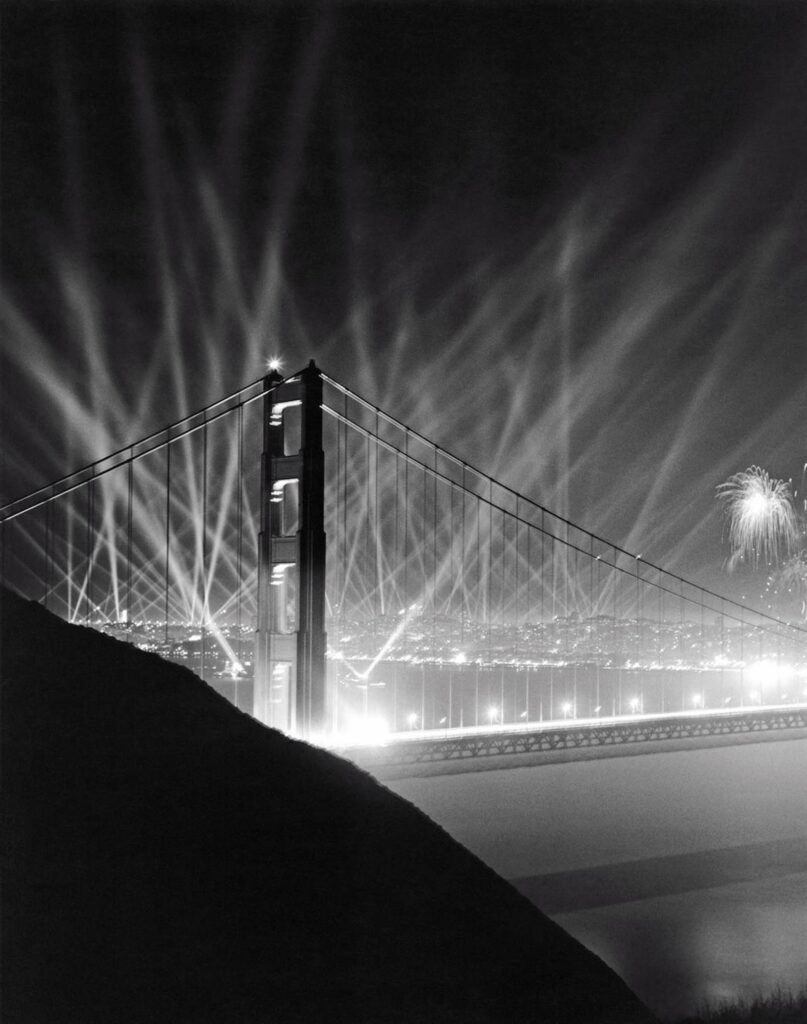

Unquestionably an American landmark, the Golden Gate Bridge’s symbolic impact exceeds that of the Empire State Building and Statue of Liberty in part because of its portrayal of optimism, a very American quality.

Its visual relationship of form and environment, goal and design, does not set limits but rather symbolizes Western prospects and Pacific possibilities.

Here the American ideas of hope, possibility, and success blend with the future—shown by the ocean stretching beyond the bridge itself.

