An iron lung, also known as a negative pressure ventilator, is a medical device that helps a person breathe when they can’t control their muscles or when breathing is too hard for them.

It lowers the pressure surrounding the thorax, which makes the rib cage bigger and pulls air into the lungs.

Polio causes the body to lose control of its muscles, especially the diaphragm. This gadget controls the pressure by artificially raising and lowering it so that breathing is feasible. The diaphragm uses pressure to control the intake of oxygen by expanding and decreasing the pressure in the lungs, which lets air flow in.

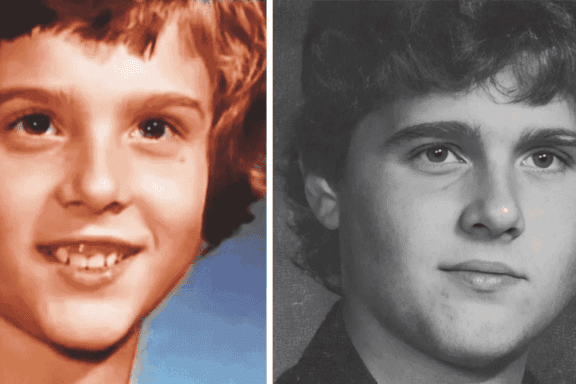

Paulo Henrique Machado, a Brazilian man who has been in the hospital for 45 years because he got polio as a child:

During his early years, he had to live in what was dubbed a “torpedo,” which was basically an iron lung that surrounded his body. He had to make his own “universe” inside the jail of the hospital.

His first memories are of “exploring” the hallways of each ward in his wheelchair and going into the rooms of other kids. His only toy was his imagination.

But Paulo and Eliana (his hospital buddy) watched all of their pals die, one by one, even though they only lived for ten years on average.

Doctors never figured out why Paulo and Eliana lived longer than the others, but they say that the awful event has brought them closer together.

“It was hard,” Machado says. “Every loss was like a dismemberment, you know, like mutilation.” There are only two of us left now: Eliana and me. Paulo and Eliana are at a significant risk of becoming sick, therefore they don’t leave the hospital very often.

Mary Virginia’s story is another one of surviving the iron lung:

Mary Virginia came from a wealthy household and was born in 1930. She had a good childhood until the summer of 1937. Mary Virginia had a great time in the neighbourhood pool.

She felt a little fuzzy right before bed the next day. Her mum put her hand on her forehead. The girl had a slight temperature, so her mum phoned the doctor.

Mary Virginia couldn’t move her legs or arms after a few hours. She was in a hospital in an iron lung two days later.

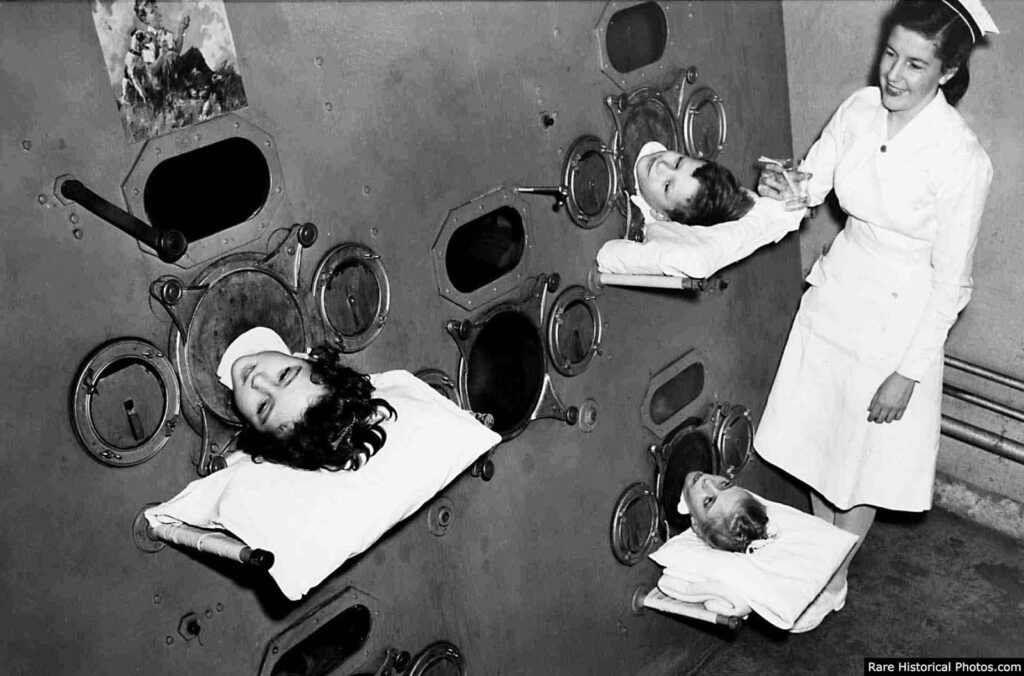

She informed her granddaughter that she used to share an iron lung with four other kids at a time, which she named a “Emerson.”

