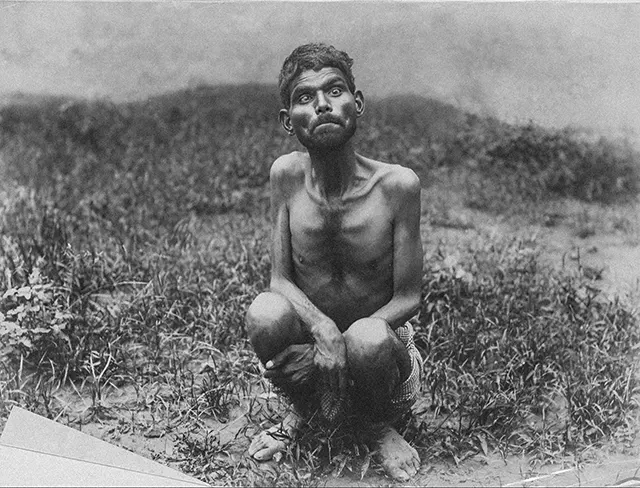

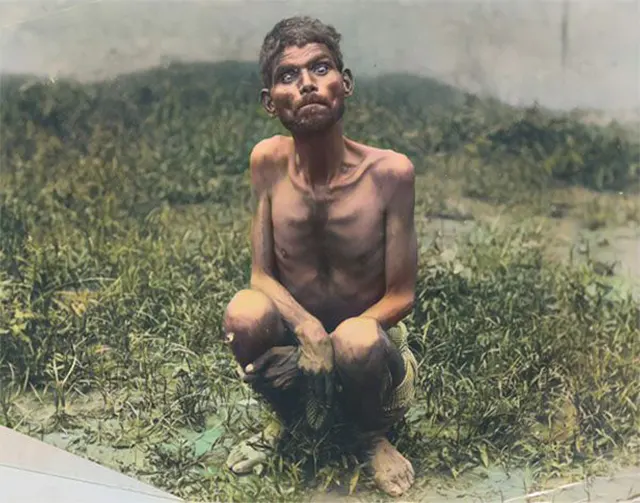

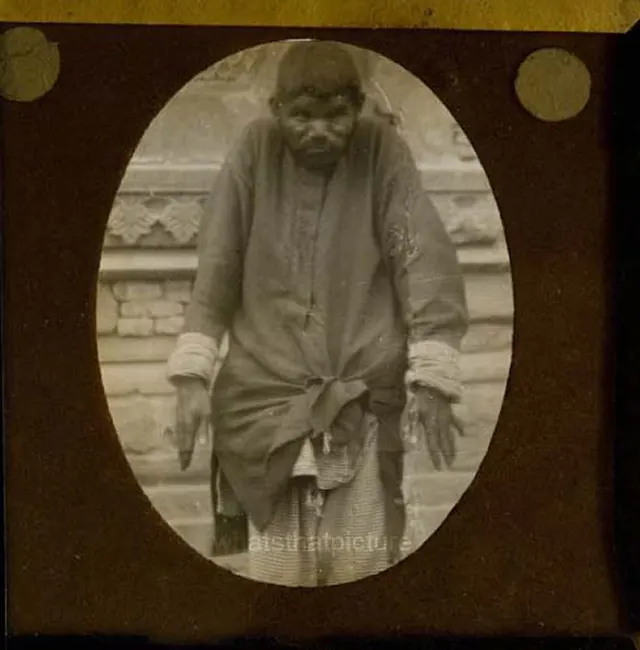

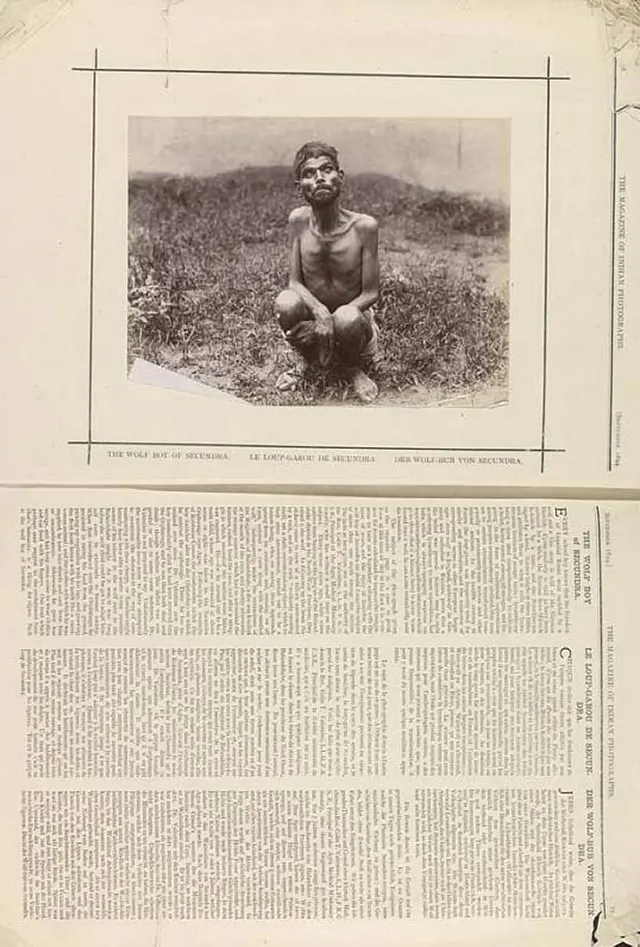

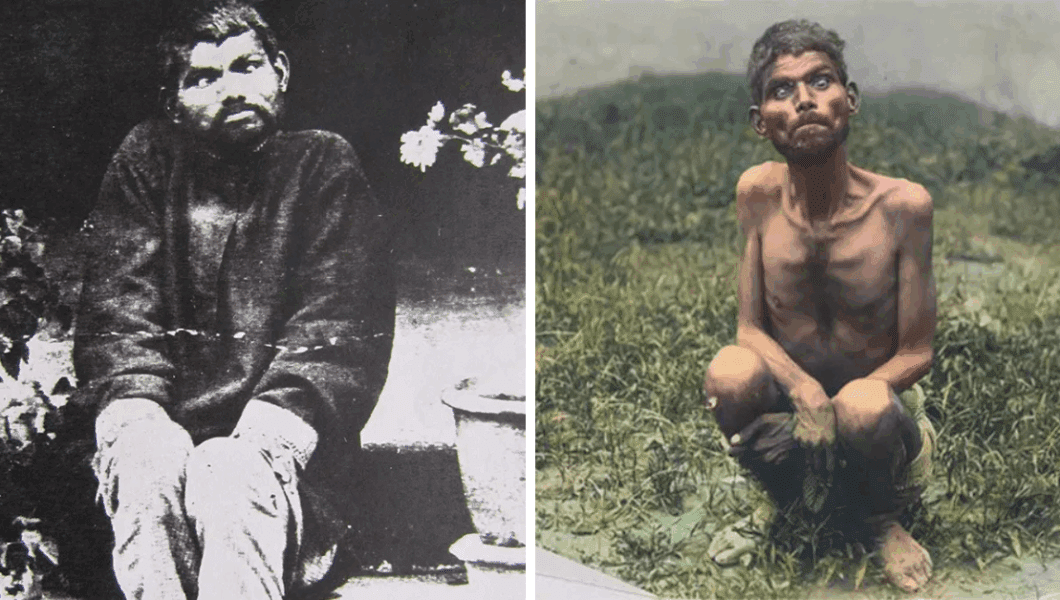

Dina Sanichar’s life was full with sadness and loneliness. He was found as a small boy in the Indian jungle and reared by wolves. He had a hard time adjusting to life with people.

