At 3:17 PM, a Facebook post in our local parents’ group called me a poisoner of children.

Not a “concerned librarian” or a “misguided educator.” Not even “someone pushing an agenda.”

A poisoner.

The post had my full name in it. Margaret Miller. But the kids call me Ms. Peggy, mostly because it sounds friendlier, like someone who will help you find the book you’re too embarrassed to ask for.

By 4:00 PM, my email was a sewer. Caps lock. Bible verses. Threats. People promising to “expose” me. People who had never stepped into Jefferson High’s library telling the internet I was hiding filth behind book covers.

By 5:00 PM, someone wrote that they were calling the school board and the local news. A few replies suggested they should “watch my house.”

I stared at my computer screen and felt something in my chest go cold, like my body was trying to protect itself by turning into stone.

The original post came from Karen Fields. She wasn’t an anonymous stranger. She had a face everyone recognized. A mom who volunteered. A mom who led the fundraiser drives. A mom who always seemed to know what people should be afraid of next.

She posted screenshots. Torn little pieces of books like trophy scraps.

One paragraph from a novel about slavery.

A panel from a graphic novel where two boys held hands.

A page from a book about depression, the kind of book that doesn’t wrap pain in pretty paper.

She wrote that our shelves were hiding “graphic filth” and “anti-American propaganda.”

It spread fast in our small Ohio town, faster than weather updates, faster than missing dog posts. I watched the shares climb while the truth stayed locked behind context, unable to keep up.

Screenshots move faster than context. They always will.

I could have shut the library down. I could have drafted a statement. I could have waited for the district’s legal team to tell me what to say.

Instead, I made coffee.

Not the small polite pot I brewed for myself in the mornings, but a full, stubborn pot like we were hosting a wake. Something hot to keep the shaking from showing.

I straightened my cardigan. I smoothed my skirt. I looked at myself in the bathroom mirror and saw how tired I looked, even with my lipstick on.

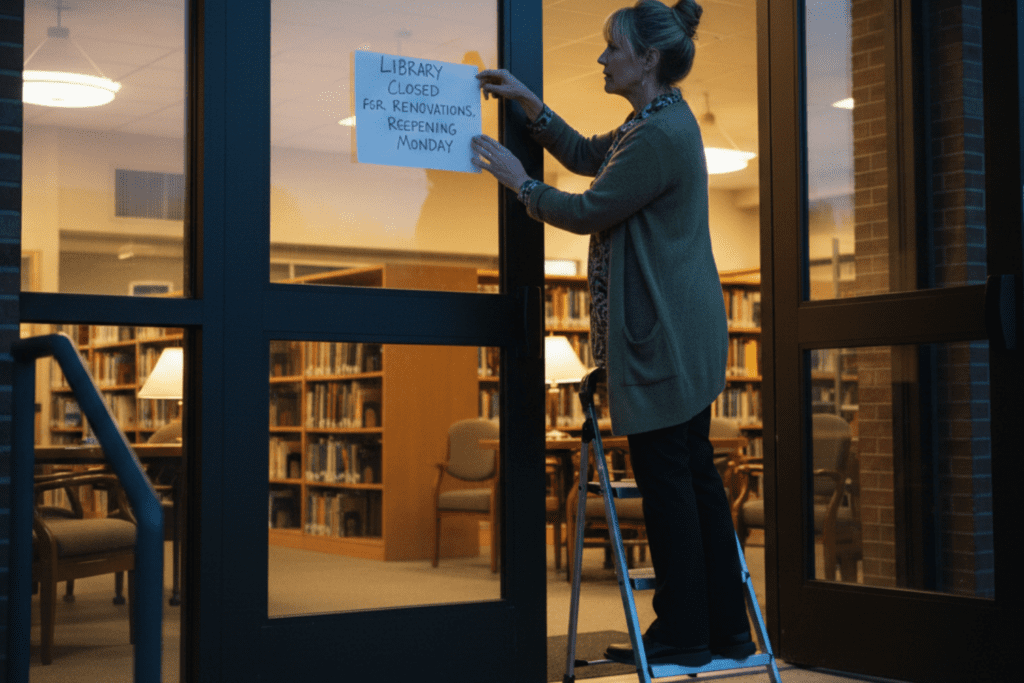

Then I took a marker and a sheet of printer paper and wrote a sign in thick letters, the kind you can’t pretend not to read.