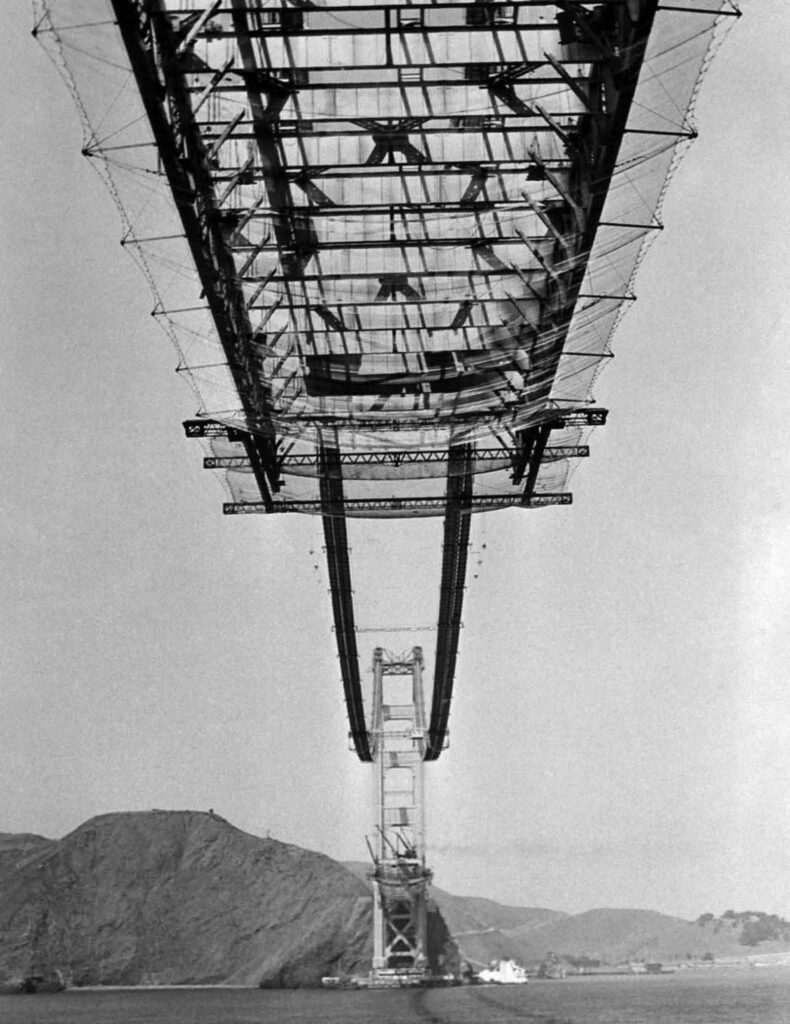

The Pacific Ocean throws powerful gusts, choppy waves, and strong storms into Golden Gate. Besides, the area is an earthquake zone. Scientists had found by the early 1900s that under certain circumstances stiff bridges may break and fall.

A suspension bridge would be the ideal fit for the Golden Gate, Joseph Strauss and his two engineering advisors, Charles Ellis and Leon Moisseiff, concluded.

Suspension bridges were proliferating in the 1930s as work on the Golden Gate Bridge started. Usually, the main supports of early bridge designs were under the road to keep it upright.

