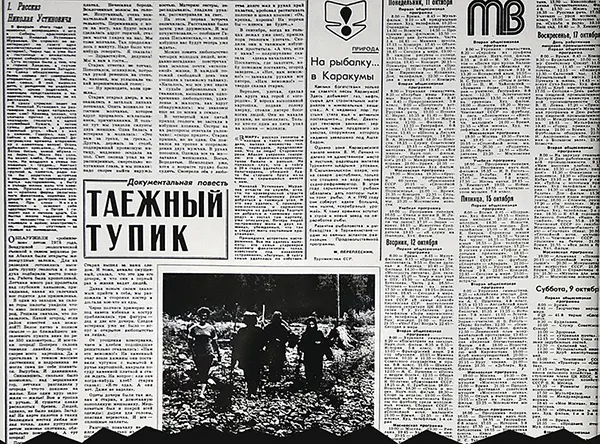

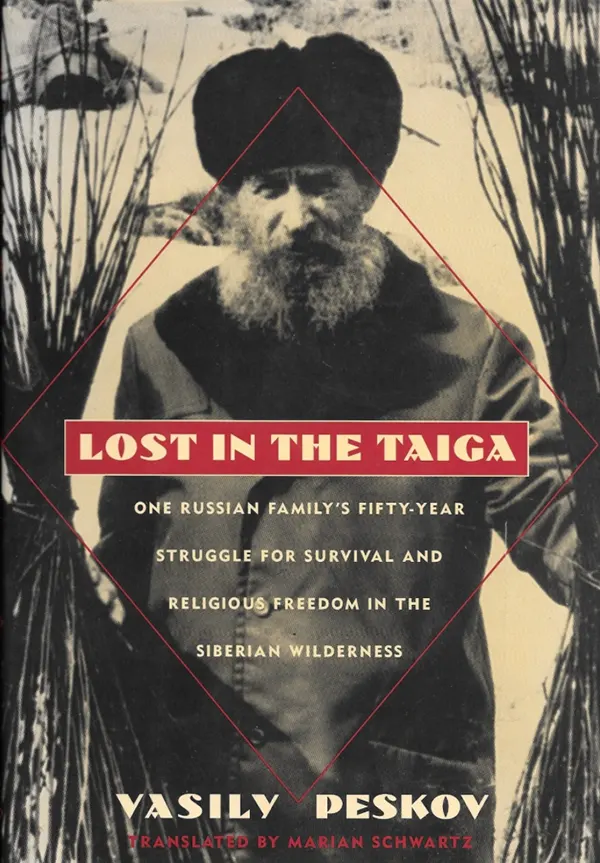

In the summer of 1978, a normal helicopter trip over the thick forests of southern Siberia led to one of the most amazing discoveries in contemporary Russian history.

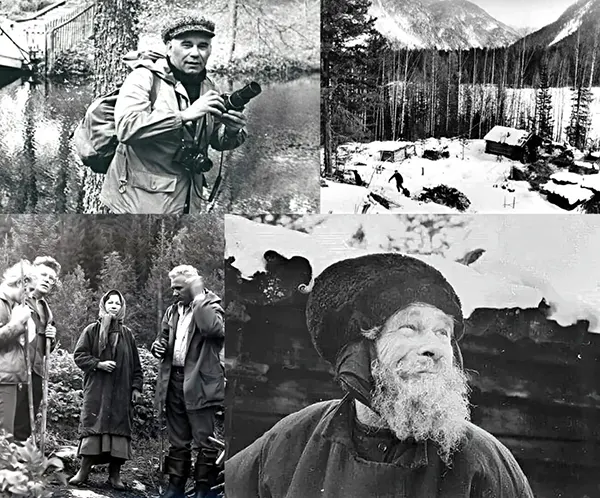

A pilot was checking out the rough terrain near the Mongolian border to find landing spots for a party of geologists when he saw something strange at the basin of the Abakan River: a small, hand-built structure hidden amid the trees.

It was a shocking sight. The region was more than 150 miles from the nearest civilization and was in a lonely part of the wilderness that was thought to be unoccupied.

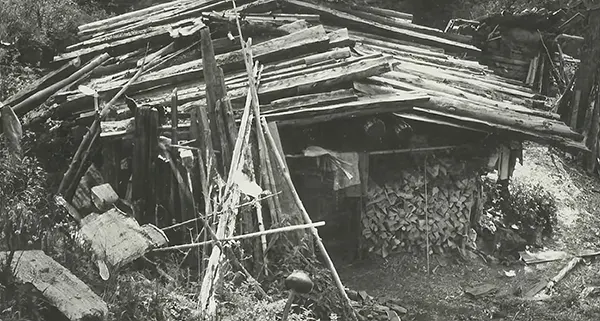

The land itself was wild and inhospitable, with thick forests, high mountains, and ice streams. But there it was, a single cabin standing despite all odds.