OPEN SHELF NIGHT. 8 PM. ASK ME ANYTHING. ALL BOOKS ON TRIAL.

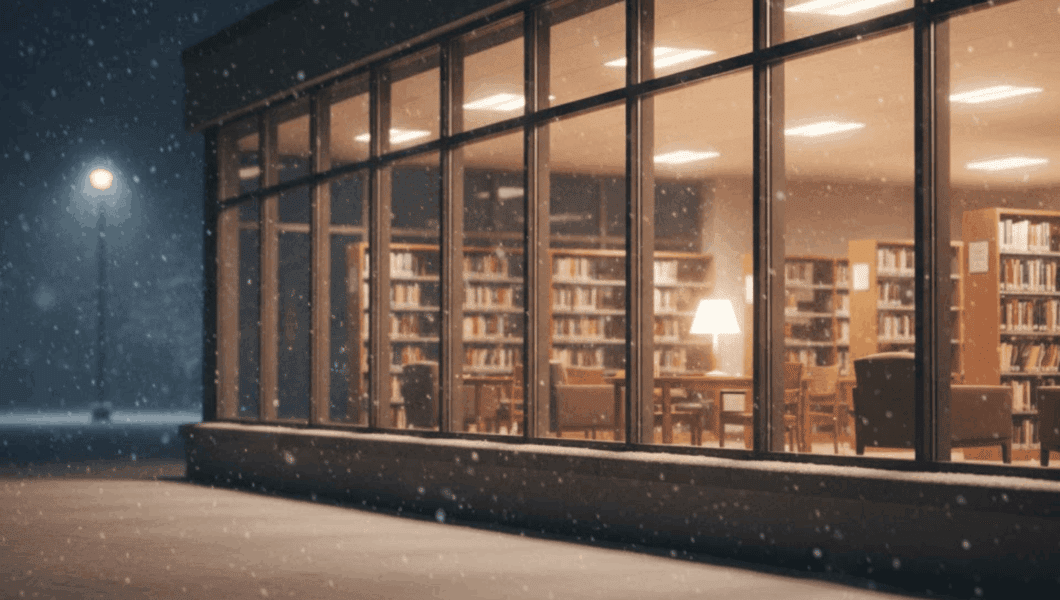

I taped it to the glass door.

For a moment, my hands stayed pressed against the paper like I was trying to hold it there by sheer will.

Then I unlocked the doors and let the building breathe.

The first people who came were the quiet ones.

A few teachers who looked like they hadn’t been truly rested since August. Our local pastor, holding his coat like he wasn’t sure if he should be there. A grandfather who donated the quilt hanging above the reading nook, the one with faded squares and bright stitching that always makes the library feel more like a home than an institution.

They came in like you enter a hospital. Carefully. Respectfully. Like the place might be in pain.

Then the heat arrived.

A man walked in filming on his phone, selfie stick extended like he was broadcasting a hunt. Four parents came in matching “Parents for Principles” t-shirts, their jaws tight, their eyes scanning the shelves like they were searching for contraband.

Behind them came others clutching printed screenshots. Paper copies of outrage, wrinkled at the corners from being gripped too hard.

And then Karen Fields walked in.

Her chin was lifted like she’d already won.

Beside her, half-hidden in the shadow of her confidence, was her son.

Tyler.

He wore a hoodie pulled up despite the heat running. He held a sketchbook against his chest like it was a shield. He didn’t look at anyone. Not even his mother.