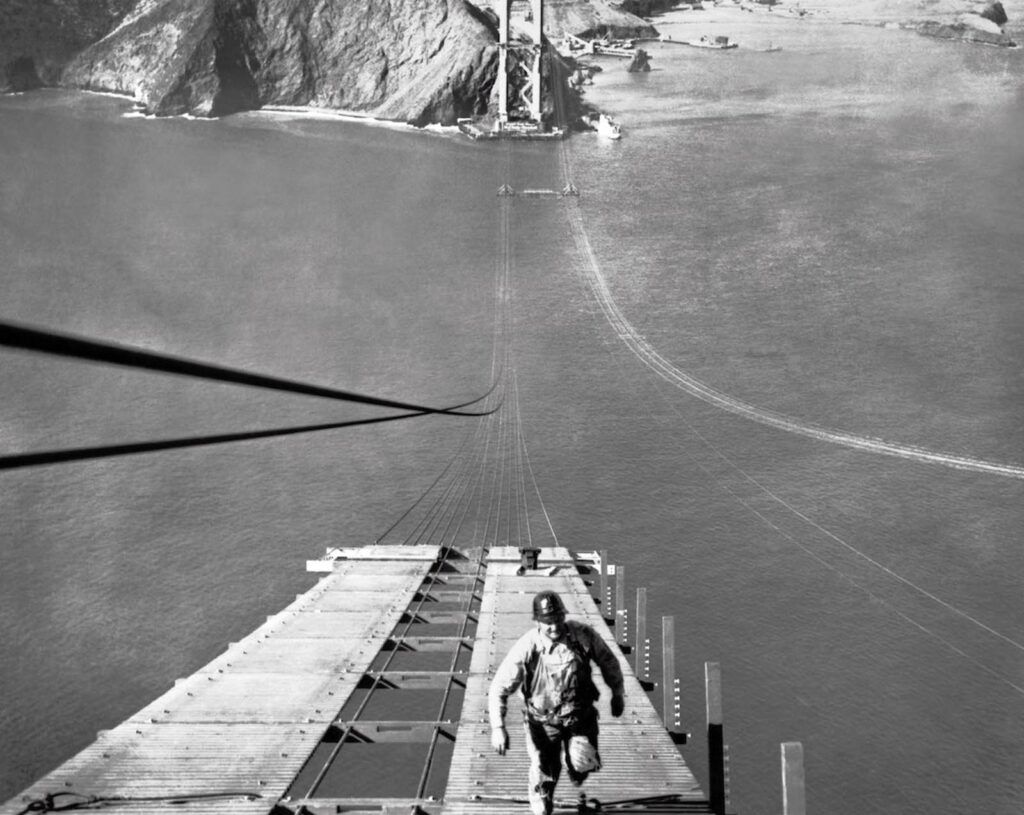

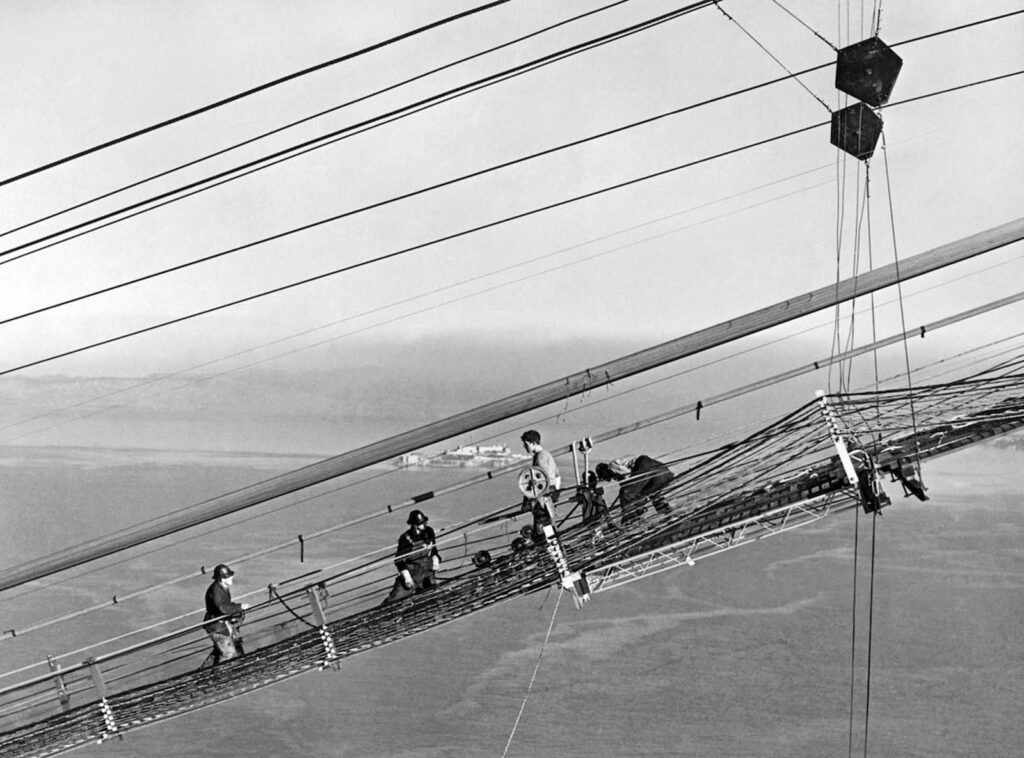

From sturdy wire cables, the road of a suspension bridge is hanged or suspended. Flexible wires let the bridge swing in severe winds without breaking and expand and shrink in hot and cold conditions.

