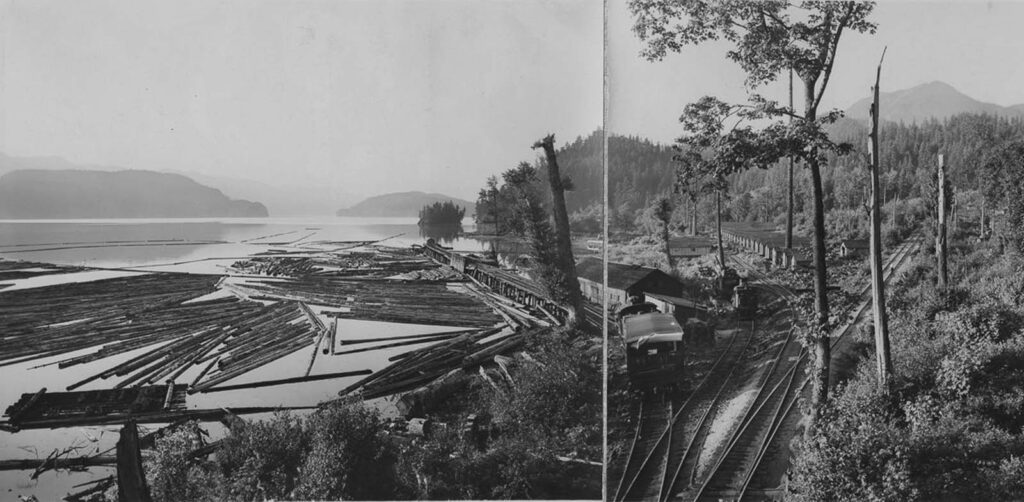

The completion of the Canadian Pacific Railroad in 1886 marked the beginning of the timber trade in British Columbia, it made possible the exploitation of the interior forests, presented the trade with the Prairie market, which was to sustain it until 1913 and it attracted plentiful capital to the industry for the first time.

For it opened the industry the Atlantic, particularly the shoreline of the United States and the significant United Kingdom market, the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914 marked the third phase of the trade’s history.