My stomach twisted at the sight of him.

Because I recognized the posture.

That’s the posture of a kid trying to disappear while the adults around him turn everything into a war.

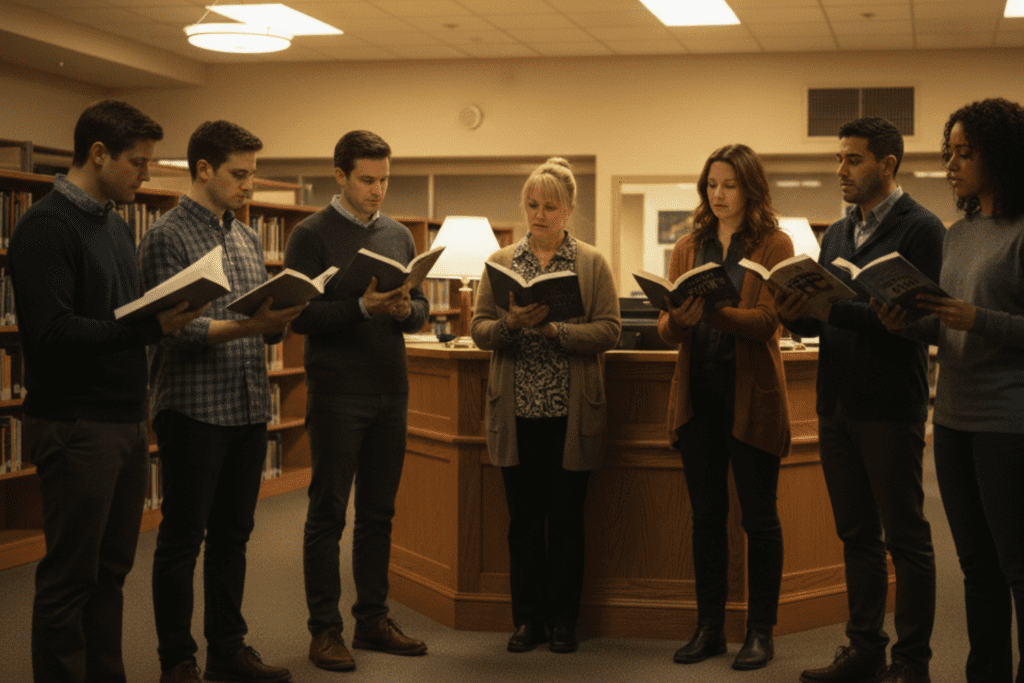

I stood behind the circulation desk. My mouth tasted like coffee and nerves.

“Thank you for coming,” I said, and my voice surprised me by not shaking. “There are no secrets here. Here’s what we’ll do tonight. I’ll explain how we choose books. Then we’ll look at any book, any page you want. I’ll answer every question. If I don’t know the answer, I will say so.”

“Do you have parental controls?” a man called out from the back.

His voice had a tone I’ve learned to recognize. The tone of someone who already decided what kind of person I am.

“We do,” I said. “It’s an opt-out form. You can list specific titles, authors, or entire genres you don’t want your student to check out. We honor it. Period.”

A few people blinked. Some looked briefly disappointed, like they expected a fight.

I clicked to a slide. Our policy. Our process. The review journals we use. School Library Journal. Kirkus. Professional sources, not viral posts. I explained the committee that approves acquisitions: two teachers, a counselor, two parents, a student, and me.

No secret society. Just long meetings and spreadsheets.

Karen raised her phone.

“Let’s see the filth,” she said loudly. “Page ninety.”

It landed like a slap. Someone behind her snorted a laugh.

“Great,” I said. I went to the shelf and retrieved five copies of the novel. “Page ninety is a scene where the main character, a teenage boy, describes his depression. It’s raw.”

They flipped pages like detectives. Eyes narrowed.

I waited.

“Now,” I said quietly, “please read page ninety-two.”

“What’s on ninety-two?” someone asked.