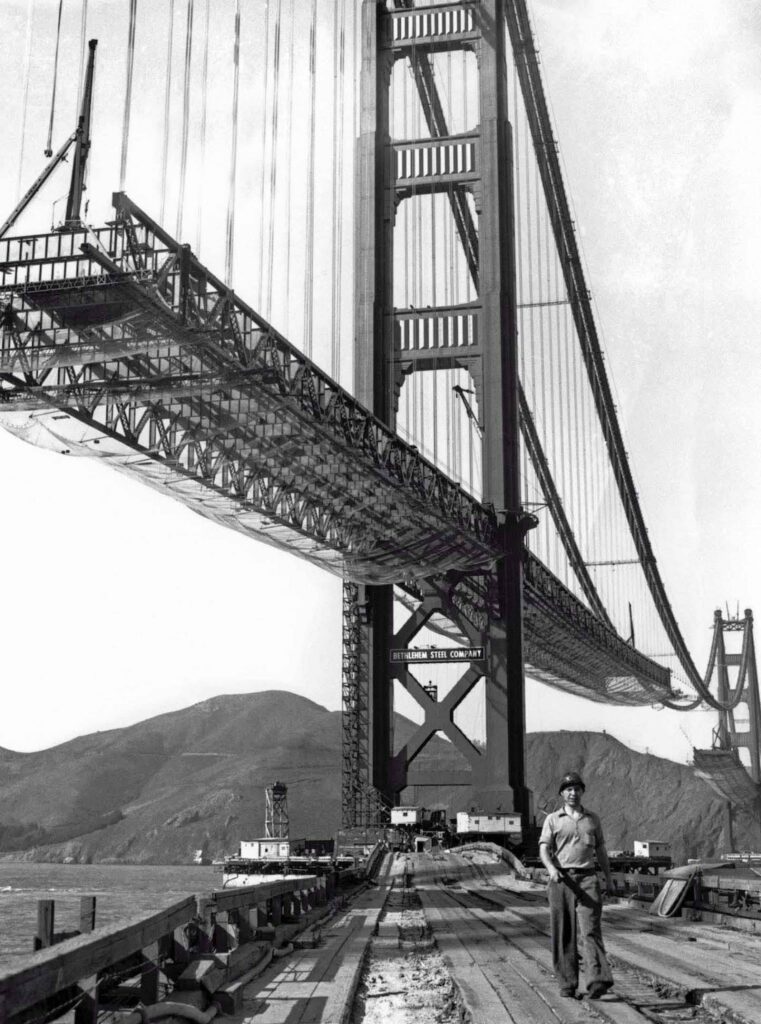

Workers dynamited rocks and excavated pits for the anchorages of the bridge starting the project in January 1933.

Made of thick cement, the anchorages “anchorite” the bridge to the earth by holding the ends of the huge cables at opposing coasts. When I returned a month later, the first chore was really easy in comparison to the enormous distances ahead.

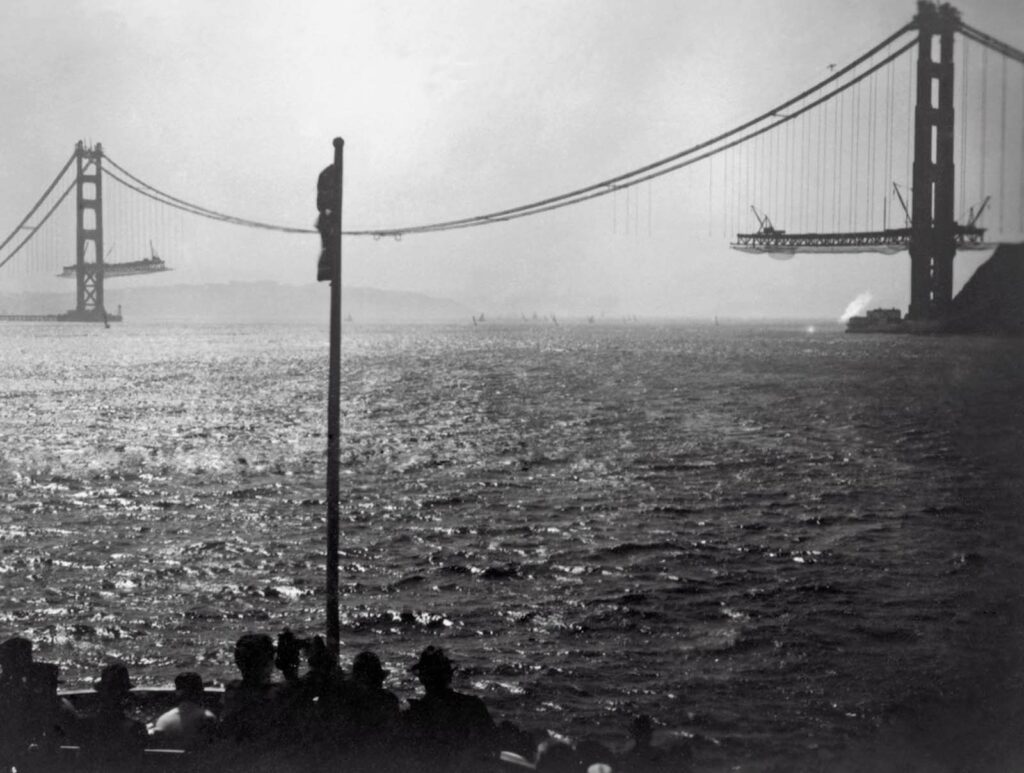

In the annals of bridge construction, the Golden Gate Bridge broke fresh ground. The building endeavor was costly, risky, and time-consuming; never before had a bridge been tried at an ocean entry.