He never learned to speak or connect with other people in a meaningful way, even though people tried to teach him how to do so.

He died in 1895 when he was about 35 years old, leaving behind a story that still haunts everyone who hear it.

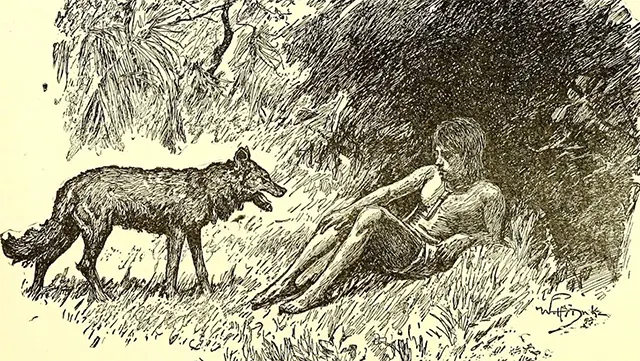

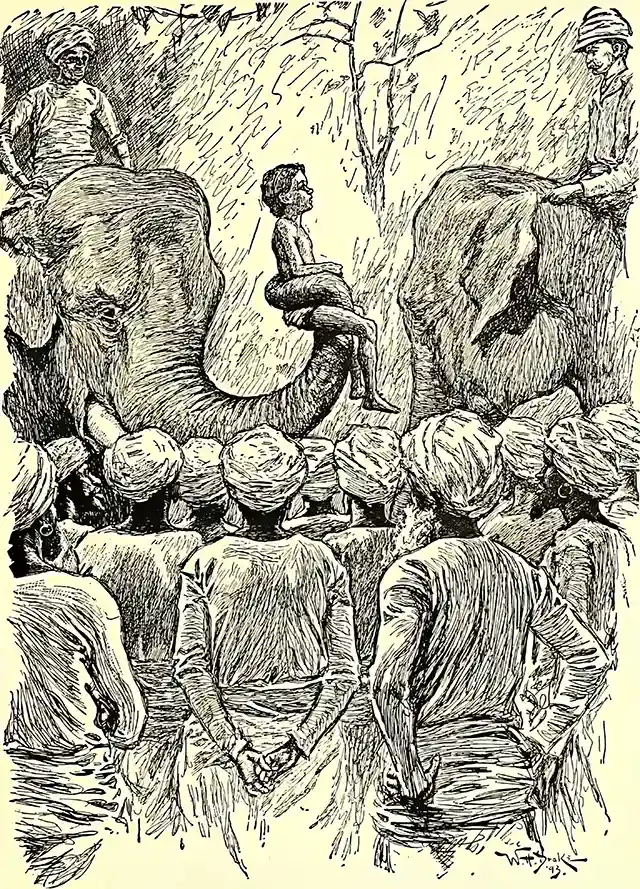

There are some interesting similarities between Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book and Sanichar’s life. The book is about Mowgli, a boy whose parents left him and who was raised by wolves. Mowgli does well in the animal world, but his interactions with people show how complicated his two identities are.

Kipling’s story, on the other hand, has a hopeful message about achieving peace between nature and human civilization and learning more about yourself.

But not many people know that it may have been based on historical events, such the story of Dina Sanichar, who was called the “real-life Mowgli” who thought he was one of the wolves that raised him when he was a child.

The Discovery of Dina Sanichar: Raised by Wolves

In 1867, a group of hunters going through the forests of Bulandshahr, in northern India, saw something strange and scary.

A pack of wolves was closely following a human toddler who was crawling through the thick bush. The group quickly went back into a cave, leaving the hunters startled and scared by what they had just seen.

The hunters were determined to find out what was going on, so they lit fire at the mouth of the cave to get the wolves to come out. The hunters slaughtered the beasts as they came out and saved the youngster.

The youngster, who seemed like he was just six, didn’t seem to know who the hunters were or respond to them. He stayed away from them completely, acting and moving more like the wolves that had nurtured him.