“That’s where he calls a suicide hotline,” I replied. “Page ninety-three is where he tells his mother. We don’t keep this book because we want kids to hurt. We keep it because some of them are already hurting, and they need words for it.”

The library went still in that specific way people get when their anger realizes it might not be righteous.

We moved to the graphic novel next.

“This is the screenshot,” Karen said, as if she’d caught me smuggling.

I set the book open on a table. “It’s two panels,” I said. “Two awkward kids figuring out who they are. There’s no explicit content. No pornography. It’s just… a moment.”

A man muttered something about “values.”

I didn’t argue. I’ve learned arguing isn’t always for truth. Sometimes it’s for performance.

Instead, I picked up the book and read the scene out loud, softly, like it was meant to be heard with care.

A boy saying he doesn’t know why his chest tightens when his friend smiles.

A boy feeling afraid of being found out.

A boy hoping maybe he isn’t broken.

You could feel the room changing. The air losing its sharpness.

Then came the history book labeled “anti-American.”

The screenshot was a paragraph about Japanese-American internment camps.

“This is American history,” I said. “Not a rumor, not propaganda. It happened here. It’s ours.”

Someone said, “Why do kids need to hear this?”

I looked toward the shelves and thought of students who have already heard worse in their own homes. Students who have already lived through hate dressed up as tradition.

“Because the point of education isn’t comfort,” I said. “It’s truth. We can’t be proud of our triumphs if we pretend our failures never existed.”

A teacher near the back exhaled like she’d been holding her breath.

Karen’s expression stayed hard, but less certain now, like the anger had started to wobble under its own weight.

We’d been going nearly an hour when a small voice rose from the back.

Not angry. Not performative. Just real.

“Do you have… anything about feeling stuck?”

Tyler.

He hadn’t moved much all night. But his hoodie was down now, and his face looked pale under the library lights.

He held up his sketchbook a little, like he was asking permission to exist.

“Like,” he said, and his voice broke slightly, “you draw. But it feels like your head is full of static. And you can’t…”

He didn’t finish.

Karen snapped her head toward him. Her hand flew to his arm. “Tyler, not now.”

The whole room saw it. The quick grab. The instinct to silence.

I stepped out from behind the desk.

“Stuck,” I repeated softly, meeting Tyler’s eyes like I was speaking only to him. “I know that feeling.”

