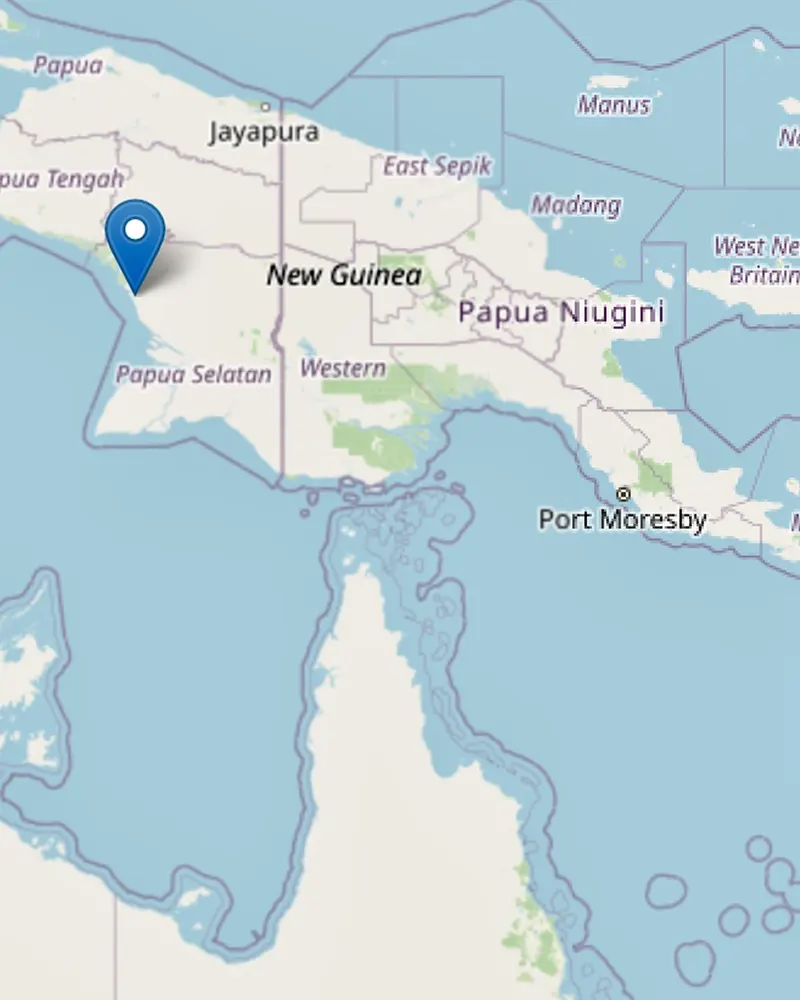

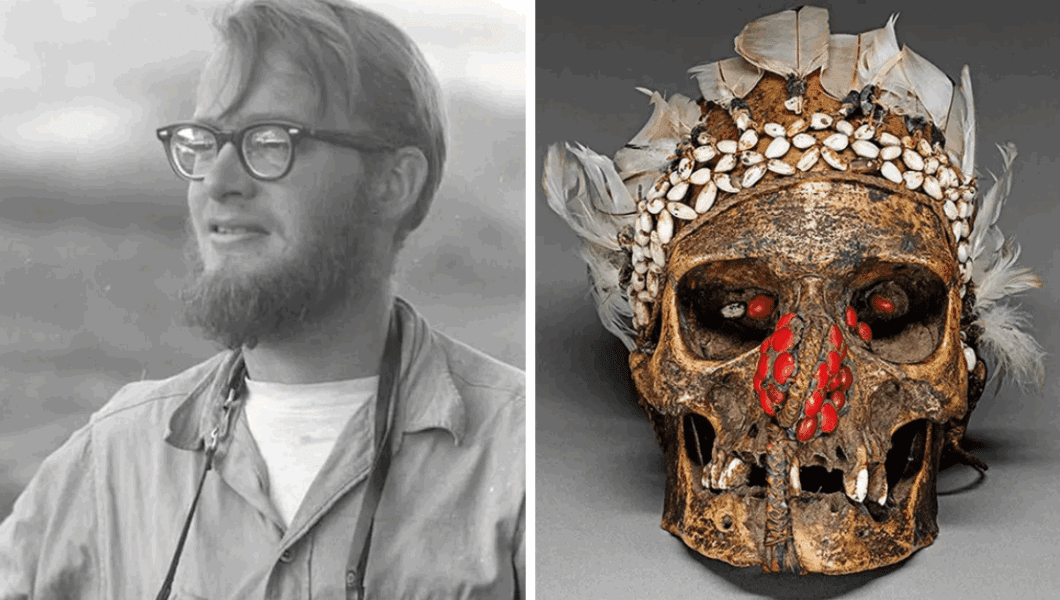

Michael Rockefeller, a promising young ethnographer, went missing in the southern coast of New Guinea in November 1961.

People were very interested in his disappearance, not just because he was the great-grandson of John D. Rockefeller, one of the richest men in history, but also because of the alarming rumors that came after.

He was officially reported dead by drowning, but over the years, a darker story has come to light.

People who have looked into the case, including investigators, journalists, and even missionaries, have found evidence