The hunters were worried about his safety in the hard wilderness, so they took him to the Sikandra Mission Orphanage in Agra.

The missionaries gave the boy a name at the orphanage because he didn’t have one. They named him Dina Sanichar after the Hindi word for Saturday, the day he got to the mission.

Dina Sanichar Back Into The Civilized World

People at the Sikandra Mission Orphanage often called Dina Sanichar the “Wolf Boy.” People thought he had been raised by wild animals and had never met a person before.

His actions simply made this idea stronger because it was really animal-like. Sanichar crawled on all fours and had trouble walking straight. He liked to eat raw flesh and often chewed on bones, as if he were honing his teeth.

Erhardt Lewis, the head of the orphanage, wrote to a coworker, “It’s amazing how well they get along on four feet (hands and feet).” “Before they eat or taste anything, they smell it. If they don’t like the smell, they throw it away.”

Talking to Sanichar was quite hard. He didn’t speak any language; instead, he growled and howled like a wolf. Gestures and pointing didn’t work either.

The missionaries tried to help him fit in with people, but Sanichar never learned to speak. The sounds of human language may have been too strange for him to copy, making it almost impossible for him to do so.

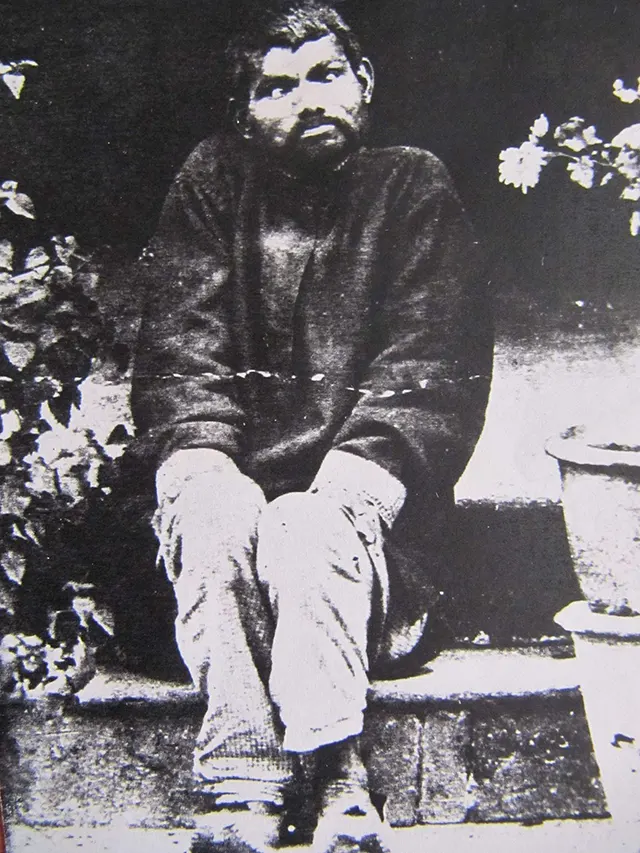

But over time, he started to act like a person. He finally learned to walk upright, clothe himself, and even accomplished what some people might call the strangest thing people do: smoking cigarettes.

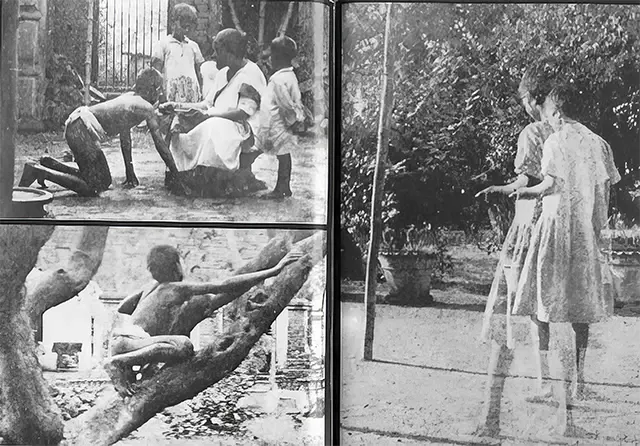

During his time at the orphanage, Dina Sanichar did make a connection with one other person: another wild child found in the Manipuri region of Uttar Pradesh who had also been transferred to Sikandra.