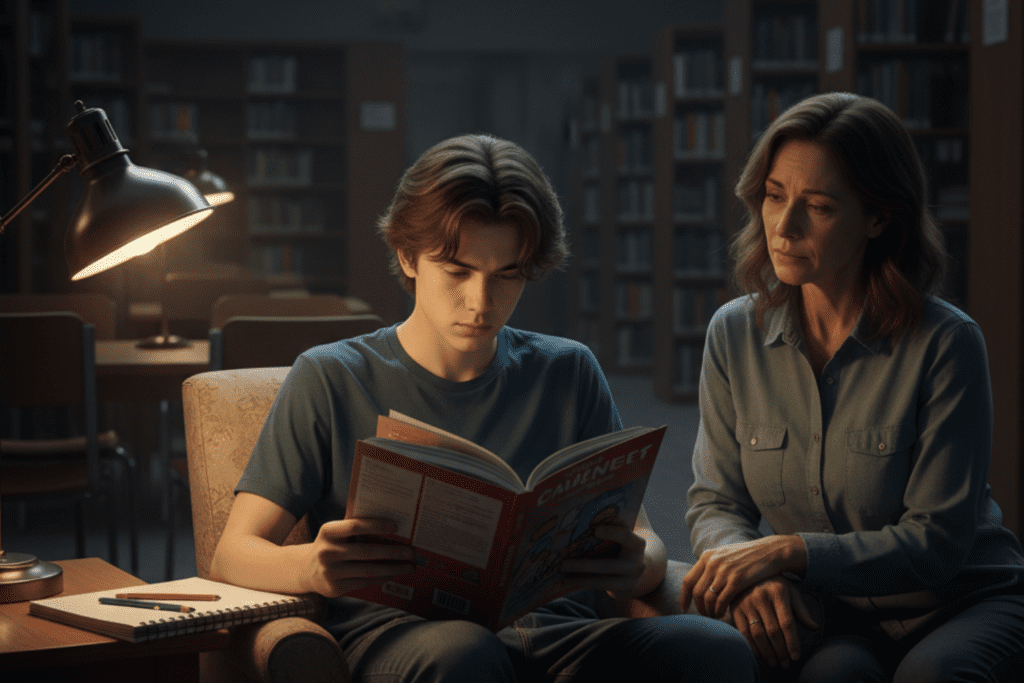

I walked to the YA section and pulled a graphic novel. Not one of the books on trial. Not one of the books that gets dragged through Facebook.

Just a story about a teen who uses art to survive his parents’ divorce. A teen who doesn’t have the right words, only lines on paper.

I handed it to him.

“This one has helped some of our art kids,” I said. “You can read the first chapters here. Your mom can sit with you. If she hates a page, you can skip it.”

Tyler looked down at the cover like it was a door he didn’t know he was allowed to open.

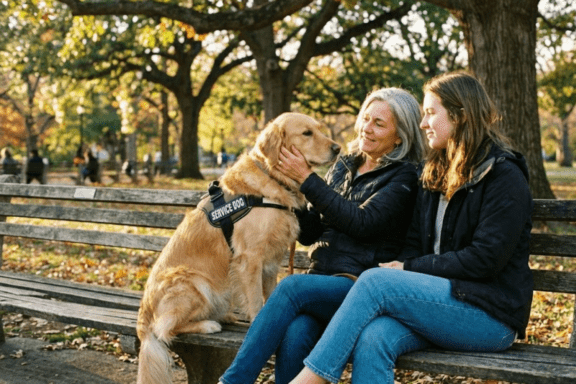

Then he sat down under the reading lamp and started reading.

On page two, his shoulders dropped.

Karen stared at the book in her son’s hands as if it had turned into something else entirely.

The anger on her face cracked. The certainty collapsed into something older and more human.

Fear.

The kind you can’t pretend is moral.

“I’m just trying to protect him,” she whispered, like the room had shrunk into a confession booth.

“I know,” I said. “But you can’t protect him from his own feelings. You can only sit with him while he has them.”

And Karen did something that felt impossible ten minutes earlier.

She pulled up a chair.

She sat down beside him.

After that, the room lost its appetite for war.

The man with the camera stopped filming. The parents in matching shirts stopped whispering to each other. A pastor came up and asked quietly if we had C.S. Lewis.

We did.

A veteran asked for books on the 101st Airborne. I handed him three titles and watched him smile like the library still mattered.

People wandered the shelves and asked normal questions again. Questions that weren’t traps.

One teacher sat in the corner and cried without making noise.