The geologists were interested and got the pilot to land nearby. They trekked for hours through thick taiga and up a steep mountain slope once they got to the ground, half-expecting the cottage to disappear as a trick of the light.

But the building seemed real, and there were evidence of life all around it, including a small garden with few crops and the sound of voices coming from inside.

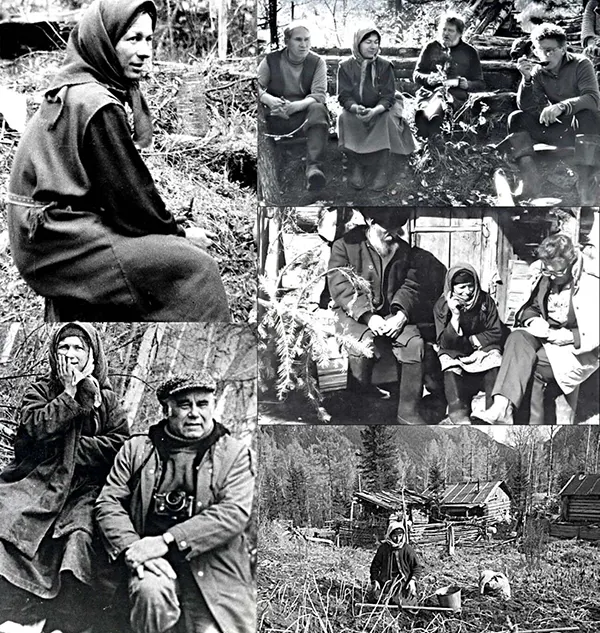

The hut was made of logs, dirt, and whatever else that could be found in the jungle. Inside, the air was heavy with the fragrance of decay and damp wood smoke.

A little fire blazed in one corner, casting flickering shadows over the soot-darkened walls. The floor was covered with potato peels and pine nut shells, signs of a hard life that was far from the comforts of life in the Soviet Union.