By June 1933, workers had quickly built the concrete north pier, the cement pillar supporting the north tower.

But the south pier was to be constructed 100 feet (30.5 m) below the surface of the harsh Pacific Ocean.

This meant the work of divers and building a massive protective concrete barrier around the pier known as a fender. Completing the south pier needed almost a year and a half.

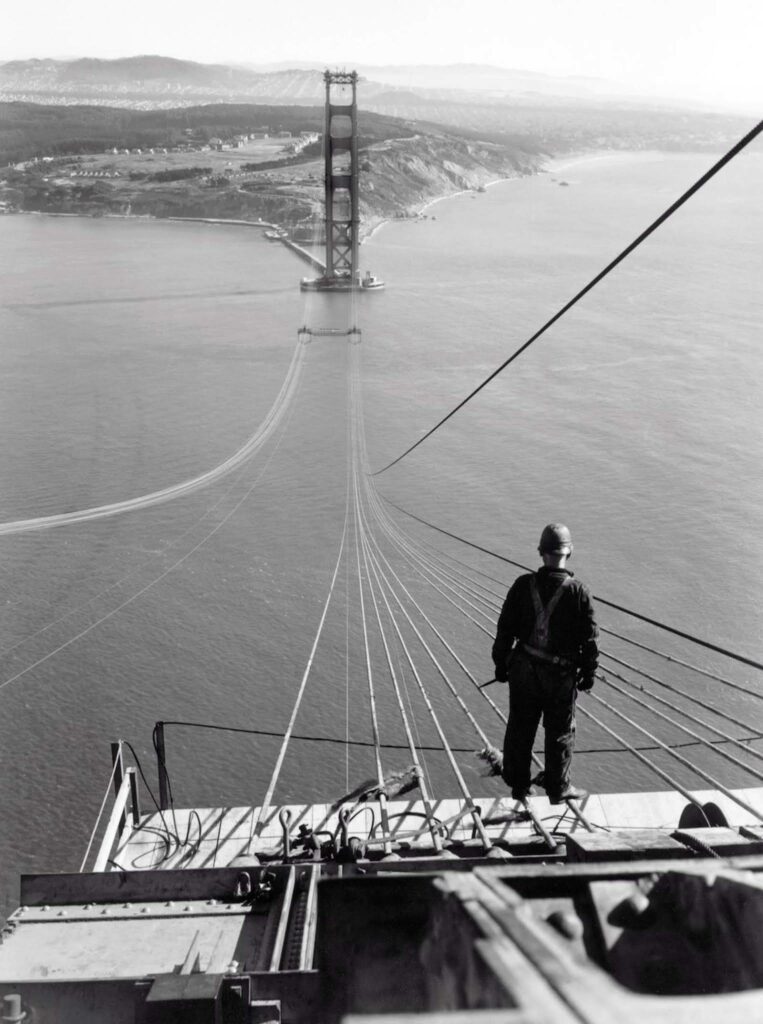