that Rockefeller survived the wreck of his boat, made it to shore, and was slaughtered and devoured by members of the Asmat tribe.

The reality is still one of the most unsettling mysteries of the 20th century.

Michael Rockefeller’s Early Years

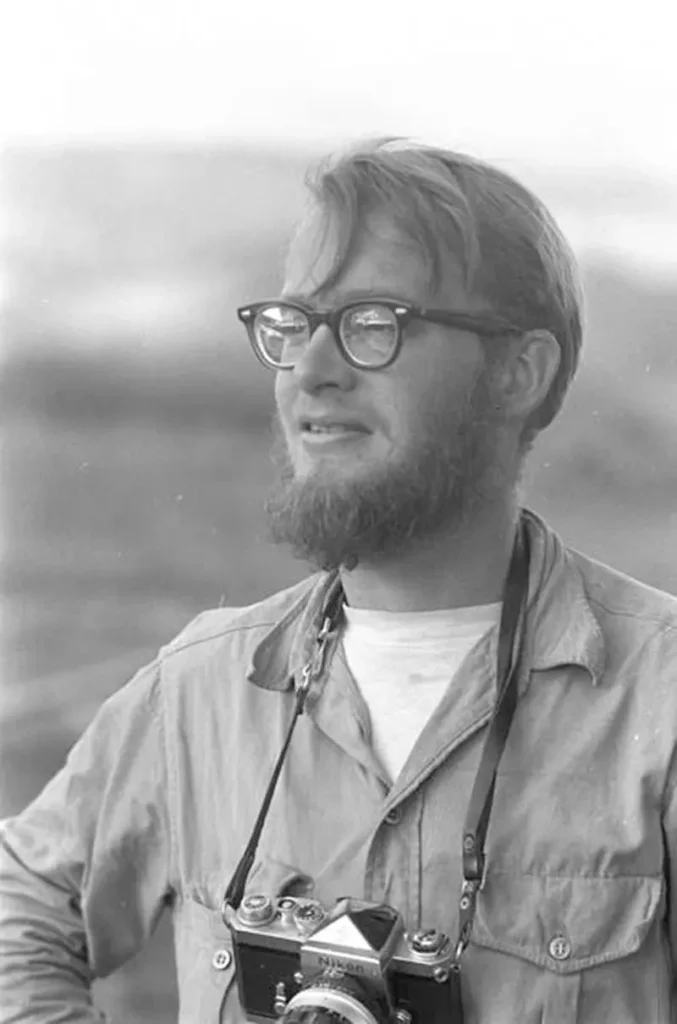

Michael Clark Rockefeller was born in 1938. He was the youngest son of Nelson Rockefeller, who was the governor of New York at the time, and he was a direct descendant of the famous businessman John D. Rockefeller.

Michael was raised in a wealthy household and was expected to take on a role in the family’s large political and economic network.