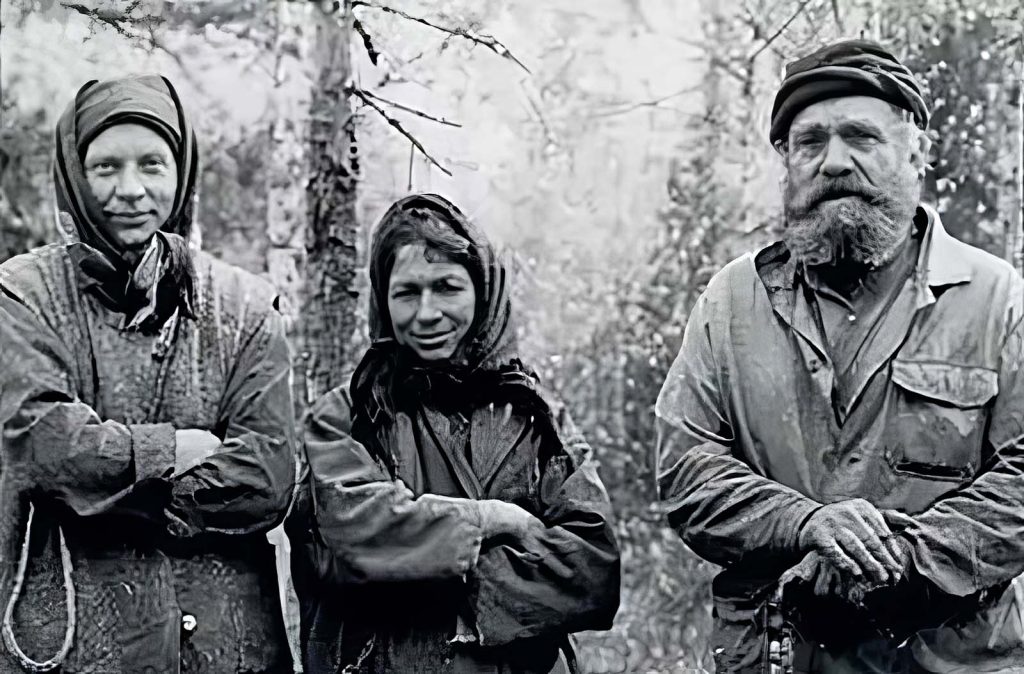

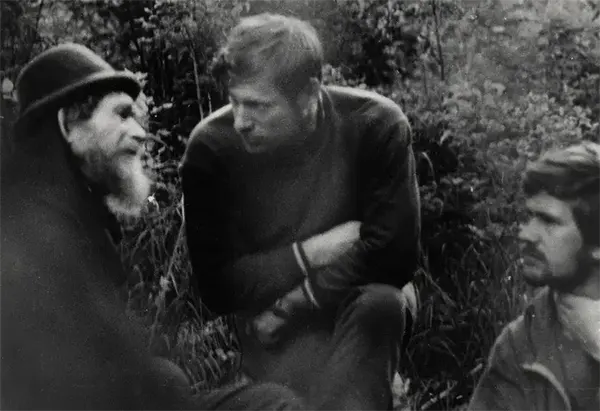

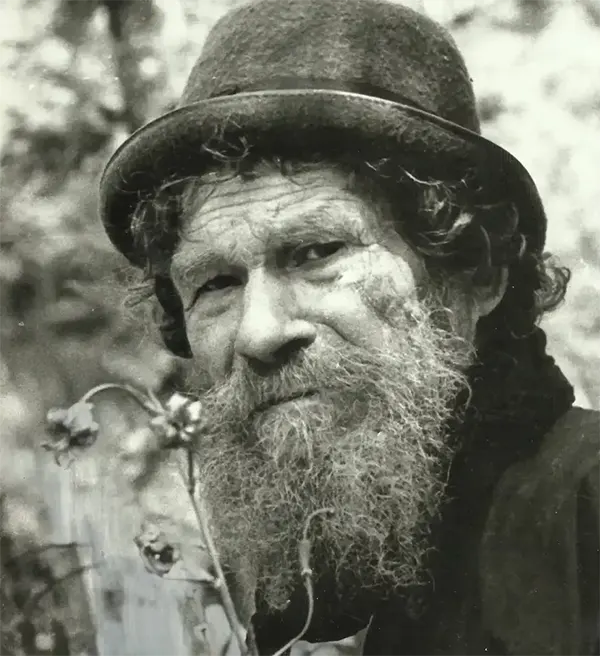

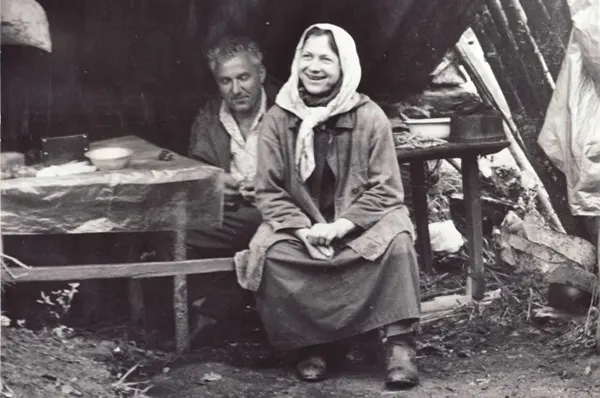

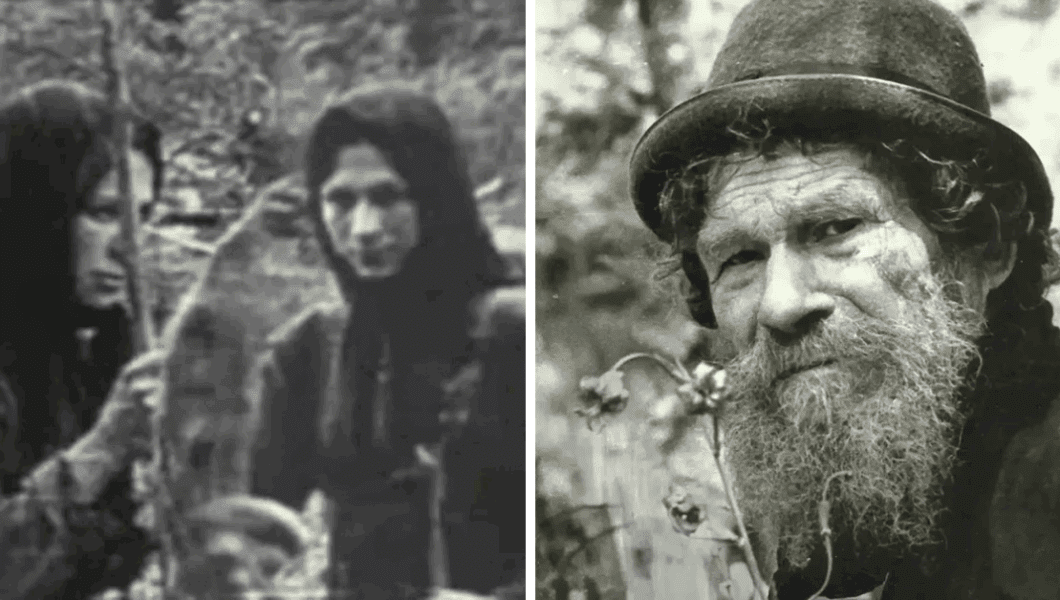

Five people came out of the shadows as the geologists looked about. A calm old man with a long gray beard walked up and remarked, “Well, since you’ve come this far, you might as well come in.” Karp Lykov was his name.

Karp introduced his four kids: Natalia, Dmitriy, Savin, and Agafia. They were emaciated, wore rags, and were wary of the guests.

A woman’s voice in the background trembled with prayer, saying that the strangers’ coming was punishment for their misdeeds. The scene was like being in a different century.

Karp looked willing to talk, but his kids stayed away. The women, in particular, looked scared and upset.

The geologists were careful about how their presence may effect the family and only visited them briefly and respectfully over the next few days.

Trust started to build over time. Karp started to talk about how his family ended up living alone and cut off from the outside world during one of these meetings.

It was a story formed by faith, fear, and the need to stay alive. It had started decades ago in a very different Russia.

Why the Lykovs Chose a Life of Complete Isolation

Long before that July day in 1978, the story of how the Lykov family disappeared into the Siberian forest began.

They didn’t just disappear by accident; they did it on purpose because of their faith, terror, and hunger for freedom.

The Lykovs were members of the Old Believers, a strict religious group that broke out from Russian Orthodoxy and has been against changes to the church’s rituals since the 17th century.

Since Peter the Great’s time, they had been persecuted in waves, with both the Russian state and the official church seeing them as heretics.

Many Old Believers had to hide in distant places for hundreds of years to keep their traditional traditions safe from the gaze of the authorities.

The pressure grew stronger after the Russian Revolution in 1917. The new Soviet government was even more hostile to religion, and many Old Believer communities moved to the outskirts of the Russian empire to avoid harassment and bloodshed.

