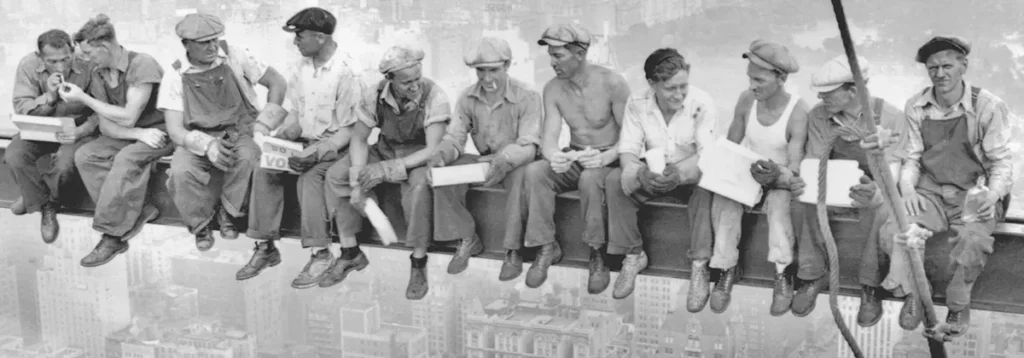

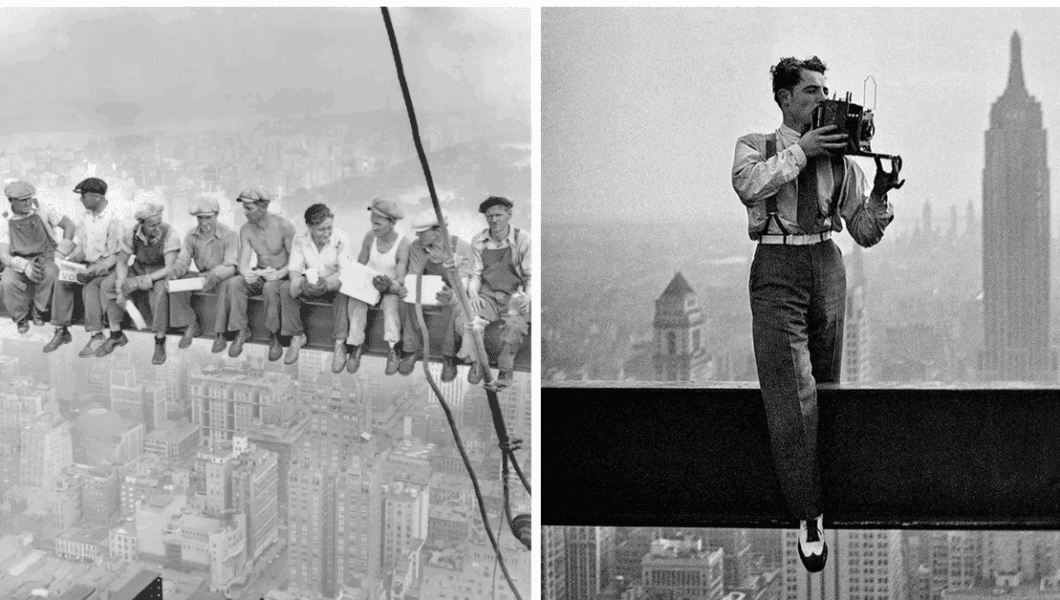

Taken on September 20, 1932, the classic picture known as “Lunch Atop a Skyscraper” catches a moment captured in time.

Eleven courageous ironworkers are shown in this black-and- white picture seated atop a steel beam, flying 850 feet (260 metres) over Manhattan, New York City.

Nestled inside the grandeur of Rockefeller Centre, their great elevation is the sixty-ninth floor of what was then the RCA Building, today known as 30 Rockefeller Plaza.

Designed as a PR ploy for a campaign advertising the building, this amazing snapshot—a triumph of both engineering and audacity—was set up.

The picture not only shows the splendour of the city below but also the friendship among these immigrant ironworkers who follow their midday ritual with a casual attitude even though their elevation is sudden.

Often navigating the complicated network of girders with casual familiarity, these guys, who seemed to defy gravity, wrote a unique chapter in the history of the city.

The Identity of the Ironworkers

A New York Post poll reveals a lot of assertions about the men’s identities in the image.

The 2012 documentary Men at Lunch looked at allegations that two of the men were Irish immigrants; the director stated in 2013 that he intended to check further on other allegations from Swedish relatives.

Cross-referencing with other images taken the same day, in which they were named at the time, the movie validates the identities of two men: Joseph Eckner, third from the left, and Joe Curtis, third from the right.

Identified as Slovak worker Gustáv (Gusti) Popovič, the first man from the right is carrying a bottle.

His estate turned up the picture, with the reverse inscription “Don’t you worry, my dear Mariška, as you can see I’m still with bottle.”

Ashley Cross, a New York Post correspondent, has referred to the image as the “most famous picture of a lunch break in New York history”. Many artistic creations have drawn on and reflected it.

Johnston referred to the picture as “a piece of American history,” even if many have written off it as a PR stunt.

Taken during the Great Depression, the picture became a symbol of New York City and has been repeatedly recreated by building workers. Time featured the picture in the 2016 ranking of the 100 most powerful photos.

Talking about the image’s relevance in 2012, Ken Johnston, manager of the Corbis historic collections, said: These people are so laid back about the discrepancy between the action – lunch – and the place – 800 feet in the air.