But from a young age, he showed a personality that was more interested in culture, art, and exploration than in power and money.

Michael didn’t want to spend his whole life in boardrooms when he graduated from Harvard University in 1960.

Instead, he was drawn to the art world, partly because of his father’s new Museum of Primitive Art.

He was attracted by the museum’s collection, which contained beautiful pieces from Nigeria, the Aztec Empire, and the Maya culture.

Michael joined the museum’s board and started to think about how he could help in a way that no one else could.

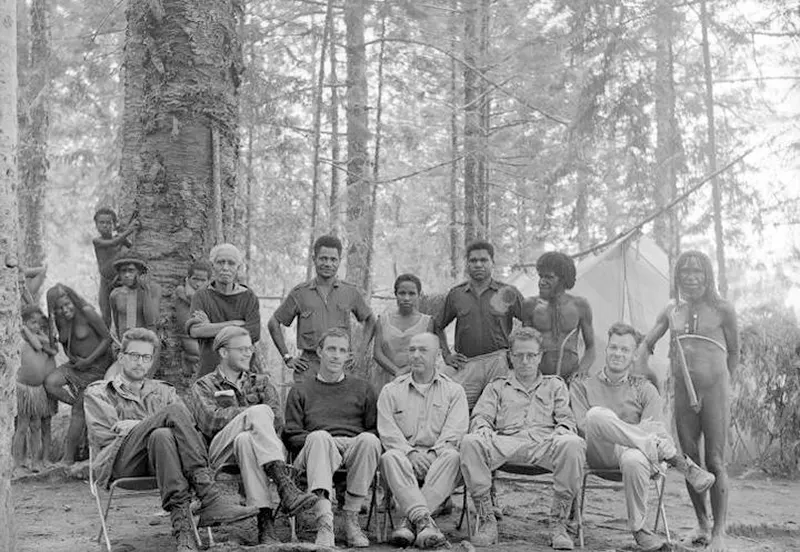

Karl Heider, a PhD student in anthropology at Harvard who collaborated with him, later remembered Michael’s goal of doing something no one had ever done before: collecting a large collection for New York from a culture that few outsiders had ever seen.

Michael had previously spent a long time in Japan and Venezuela, so he wanted to go somewhere even more remote.

Talking to people from the Dutch National Museum of Ethnology gave rise to a daring plan: to go to Dutch New Guinea to learn about the Asmat people and collect examples of their art.

The First Trip to Dutch New Guinea

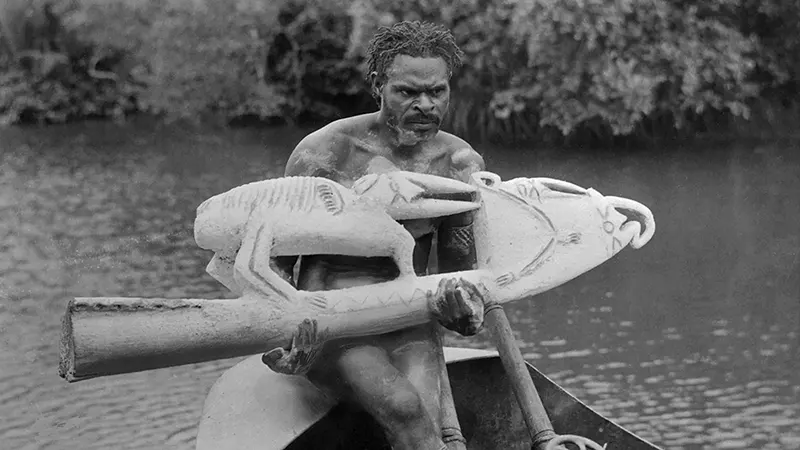

By the early 1960s, Dutch colonial officials and missionaries had made some progress in Asmat territory, but many communities had not been touched by outside forces.

The Asmat believed that spirits lived in faraway places and that pale-skinned people who came from across the sea were often seen as magical beings.