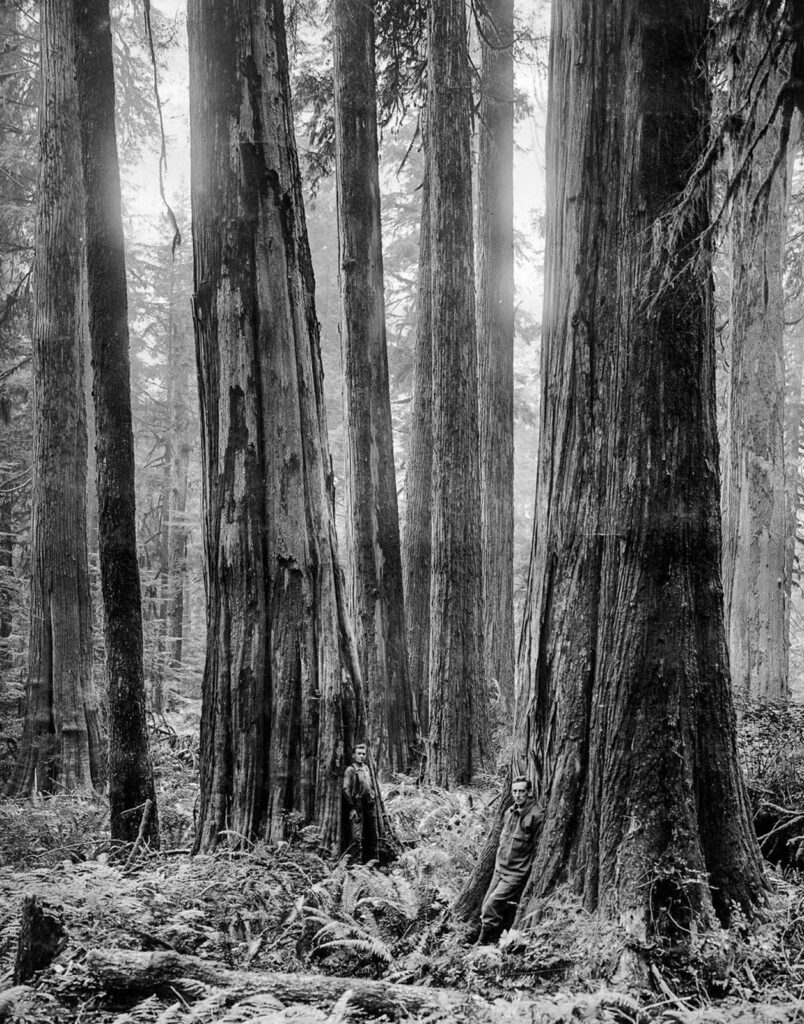

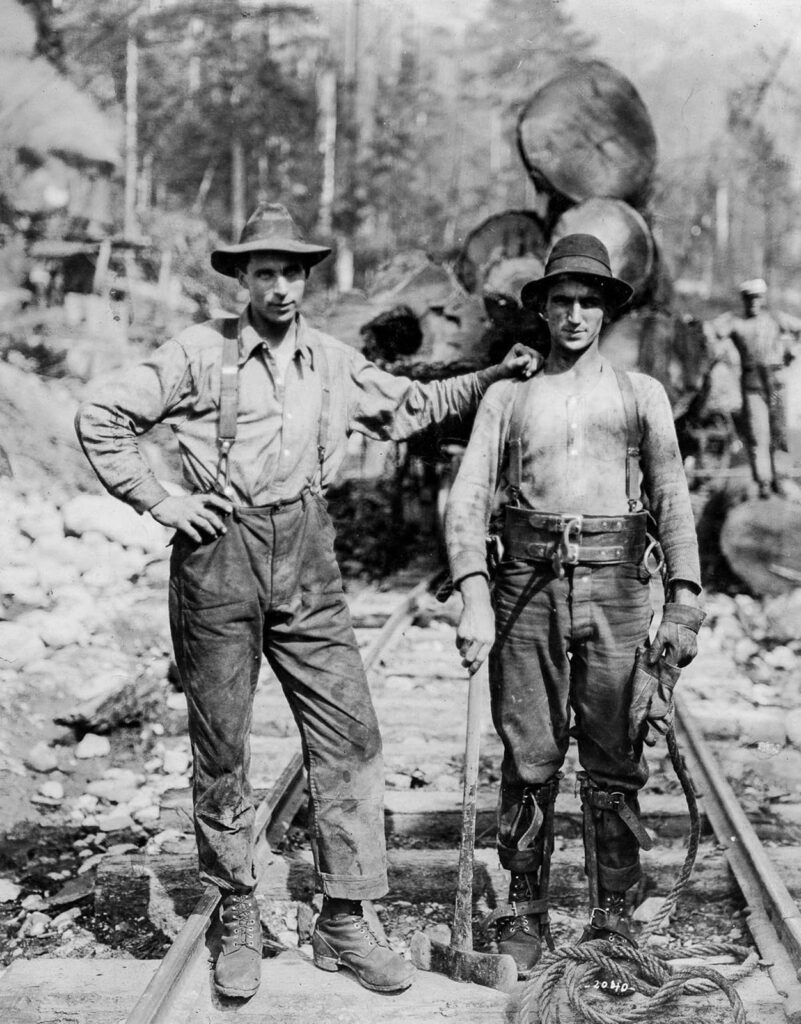

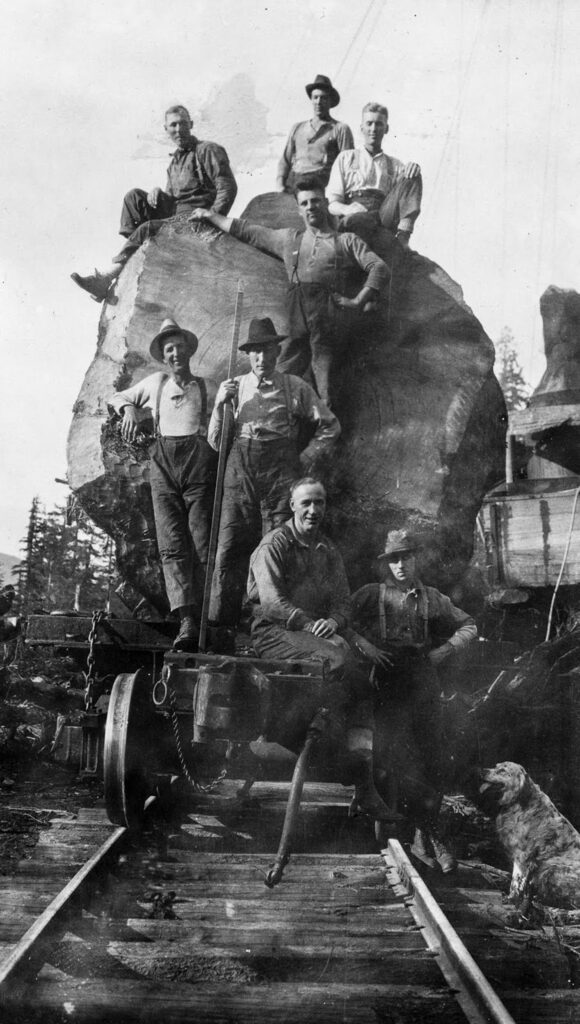

The area was appealing for ships’ masts and other timber products despite the tough and challenging terrain because of the profusion of tall cedar and Douglas Fir trees. While in the west skid roads had to be created out of wood, in the colder eastern woodlands falling logs could be skidded down snowy roadways.