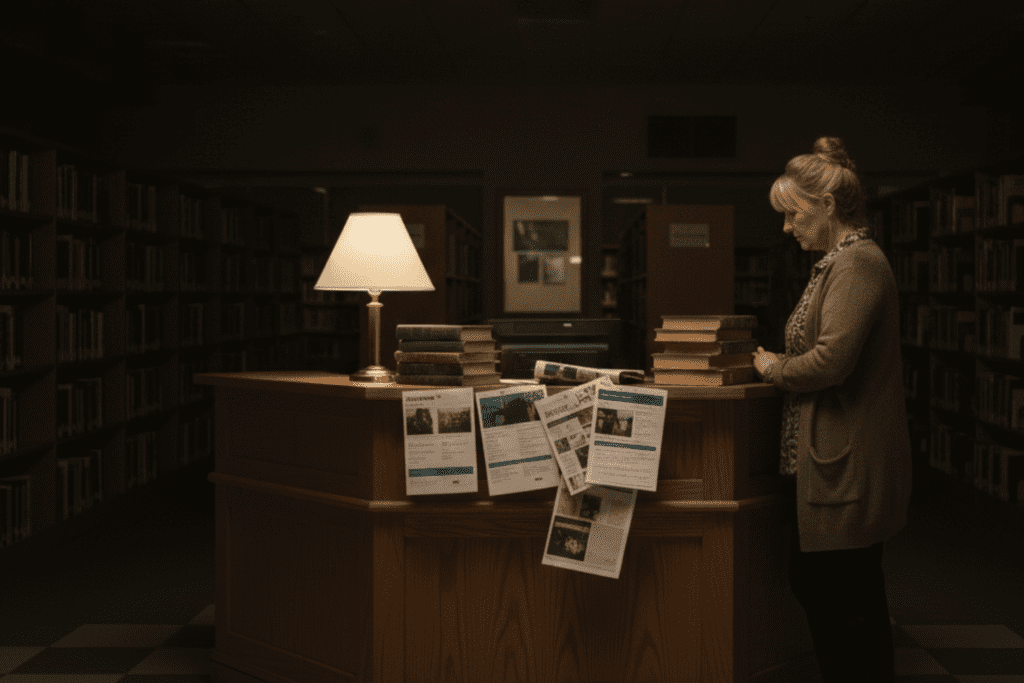

By 10 PM, the room was almost empty.

Only Karen and Tyler remained, still under the lamp. Tyler turning pages like he was drinking water for the first time in a long time. Karen looking at him like she’d forgotten what he looked like when he wasn’t performing for her expectations.

I didn’t interrupt.

I wiped down tables quietly, collecting the abandoned printouts of screenshots left behind like shed skin.

When Karen finally stood, she didn’t look at me right away.

She touched her son’s shoulder. He closed the book carefully, like it was something alive.

At the circulation desk, she hesitated.

“I didn’t…” she began.

I didn’t let her force it into an apology she wasn’t ready for.

“It’s a scary world,” I said. “You love him. That’s not a crime.”

Karen swallowed. Her eyes were red.

“Can he check it out?” she asked.

Tyler’s head snapped up, surprised.

“Yes,” I said, smiling gently. “He can.”

When they left, the library felt different. Like it had been washed out by truth.

I turned off the lights one by one, listening to the building settle back into itself.

At my desk, I saw my hands trembling slightly.

Not from fear anymore.

From the strange softness of seeing a room full of angry adults stop long enough to notice a child.

They say books are dangerous.

They’re wrong.

Ignorance is dangerous. Fear is dangerous. Certainty is the most dangerous of all.

A book is just paper and ink. It is a bridge, not a bomb. It isn’t afraid of questions. It opens its pages and waits.

The only stories that demand silence are the ones afraid of the light.

And I learned something last night, standing under fluorescent lights with a microphone I never wanted.

Sometimes the loudest thing you can do in a small town is leave the shelves open.

I went home after midnight. I left the building behind, but I didn’t leave the feeling.

In my kitchen, I made tea and sat at the table the way you do when you don’t want to wake anyone but you also don’t want to be alone with the noise in your head.

My phone buzzed again.

A message request.

From Karen Fields.

It was short.

It said: Thank you for not humiliating us.

I stared at it for a long time, then set the phone face down on the table.

My hands were still shaking.

Because what no one tells you, when you choose a job like mine, is that the work is not just organizing books.

The work is standing still while people throw their fear at you.

The work is keeping the door open anyway.

In bed, I couldn’t sleep. I kept seeing Tyler’s face when he realized he was allowed to ask for help without being punished for it.

Outside, the streetlight lit the snow on the sidewalk. A hard pale glow. Quiet. Steady.

I thought about the word poisoner.

How easily people can assign it.

How they never consider the opposite question.

What if the library isn’t poisoning kids?

What if it’s the antidote?

No Comments