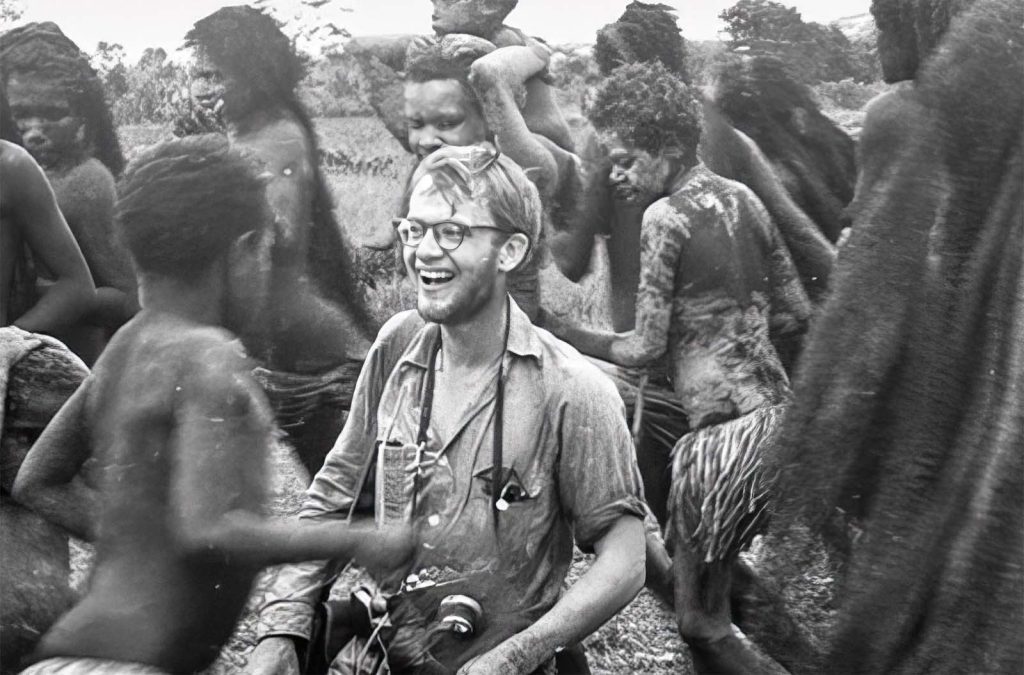

Michael and his little team went to Otsjanep, one of the bigger Asmat communities. The people there were okay with them, but they weren’t entirely welcomed.