It’s visceral: I have heard folks say they find it difficult to view it out of height-related anxiety. And these men – their positions, attire, and attitudes help you to really perceive their personalities.

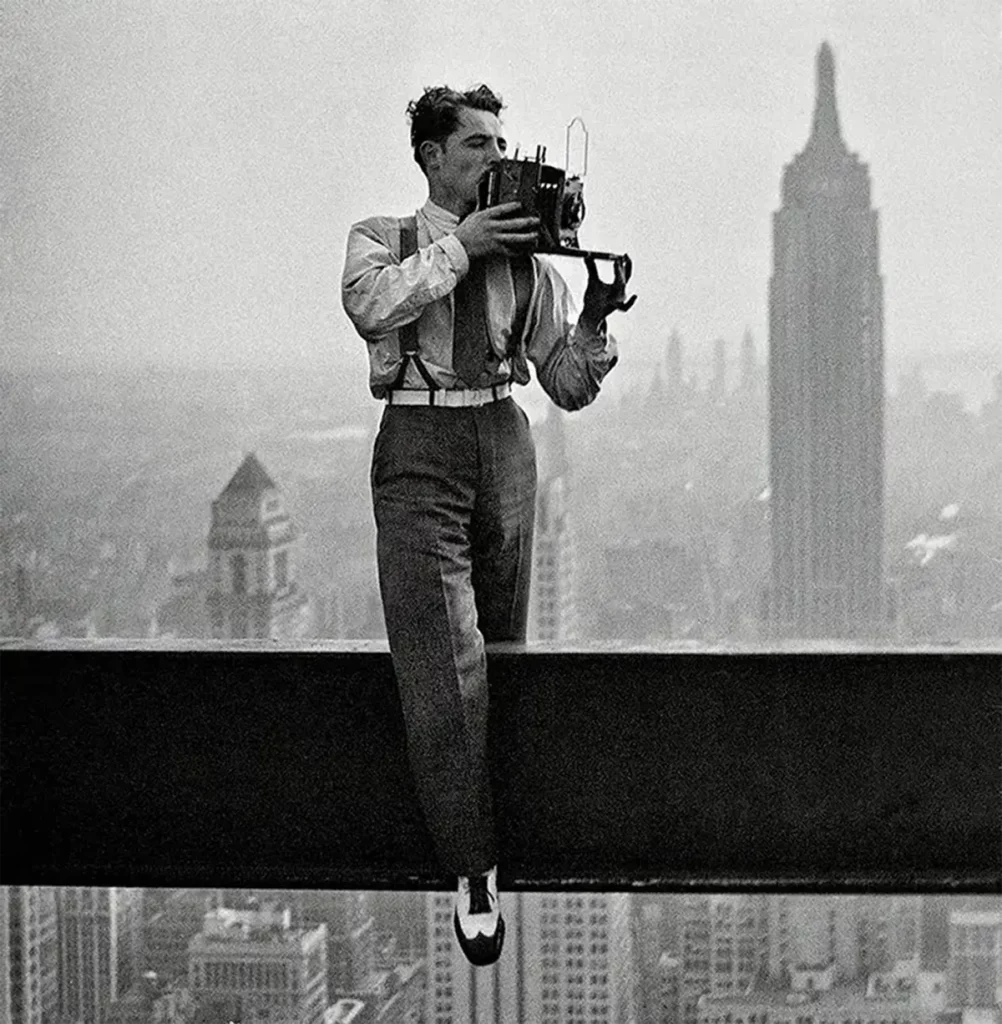

The “Lunch Atop A Skyscraper” Picture’s Photographer is Still a bit of a Mystery

The photographer is not known by name. Often misattributed to Lewis Hine, a Works Progress Administration photographer, on the erroneous presumption that the Empire State Building is the structure.

Living in Wilmington, North Carolina, Tami Ebbets Hahn observed a poster of the image in 1998 and assumed it belonged to her father, Charles C. Ebbets; 1905–1978. She wrote Ken Johnston of Corbis in 2003.

Professional photographers’ archive company, Corbis, engaged Marksmen Inc., a private investigator, to locate the photographer. An investigator came upon a The Washington Post item attributing the artwork to Hamilton Wright.

But the Wright family knew nothing about the picture. Wright was often credited for pictures taken by employees of his Hamilton Wright Features syndicate. Hahn’s father had worked for him.

In 1932, Ebbets had been appointed the photographic director of Rockefeller Center, responsible for publicizing the new skyscraper.

Hahn found her father’s paycheck of $1.50 per hour (equivalent to $32 per hour in 2022), the ironworkers photograph, and an image of her father with a camera, which appeared to be of the same place and time.

Analyzing the evidence, Johnston said: “As far as I’m concerned, he’s the photographer.” Corbis later acknowledged Ebbets’s authorship.

It was later discovered that photographers Thomas Kelley, William Leftwich, and Ebbets were present there on that day. Due to the uncertain identity of the photographer, the image is again without credit.

Ebbets was a daredevil himself; his biography describes his early years working as a stuntman in Hollywood and his mid-1920s acting performance as an African hunter known as “Wally Renny,” in multiple feature pictures. In addition, he worked as a hunter, auto racer, wrestler, pilot, “wing-walker.”

View images from Ebbets’s varied trip through life on a page designed by his daughter.

She has painstakingly maintained and restored his large photo collection with great love, enabling us to see the many facets of his success.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress).

No Comments