There were a lot of kids in the hospital who had polio. There was a lot of turnover. In six months, she and just two other people from the first group she saw were still there.

In the communal iron lung, turnover was high for a sad reason: kids perished. Mary Virginia stopped counting her lost friends when she got to 24 since she didn’t know how to count higher than that.

Since then, she didn’t like the number 24 since it reminded her of the kids she witnessed die. Mary Virginia lived in the iron lung for three to four years.

To keep her muscles from getting weak, the nurses would move her arms and legs about. Her parents came to see her a lot while she was in the hospital, but because they were rich, the cost and length of the train ride meant they couldn’t come as often as they would have liked.

Mary Virginia’s mum always felt bad about that. Even so, they saw Mary Virginia more often than most parents saw their kids.

Heather, Mary Virginia’s granddaughter, remembers her grandmother telling her that her mother sent “knitted hats and little things for the kids.” “And books, books were very important.”

How the patients would use the bathroom?

The front of the iron lung, where the patient’s head comes out, is attached to the “tin can.” The buckles can be undone and the “tin can” can be dragged out, exposing the patient’s body on the bed.

A nurse lifts him up and slides a bedpan under him. The iron lung is then closed so that it may breathe again. To get rid of the pan, the process is done again.

About Polio

Polio is a virus that can cause paralysis and even death. It is almost gone in the developed world. Polio is a very contagious disease that affects the nervous system and can cause paralysis, incapacity, and even death.

The symptoms, which include pain and weakness, exhaustion, and muscle loss, might show up anywhere from 15 to 50 years after the disease first appeared.

The invention of the iron lung, a contraption that surrounds the body and fills the lungs with air by making the chest lift, was one of the biggest steps forward.

Before it was invented, a lot of kids with polio died. Polio is no longer an issue in the United States, but it is still a problem in Nigeria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

In the early 1900s, polio was one of the most feared diseases in developed countries. It paralysed hundreds of thousands of children every year.

Polio is a very contagious disease that assaults the nerve system and can cause paralysis, incapacity, and even death. The symptoms—pain and weakness, tiredness, and muscle loss—can happen anywhere from 15 to 50 years after the disease first appeared.

More than 21,000 Americans had a paralysing type of polio in 1952, and 3,000 of them died from it. Once someone got sick, the only thing they could do was wait and take care of the symptoms.

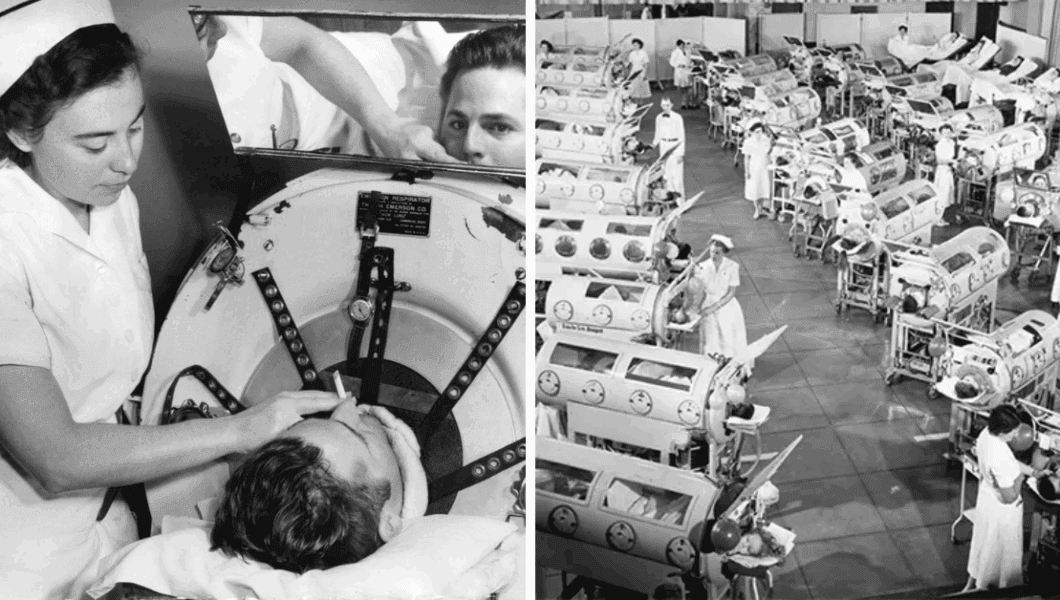

The iron lung, or tank respirator, is the instrument most closely linked to polio. Before it was made, a lot of kids with polio died.

Doctors who treated persons in the early, acute stage of polio found that many of them couldn’t breathe because the virus paralysed muscular regions in their chests.