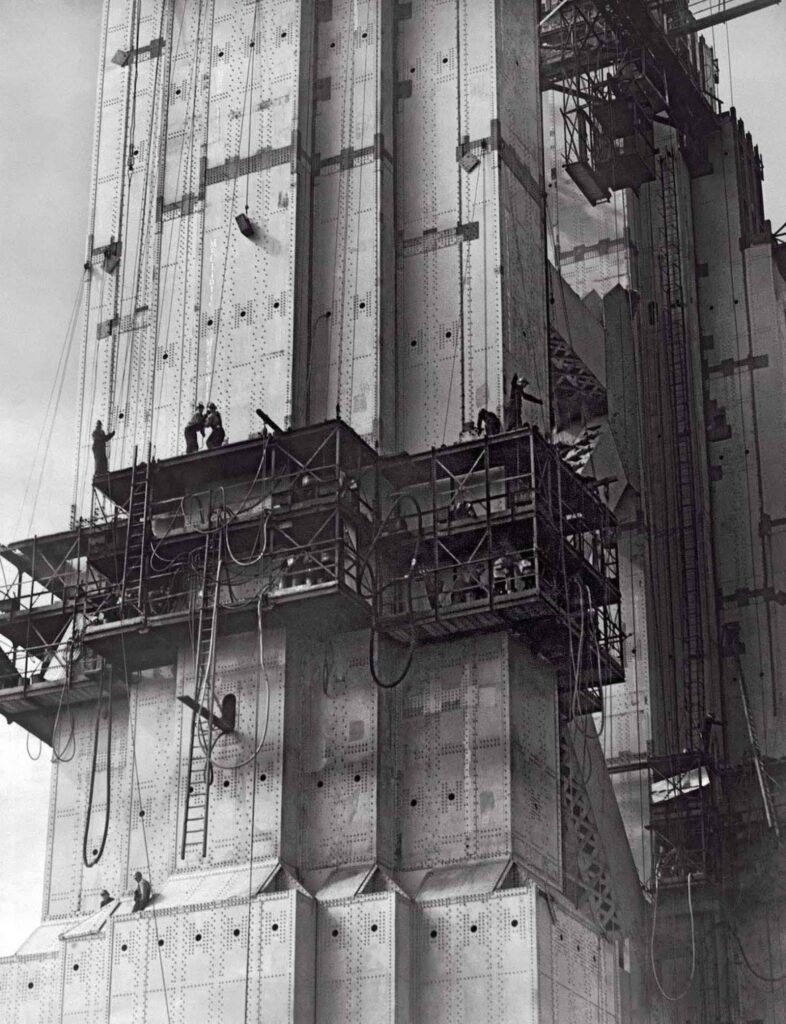

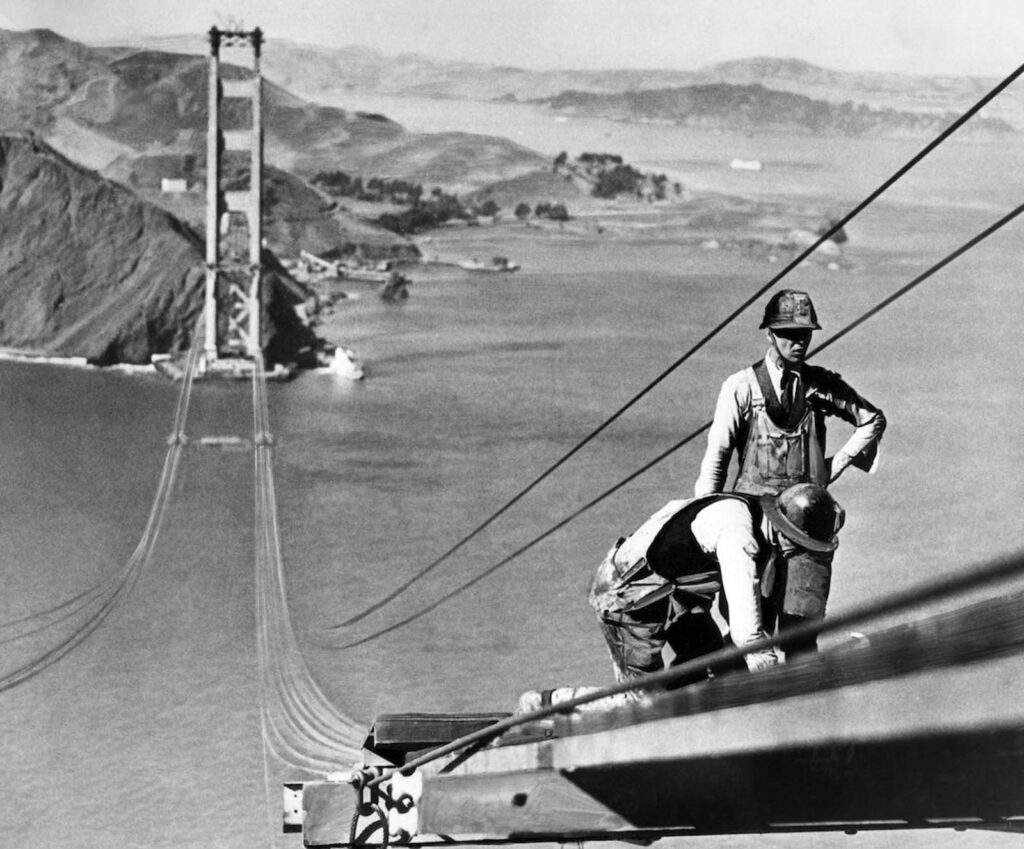

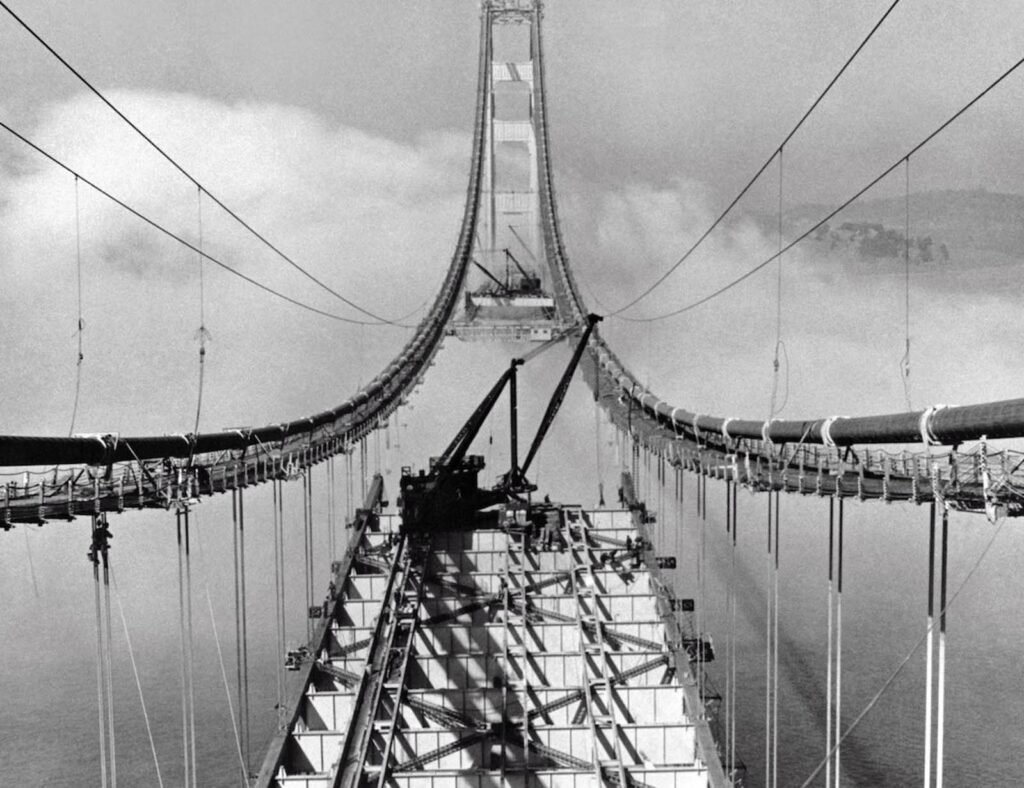

Supported by the piers, the two towers of the bridge were built from prefabricated steel components.

