It was decided to pull out female snipers when Operation Bagration started in the Vitebsk district on June 22, 1944.

They chose to keep helping the soldiers move forward, and even though the Soviets didn’t want to send snipers to the front line, Shanina asked to go.

She went nevertheless, even though her plea was turned down. Later, Shanina was punished for coming to the front line without permission, but she didn’t go to court-martial.

She wanted to join a battalion or a reconnaissance unit, so she went to Nikolai Krylov, the commander of the 5th Army. Shanina also wrote to Joseph Stalin twice with the same request.

The Germans tried to make the places they controlled stronger against the East Prussian Offensive, even if the odds were against them.

Shanina wrote in her diary on January 16, 1945, that even though she wanted to be in a safer place, something was pulling her to the front line.

In the same entry, she said she wasn’t scared and that she had even accepted to go “to a melee combat.” The next day, Shanina wrote a letter saying that she might be about to die because her unit had lost 72 of its 78 men.

In her last diary post, she said that the German bombardment had gotten so bad that the Soviet forces, including her, had to hide beneath self-propelled artillery.

Shanina was badly hurt on January 27 while protecting an injured artillery officer. Two troops found her with her chest ripped apart by a shell fragment and her stomach ripped open.

Shanina died the next day near the Richau estate, which eventually became the Soviet village of Telmanovka, even though everyone tried to save her.

A spreading pear tree on the shore of the Alle River (today called the Lava) was where Shanina was buried. Later, she was moved to Znamensk, Kaliningrad Oblast.

The Soviet press became interested in Shanina again in 1964–65, mostly because her diary was published. Shanina’s friends and family were requested by the publication Severny Komsomolets to write about what they knew about her.

Streets in Arkhangelsk, Shangaly, and Stroyevskoye are named after her, and there is a museum in the settlement of Yedma that is all about Shanina. There is a plaque at the local school where she went to school from 1931 to 1935.

War got in the way of Shanina’s personal life. “I can’t believe Misha Panarin is dead,” she wrote in her journal on October 10, 1944. What a kind person! [He] is dead… I knew he loved me, and I loved him too. I feel sad because I’m twenty and don’t have a close [guy] friend.

Shanina wrote in November 1944 that she “is flogging into her head that [she] loves” a man named Nikolai, even if he “doesn’t shine in upbringing and education.”

She also said in the same entry that she wasn’t thinking about getting married since “it’s not the time now.”

Later, she claimed that she “had it out” with Nikolai and “wrote him a note in the sense of but I’m given to the one and will love no other one.”

In her last diary entry, which was full of sad tones, Shanina wrote that she “cannot find a solace” today and is “of no use to anyone.”

(Photo credit: Russian National Archives).

No Comments