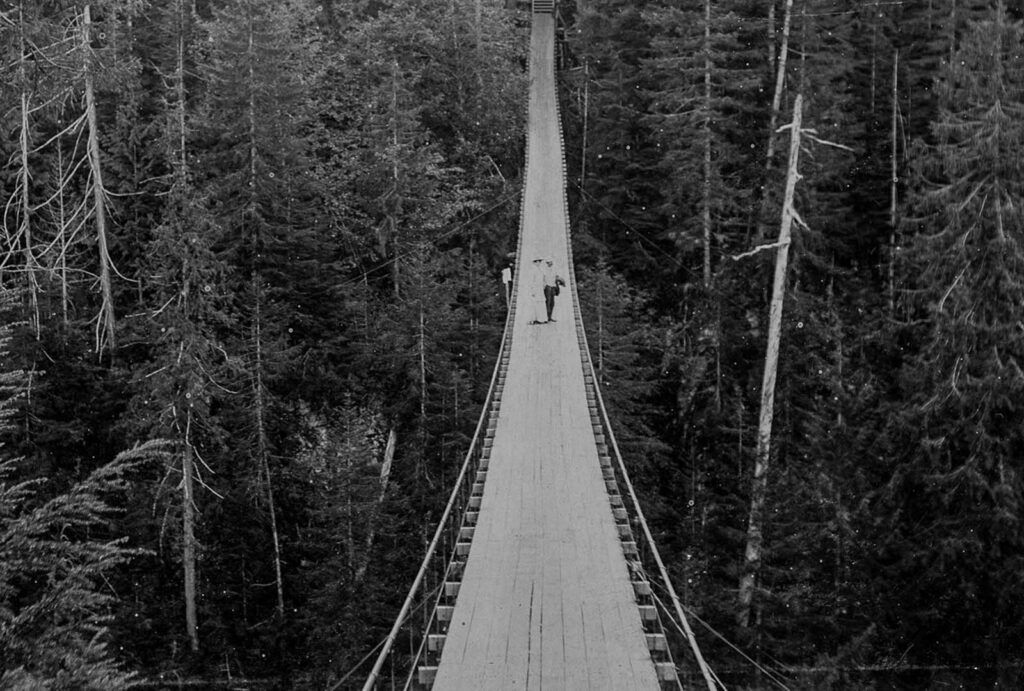

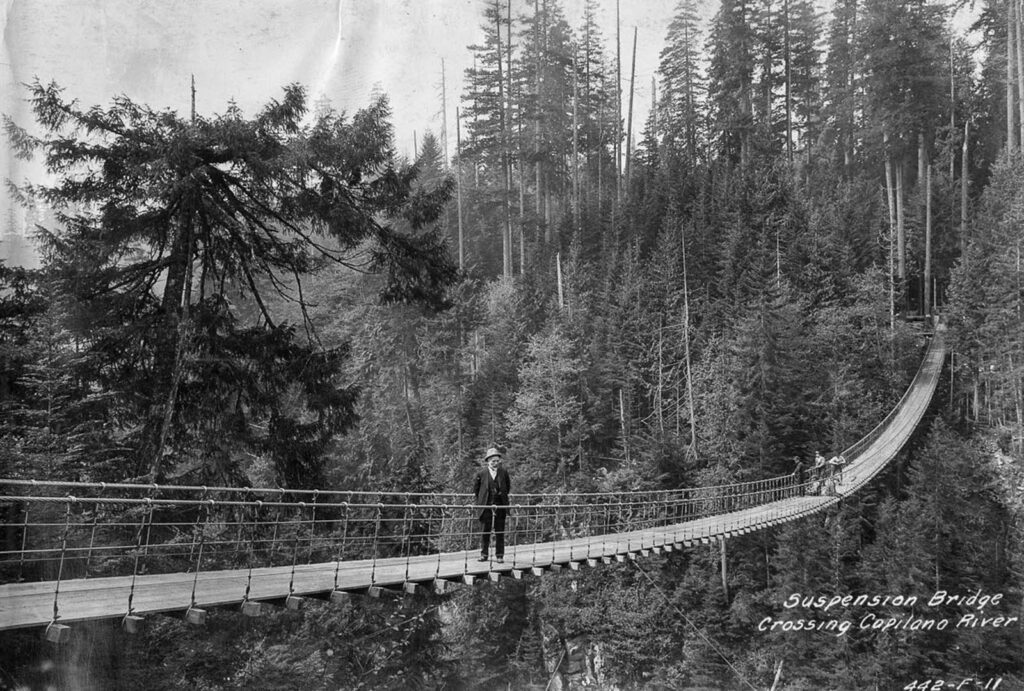

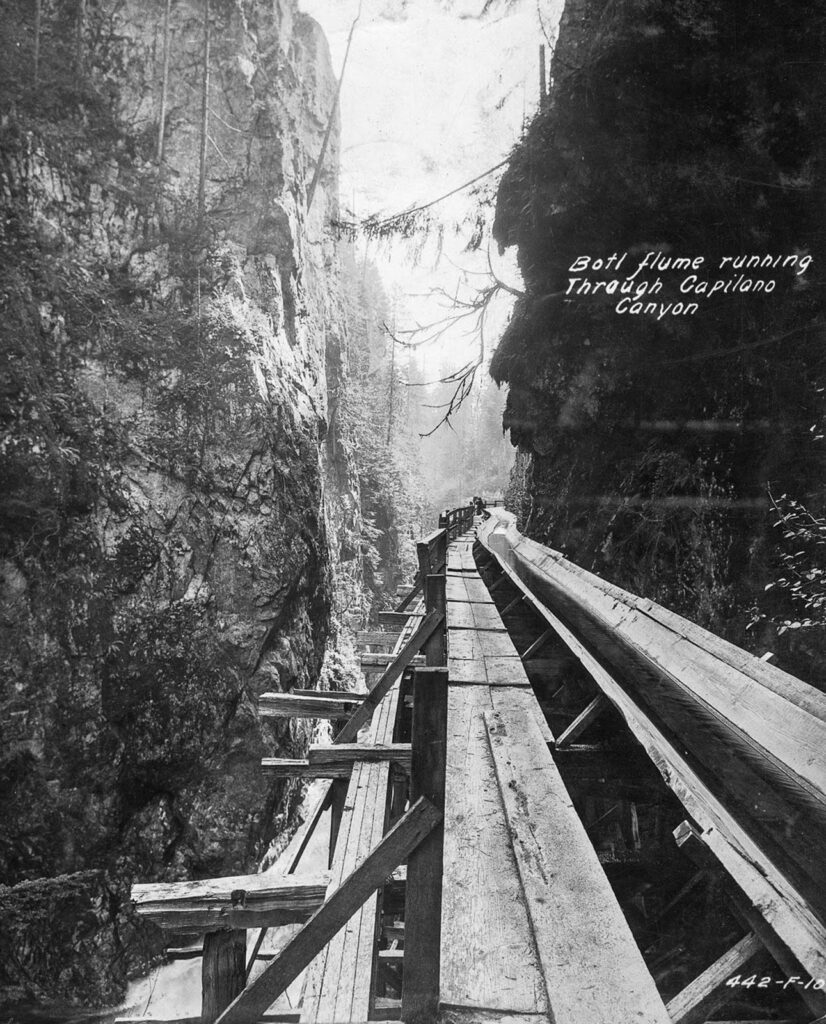

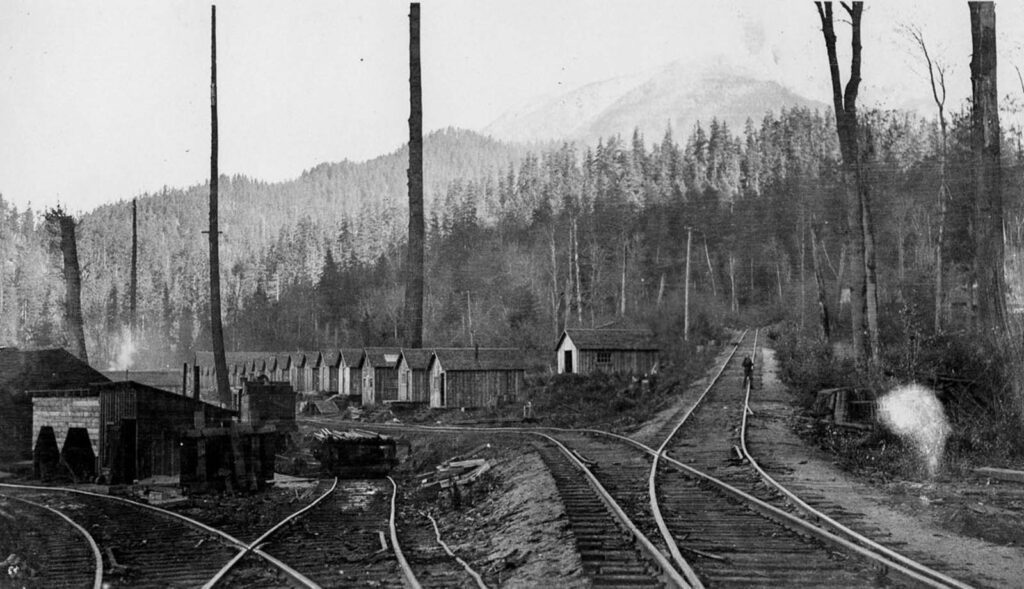

From the mountains, oxen, trucks, skids, flumes, and railroads spanning canyons carried trees down to the water on newly constructed trestle bridges. Half of Canada’s annual timber production by 1930 came from British Columbia.

After 1940, the timber trade followed still another trend. War-time shipping challenges, followed by a seemingly permanent dollar scarcity in the sterling region, essentially reduced the relevance of the United Kingdom during a sustained era of prosperity in the United States; nevertheless, helped a change of trade lines from the Old World to the New.

The rise of massive American cellulose companies investing heavily in British Columbia forest lands and production plants and combined them into large worldwide complexes of industries whose main market is the pulp, lumber and cellulose-hungry industries of the United States accelerated and consolidated the change.

Six days a week, lumberjacks worked from dawn to sunset, lived closely in shanties (or bunkhouses), whose odor — a mix of smoke, perspiration, and drying clothing — was as repulsive as the bedbugs they nourished for the longest time.

Many of the jungle camps, sometimes known as “shanties,” were supervised by tight regulations; many were alcohol-free; and for the longest period of time, talking during meals was outright outlawed.

Usually, the food was excellent, and plenty of it were laid out. Lumberjacks’ ravenous appetites make sense given their daily calorie count of about 7,000. Moreover, considering the weight usually controlling mealtimes, cooks sometimes let loggers eat for only 10 to 15 minutes.

(Photo credit: University of British Columbia Library).

No Comments