The worst time was in the 1930s, during Stalin’s Great Purge, when it was not only perilous to be a Christian but also against the law. Worship was made illegal, churches were destroyed, and anyone who believed were arrested or killed.

At the time, Karp Lykov was a young man who saw this repression happen. One day, when he was working in the fields, he saw a Soviet patrol kill his brother in cold blood because of his religious views.

That one moment changed everything for him. Karp made a life-changing choice to run away since the threat was getting closer and there was no possibility of safety inside Soviet society.

Karp gathered what little he had in 1936: his wife Akulina, their nine-year-old son Savin, their two-year-old daughter Natalia, a few household things, and a few seeds.

They all went into the Siberian taiga together. What started as an escape developed into a life of exile.

Every year, the family moved farther into the woods, staying away from the outer world.

They erected temporary cabins along the route and slowly learned how to live off the land.

They finally made their home in a remote and scary place, more than 6,000 feet above sea level on a mountaintop near the Yerinat River in the Abakan River watershed.

The place was so far away that the closest town was 250 kilometers (approximately 160 miles) away.

A Life Carved Out of the Wilderness

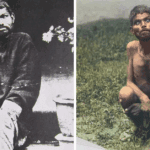

The Lykovs had to rely on the things around them to stay alive. They only carried a few metal pots and basic tools from the outside world.

They didn’t eat much. Their diet consisted largely of potatoes, rye, berries, and the occasional animal they were able to trap. Hunting was sparse, thus foraging became a daily need.

They made new clothes out of hemp and birch bark when their old ones wore out. These things didn’t shield them very well from the cold, but it was all they had.

Even their pots and pans started to break down over the years. Akulina was always creative. She made new containers out of bark and anything else she could find, but cooking was impossible without metal. The fire in their hut was merely there to keep them warm.