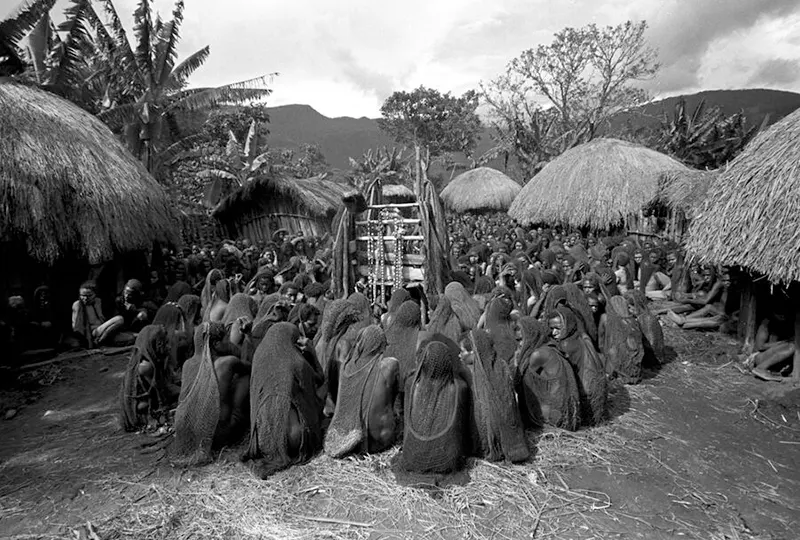

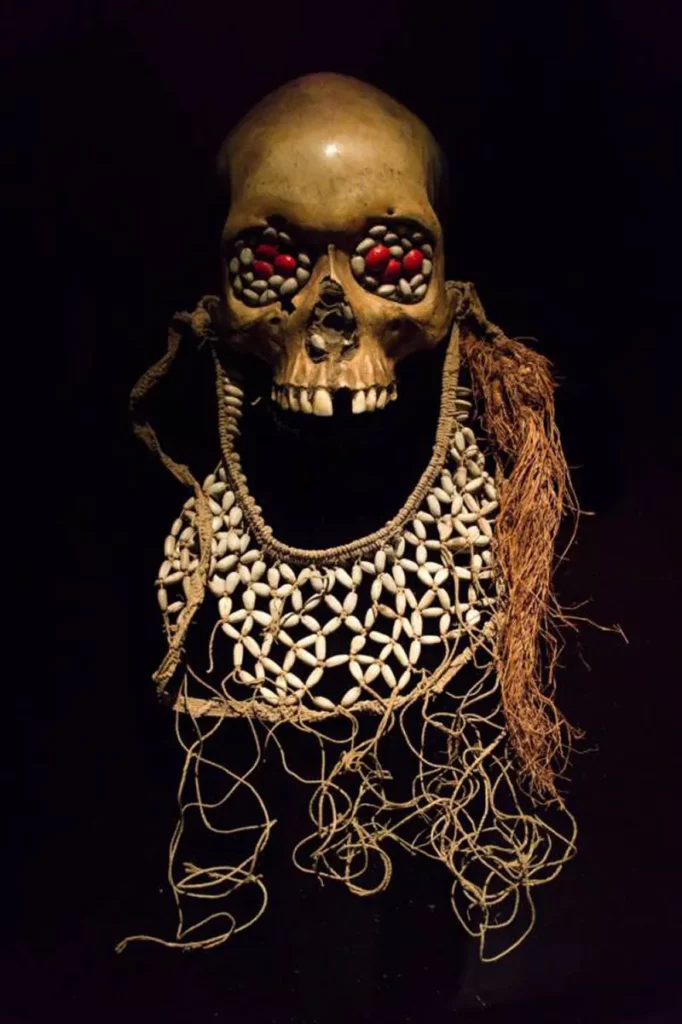

The villagers let people take pictures, but they wouldn’t give up treasured cultural items like bisj poles, which are finely carved wooden pillars used in religious ceremonies and headhunting rituals.

These rules didn’t appear to turn Michael away; instead, they seemed to make him even more interested. He saw the Asmat as a culture that didn’t follow Western rules and traditions, but instead had its own.

His diary writings from that time say that the area was more wild and distant than anything else he had ever seen.

People from outside the Asmat found their customs strange. Fighting between villages could be very violent. Sometimes, the winning warriors would cut off their adversaries’ heads, eat their flesh, and make weapons out of their bones.

Rituals included sexual rites that were new to Western culture and bonding ceremonies that required everyone drinking urine together.

Michael came back from the first voyage prepared to make a detailed anthropological record of the Asmat, along with a large collection of their art for the Museum of Primitive Art.

The Second Expedition and the Loss of Life

In late 1961, Michael set off for New Guinea again, this time with René Wassing, an anthropologist from the Dutch government.

They were going back to Otsjanep, where they intended to continue their investigation and get more relics for the museum.

On November 19, their little boat ran into bad weather out of nowhere. Strong winds and crosscurrents flipped the boat over, leaving Michael and Wassing hanging on to the hull that was upside down. They were around 12 miles from land.

Michael made a choice that would become renowned after spending hours in the ocean. He is said to have told Wassing, “I think I can make it,” before diving into the sea and swimming for land.

The next day, local men saved Wassing. But Michael was gone.