Father Erhardt saw this peculiar interaction and said, “These two boys had a strange bond of sympathy that brought them together. The older boy taught the younger boy how to drink from a cup.”

The orphanage took care of Sanichar throughout the remainder of his life, but even after living among people for more than 20 years, he never entirely got used to their ways.

It appeared like he couldn’t understand social standards or how people usually act, as if the imprint of his early years in the wild was too strong to change. Sanichar died of TB in 1895 when he was 34 years old.

There Were Other Feral Children Living at the Same Orphanage

There were other kids at the Sikandra Mission Orphanage who had colorful pasts besides Dina Sanichar. Erhardt Lewis, the administrator, said that there were two additional boys and a girl at the orphanage who were similarly thought to have been reared by wolves.

Their presence shows that cases like Sanichar’s, while rare, were not completely unusual at that time.

One geographer even said that the orphanage had taken in so many “wolf children” over the years that it became nearly normal.

British general Sir William Henry Sleeman wrote down at least five such stories of kids who had lived in the wilds of India.

In “A Journey through the Kingdom of Oude,” Sleeman recounts one story as follows:

In Sultanpoor, there is presently a youngster who was found alive in a wolf’s lair near Chandour, which is about ten kilometers from Sultanpoor, around two and a half years ago.

A soldier from the native governor of the district was on his way to Chandour to collect some taxes when he witnessed a big female wolf exit her burrow with three pups and a tiny guy about noon.

The child got down on all fours, and it looked like he was getting along well with the old dam and the three whelps. The mother seemed to be watching all four of them with the same attention.

They all went to the river and drank without noticing the trooper, who was sitting on his horse and watching them. The warrior pressed on to cut off and catch the youngster as soon as they were going to turn back. But he ran as quickly as the whelps could and caught up with the elder one.

The ground was bumpy, so the trooper’s horse couldn’t catch up to them. Everyone went into the den, and the trooper got several people from Chandour with pickaxes and dug into the den. The old wolf ran away with her three cubs and the boy after they had dug around six or eight feet.

The soldier got on his horse and chased after them, followed by the fastest young men in the group. The land they had to fly over was more level, so he led them and turned the whelps and kid back toward the men on foot, who caught the child and let the old dam and her three cubs go on their way.

The boy in Sir William Henry Sleeman’s story, like the child who was driven out of the wolf’s den, only lived for a few months after being brought into human society.

Dina Sanichar was not the only “wolf child” found at this time, but his story is different from the others. Sanichar was one of the few who made it to maturity, unlike most others who couldn’t handle the difficulties of adjusting to a new place.

Did Dina Sanichar Really Serve as Kipling’s Inspiration?

It is likely that Rudyard Kipling was inspired by stories of wild children when he wrote The Jungle Book. However, it is still not clear if he knew about Dina Sanichar’s account.

In 1894, Kipling wrote The Jungle Book. This was when stories of “wolf children” from India were getting a lot of attention.

John Lockwood Kipling, Kipling’s father and the illustrator of the first edition of The Jungle Book, also wrote about similar incidents in his 1891 book Beast and Man in India.

In his autobiography, Something of Myself, Kipling wrote that he got ideas from many places, such as the “Masonic Lions of my childhood’s magazine” and H. Rider Haggard’s book Nada the Lily, which is about a man and a wolf who are friends.

In a letter from 1895, Kipling said, “I have stolen from so many stories that it is impossible to remember from whose stories I have stolen.” This is more proof of his creative process.

(Photo credit: Google Books / Wikimedia Commons / Upscaled and enhanced by RHP).

No Comments