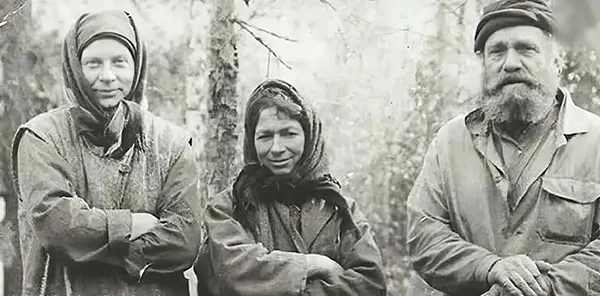

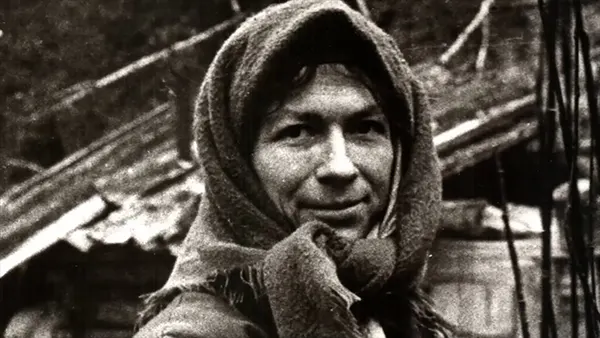

There were times of happiness even when things were hard. Dmitry and Agafia were born in the woods, wrapped in cloth that had been woven by hand and given little shoes made of bark.

Karp spent all of his time teaching his kids how to survive by showing them how to get clean water, cut firewood, and keep their fragile home safe from the weather.

But in 1961, something terrible happened. In June, an unexpected snowfall killed their crops, leaving the family with little food.

Their main food, potatoes, had frozen in the ground, and with winter coming, things didn’t look good. F

Akulina made a terrible choice since her children were in so much pain. She decided to go without food so they could live, and in the end, she gave her life for theirs.

The geologists were clearly upset when they found out she had died. They offered to take the family back to civilization, where they would find warm homes, medical attention, and food, but the Lykovs said no.

The kids didn’t know anything about the world outside. They had been taught that cities were sites of sin and pain, so the thought of leaving their home made them very uneasy.

The family didn’t know about World War II, the nuclear age, or the big changes that had happened in the world while they were away. For them, time had stopped.

The geologists did what the family wanted, but they left them with a few things they needed: salt, grain, knives, forks, paper, a torch, and pens.

Life After Discovery

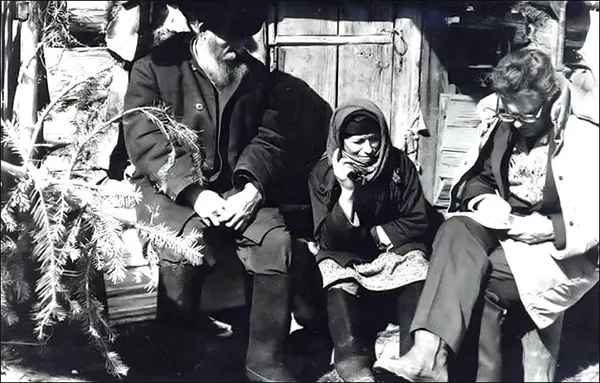

The geologists resumed their mission but made regular visits to the Lykovs, who had grown close to them.

Multiple invitations to relocate were extended, yet the family chose to remain in their earthen cabin, where temperatures often stayed near freezing.

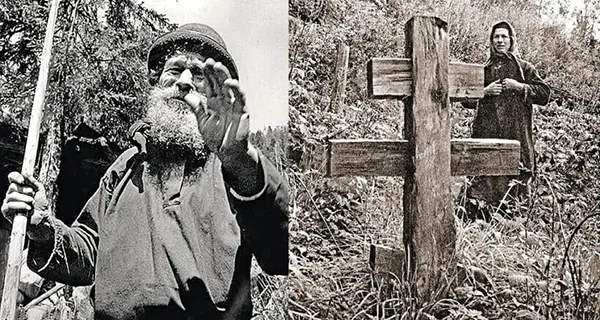

As mentioned above, in 1981, Savin, Natalia, and Dmitry passed away within days of each other. Karp and Agafia lived peacefully in the cabin until Karp died in 1988.

After her father died, Agafia stayed at the homestead and took care of the small plot and the goats. For 18 years, she lived in the hut with Yerofei Sedov, one of the geologists.

Agafia said VICE News in an interview that he didn’t help her and that she had to get water for him. On May 3, 2015, Sedov died.

That year, Georgy Danilov, a 53-year-old man from Orenburg, accepted Agafia’s public need for help and joined her. He moved to her isolated home and helped her when she needed it.

In 2016, Agafia was flown from her rural village to a hospital in Tashtagol because her legs were in so much pain after years of hard life.

She got help and then went back to the jungle, where she still lives as of 2024.

When asked what she felt about living in the city, Agafia said, “There are too many people and too many cars.”

(Photo credit: TASS / Wikimedia Commons / Yandex.ru / RHP).

No Comments