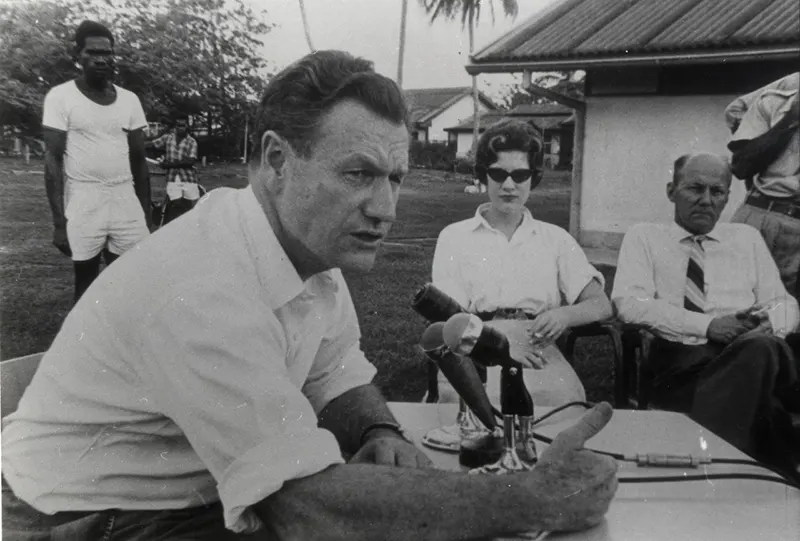

What happened next was an unparalleled search effort: ships, planes, and helicopters searched the area, and Nelson Rockefeller and his wife came to New Guinea to supervise the work. Even with all of this work, there was no sign of Michael.

Nine days into the hunt, the Dutch interior minister said there was no chance of finding him alive. The official cause of death was drowning, but no body was ever found.

The lack of closure led to a lot of speculation in the press, with possibilities ranging from shark attacks to people choosing to disappear into the jungle.

Testimonies and Ideas About a Violent End

People started to say that Michael had made it to shore in the months after he went missing, but that he had met a horrible end there.

Dutch missionaries who had lived in the area for years and spoke Asmat languages collected stories from people in Otsjanep.

These witnesses say that Michael was taken while he was only wearing his underwear. There was a fight about whether or not he should be spared, but he was eventually stabbed in the stomach and died somewhere else.

Witnesses informed Dutch minister Hubertus von Peij that roughly 15 guys split up Michael’s body parts, including his head, bones, and personal items like his shorts and glasses.

The first public word that Michael had been killed and cut up into pieces, with his bones used to make weapons and fishing tools, came out in March 1962.

A year later, Dutch police investigator Wim van de Waal looked into it and came to the same conclusion. He even found a skull that the Asmat said was Michael’s.

Milt Machlin, a journalist, looked into the case in 1969 and found evidence indicating Michael had been killed. He said that this matched with the Asmat’s traditional cycle of retribution warfare, where violence was often ritualized and used as a way to get back at someone.

Later Investigations and Scary Stories

Carl Hoffman, a journalist, looked into the mystery again more than fifty years after Michael Rockefeller went missing.

Hoffman wrote in his 2014 book Savage Harvest: A Tale of Cannibals, Colonialism, and Michael Rockefeller’s Tragic Quest for Primitive Art that the Dutch government had known the truth but kept it from the public to prevent political and cultural ramifications.

Hoffman had stories that were similar to those that missionaries heard decades ago. They said that Michael had made it to Otsjanep, where a group of men wanted to kill him as revenge for a violent event in 1958 between Dutch authorities and local warriors.

Michael’s head was cut off, his skull was split open so that his brain could be eaten, and the rest of his body was cooked and consumed.

They made daggers out of his thigh bones, spear points out of his tibias, and used his blood in ritual dances and sexual ceremonies to bring back spiritual balance.

Not long after, cholera broke out in the neighborhood, which many Asmat saw as a sign from God that they had killed someone.

The official record still doesn’t explain what happened to Michael Rockefeller.

The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art has many of the things he acquired, and the Peabody Museum has his photos from New Guinea.

But the unsettling thought that his life may have ended in ritual violence still hangs over his memory.

(Photo credit: As referenced / Wikimedia Commons / The Smithsonian Magazine).

No Comments