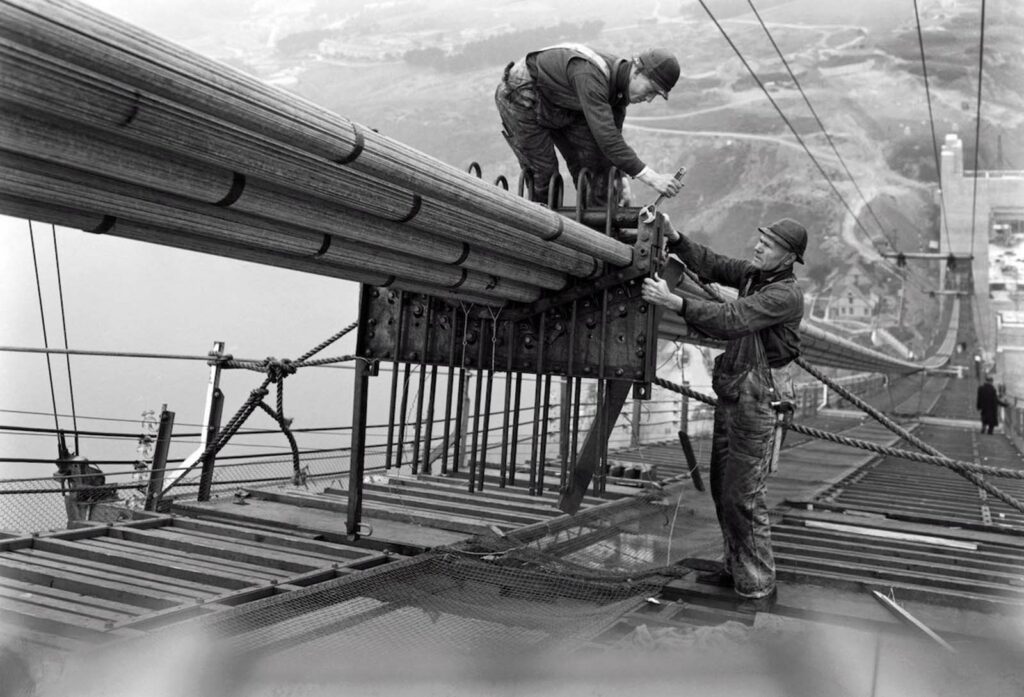

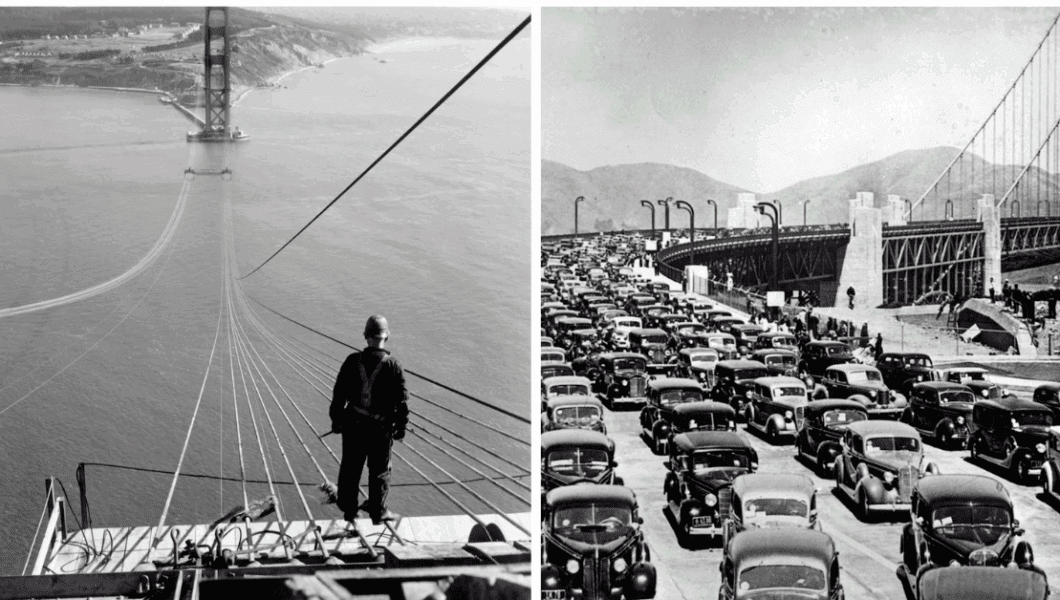

Workers riveted the steel components together from the piers upward for two years until the constructions soared skyward. As they ascended, the laborer’s and their foramen became more careful.

Every job required hard helmets, and a large safety nets hung beneath the bridge. Every $1 million spent at that time in bridge building usually resulted in one death.

The nets rescued nineteen others as ten workmen perished in the plunge from the wet, slick steel of the Golden Gate Bridge.

The bridge has been much used and appreciated from its opening. In the first hour of operation, eighteen hundred autos and 2,500 pedestrians crossed; by midnight of opening day, an estimated 25,000 cars and nineteen thousand pedestrians had paid their toll— fifty cents per car, five cents each foot.

Through its first fiscal year, 3,326,521 automobiles had passed. There were thirty-million annually by the end of 1970.

Given such figures, it is not surprising that by July 1971 the bridge was paid for—the cost was 35 million dollars.

For a bridge built in Chicago, manufactured in Pennsylvania, and transported over the Panama Canal, the American Society of Civil Engineers also named the bridge as one of the seven wonders of the United States in 1994. This is not surprising either.

Constant maintenance balances the popularity and frame of the bridge. The bridge has great need for upgrading and retrofitting since it is roughly 12 miles east of the San Andreas fault and heavy storms are a constant hazard.

Amazingly, the bridge has already survived strong winds, hurricanes, and earthquakes including the terrible Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989.

One secret is the bridge deck’s capacity for vertical or horizontal movement spanning seven feet in either direction.

Another is that the bridge consists of six elements—approaches, piers, towers, highway, centre span, and cables—not one so that each moves separately.

Still, the skillful integration of the bridge with the surroundings keeps its integrity without compromising beauty by integrating all these elements.

(Photo credit: Underwood Archives / Library of Congress / Getty Images / Article based on Golden Gate Bridge by Jennifer Fandel and Golden Gate Bridge: History and Design of an Icon By Donald MacDonald, Ira Nadel).

No Comments