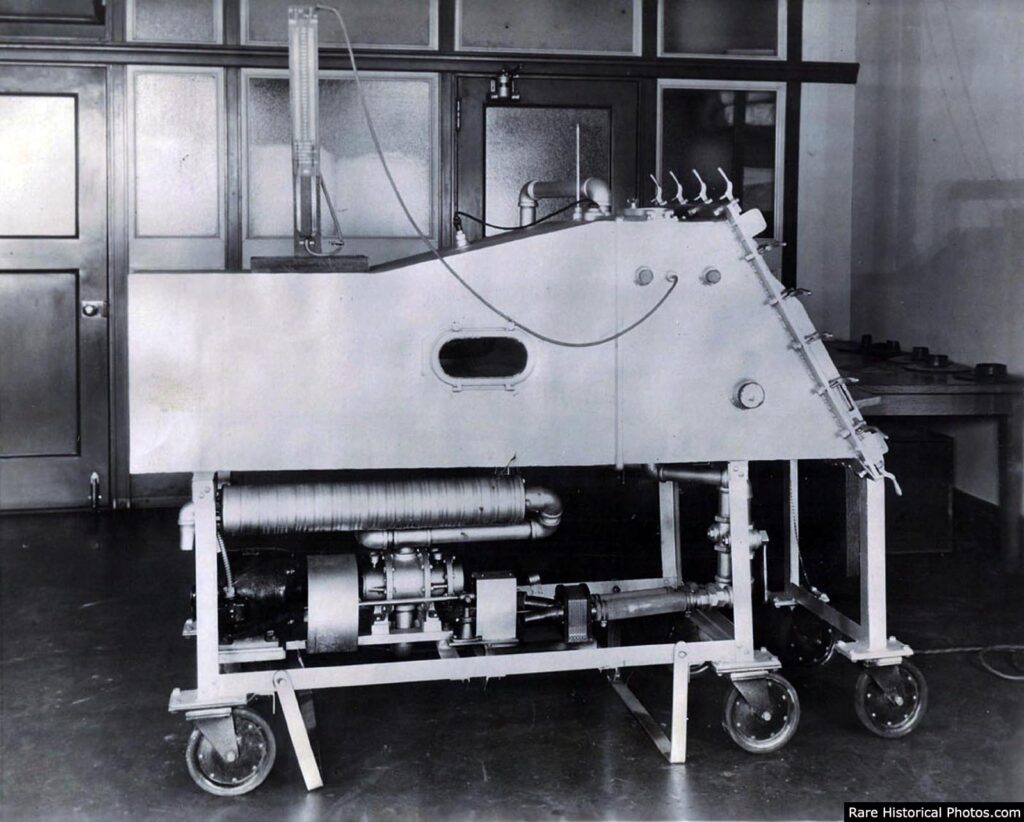

Philip Drinker, Louis Agassiz Shaw, and James Wilson of Harvard came up with the first iron lung to treat polio victims. It was tested on October 12, 1928, at Children’s Hospital in Boston.

The first Drinker iron lung included an electric motor that was connected to two vacuum cleaners. It worked by adjusting the pressure inside the machine.

The chest cavity expands when the pressure drops, striving to fill this space that is only partially empty. The chest cavity gets smaller when the pressure goes up.

This expansion and contraction are like how natural breathing works. The patient could breathe in the machine, but he couldn’t do much else. He could only glance up at a mirror that showed the room behind him.

After that, the iron lung’s design was enhanced by adding a bellows directly to the machine. John Haven Emerson also changed the design to make it cheaper to build.

They made the Emerson Iron Lung until 1970. People with less serious breathing problems employed other breathing devices, like the “rocking bed.”

The iron lung saved the lives of many thousands of people during the polio outbreaks, but it was big, heavy, and incredibly expensive. In the 1930s, an iron lung cost around $1,500, which is about the same as the average home.

It was also too expensive to run the machine because patients were stuck in metal chambers for months, years, or even their whole lives. Even with an iron lung, more than 90% of people with bulbar polio died.

These problems led to the creation of newer positive-pressure ventilators and the use of positive-pressure ventilation through tracheostomy. Positive pressure ventilators cut the death rate of bulbar patients from 90% to 20%.

There are two vaccines that are used all around the world to fight polio. Jonas Salk made the first one, tested it in 1952, and told the world about it on April 12, 1955.

The Salk vaccination, sometimes called the inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), is made up of a shot of dead poliovirus.

In 1954, the vaccine was tested to see if it could stop polio. The field trials with the Salk vaccination would become the biggest medical experiment ever.

as getting their licences, vaccination campaigns began. By 1957, as the March of Dimes encouraged mass immunisations, the number of polio cases in the United States dropped dramatically, from a peak of roughly 58,000 cases to barely 5,600 cases.

Eight years after Salk’s triumph, Albert Sabin made an oral polio vaccine (OPV) using a live but weakened (attenuated) virus. In 1957, Sabin’s vaccine was tested on people, and it was approved in 1962.

After the oral polio vaccine was made, the second wave of mass immunisations would cause the number of cases to drop even more. By 1961, there were only 161 cases in the United States.

The final occurrences of paralytic poliomyelitis in the United States were in 1979, when an outbreak happened among the Amish in a few Midwestern states. This was because poliovirus was spreading naturally in the country.

(Photo credit: AP / Steve & Mary DeGenaro / Boston Children’s Hospital Archive / AARC’s Virtual Museum).

No Comments